![]()

1

Cognitive

Neuropsychology

as a Science

We have our sandwiches on a hill outside Weston with a vast view over Somerset. She wants to say, ‘What a grand view’ but her words are going too. ‘Oh,’ she exclaims. ‘What a bit lot of About.’ There are sheep in the field. ‘I know what they are,’ she says, ‘but I don’t know what they are called,’ Thus Wittgenstein is routed by my mother.

Alan Bennett (Writing Home, 1994)

Cognitive neuropsychology is founded on the principle that one of the easiest ways to understand how a system works is to observe what happens when it goes wrong. By carefully recording and analysing the various errors that can occur in a system you can build up a picture of how its components are organized and how they operate. Before considering how this approach can be applied to the complex functions of the human brain consider how it might be applied to the relatively simple task of understanding how a television works. In an intact television you are not aware of the various components that contribute to the output. However, if you observed enough faulty televisions you might begin to develop ideas about how they work. You would, for example, notice that televisions can lose sound but not vision and vice versa. This is an important observation because it tells us that these two components are independent because they can each function when the other is not working. Another observation you might make is that the picture can lose its colour. However, the opposite observation, colour without picture, never occurs. This means that the systems governing picture generation and colour are not independent because one, the production of colour, seems critically dependent on the presence of picture. Nonetheless the continual observation of colour loss with a normal black and white picture suggests that the production of colour involves a separate component of the television.

The above example is based on the assumption that the observer has no prior knowledge of televisions or any other concepts that might help understanding of how the television works. In practice many observers would have both prior knowledge and intuitions about what to look for. Thus their observations would not be naïve but guided by various assumptions such as an existing knowledge about the separation of audio and visual channels and the fact that televisions have colour controls that enable the colours to be manipulated independent of picture quality. In short your observations of faulty televisions would be theory-driven in that you use pre-existing knowledge to both guide and interpret your observations.

The aim of cognitive neuropsychology is to provide a greater understanding of how the brain carries out mental operations based on the observation of people who have developed specific deficits as the result of brain damage. Cognitive neuropsychology is heavily dependent on careful observation of the behaviour exhibited by brain damaged people but it is also guided by the theoretical framework provided by cognitive psychology.

Cognitive Psychology and Modularity — A Very Brief Overview

Before 1960 the dominant approach to understanding human mental processes was provided by behaviourists such as Skinner. Behaviourism takes the view that behaviour cannot be explained by making any appeal to internal structures or processes within the brain. Instead behaviourists sought to account for all human behaviour in terms of the relations between inputs (stimuli) and outputs (responses). In 1959 the linguist Chomsky wrote a powerful critique of the behaviourist approach and, in essence, came to the conclusion that the nature of mental life could not be investigated effectively without some theory about how the structures and processes of the brain were organized and the principles by which they operated (Chomsky, 1959).

Experimental psychologists face a challenge encountered in no other science except perhaps sub-atomic physics. There is little disagreement that mental processes take place in the brain and, from microscopic examination, we can see that the brain comprises nerve cells and fibres which interact with one another within a complex network. However, knowing that the mental processes that we seek to understand are a product of the interaction between nerve cells does not help us comprehend how mental processes take place. In short the explanation of psychological processes cannot, at present, be reduced to an understanding of how the brain works at a physiological level. Because of this psychologists are forced to use analogy or metaphor in explanation; that is they attempt to explain the workings of the mind in terms of something else that we do understand.

Cognitive psychology can be defined as the branch of psychology which attempts to provide a scientific explanation of how the brain carries out complex mental functions such as vision, memory, language and thinking. Cognitive psychology arose at a time when computers were beginning to make a major impact on science and it was perhaps natural that cognitive psychologists should draw an analogy between computers and the human brain. The computer analogy was used frequently to draw up a model of the brain in which mental activity was characterized in terms of the flow of information between different stores.

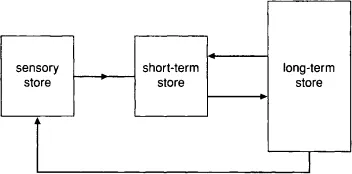

Perhaps the most well known of these models was the model of memory put forward by Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968). In this model (see figure 1.1) the human memory system comprises three stores: New information (external stimulation) first enters sensory store where, after initial processing it passes to short-term store. While in the short-term store information can be actively processed guided by the intentions of the individual. Thus new information can be stored in the permanent repository of memory known as long-term store or be discarded. The system also needs to be able to retrieve stored information at a later date and for this reason the model embodies a two-way flow of information between short- and long-term store. The interaction envisaged between short- and long-term store very much resembles the interactions that occur between the central processing unit of a computer and its permanent database. It is important to stress that the computer analogy attempted to emphasise the similarity between the organization of the human mind and that of a computer. It was evident from the outset that the precise manner in which computers operated, that is the binary coding system employed, was not an appropriate basis for understanding cognitive processes themselves.

The computer analogy, in modified form, continued to dominate cognitive psychology for the next 20 years. A vast range of models were produced each attempting to explain some form of mental activity in terms of a series of processing stages intervening between an input and an output. Despite their widespread use, information processing accounts of mental abilities have not been without criticism. Indeed this approach has been characterized by some commentators as nothing more than ‘boxology’ — defined by Stuart Sutherland as ‘The construction and ostentatious display of meaningless flow charts by psychologists as a substitute for thought’ (Sutherland, 1989, p. 58). These criticisms arose because cognitive psychologists became increasingly happy to specify mental processes in terms of information processing systems without offering any explanation of how any of the supposed stages worked.

Figure 1.1 The multistore model of memory.

Modularity

More recently the cognitive approach has been strongly influenced by the concept of modularity. This has gone some way to addressing the accusation of boxology because properties are assigned to the processing elements, or modules, that comprise any system. The term modularity derives from computer programming and refers to the principle that it is important to make the different components of the program as independent from one another as possible. Modularity will then make any debugging operations much easier to carry out because the nature of the fault will tend to be an accurate indicator of which program module is at fault. An important feature of a modular system, therefore, is that the components are autonomous in that they remain functionally intact when other components of the same system become corrupted.

Marr (1976) proposed that the brain might also have a modular organization because modularity imparts considerable advantage to any complex system that is attempting to evolve. The reason for this is that a modular system is easier to correct or improve because changes can be made to specific parts of a system without the need for parallel changes elsewhere. In vision, for example, improvements might occur in modules concerned with extracting information about depth without the need to improve the modules integrating the resulting depth information into the final percept.

The idea of modularity has been extensively developed by Fodor (1983) in his book The Modularity of Mind. Fodor’s major contribution was to specify a number of properties that he assumed modules had.

1 Informational encapsulation: Modules carry out their operations in isolation from what is going on elsewhere. These operations are not amenable to ‘cognitive penetration’. Fodor illustrates this by pointing out that we are unable to overcome visual illusions even though we know full well that they are illusions.

2 Domain specificity: Each module can only process one type of input. Modules therefore deal in only one source of information.

3 Mandatory: Each module operates in an all-or-none fashion. Once activated it will carry out the entire processing operation for which it is responsible.

4 Innate: The modules of the cognitive system are innate and not acquired through development. This is a highly controversial claim which we can highlight by considering this statement from the neurologist Geschwind:

the overwhelming majority of humans who have ever lived have been illiterate, and even today I believe it is the case that a very large percentage … of the world’s population have never had the opportunity to learn to read. Most of us come from families that four generations ago did not possess the ability to read

We can interpret the above fact in two basic ways. First we could argue that the short history of reading in humans means that reading is carried out by modules that pre-existed to carry out other functions. Support for this view can be found in the study of developmental dyslexia where it can be found that dyslexia often occurs in association with deficits in more basic abilities such as sequencing and left-right discrimination. Alternatively we could argue that the innate assumption is wrong and that new modules can evolve within a developing brain. Arguments supporting this view would be the existence of highly specific acquired dyslexias in which the process of reading seems selectively disrupted (see below and chapter 7).

For our present purpose it is fortunate that the two aspects of modularity most important to cognitive neuropsychology, information encapsulation and domain specificity, are the least controversial. It is important to note, however, that Fodor’s definition of modules is not strictly adhered to within cognitive neuropsychology in that modules are often defined as accepting different types of input whereas Fodor considers modules to be input-specific.

Identifying modules cannot, however, be the only goal of cognitive psychology. For a proper explanation we also need to understand how the processes operating within hypothesized modules are carried out. Fodor’s view in this area is highly controversial. He accepts that some scientific explanation of how modules operate can be achieved. However, only more basic cognitive processes are held to be modularized and more complex processes such as thinking and deciding are thought to be highly interactive with one another. For Fodor this level of interactivity precludes effective scientific investigation because it is not possible to offer any precise theory about how more complex activities might be carried out.

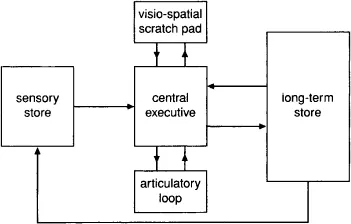

In general cognitive psychology has not gone along with Fodor’s viewpoint and theories abound to explain all manner of human cognitive processes. A good example of a cognitive model embodying both modular and non-modular components is the working memory model of Baddeley and Hitch (Baddeley and Hitch, 1977; Baddeley, 1990). This model is a development of Atkinson and Shiffrin’s concept of short-term store (see figure 1.2). It comprises a central executive and two auxiliary components, an articulatory loop and a visuo-spatial scratch pad. The central executive represents the locus of control of the cognitive system. It is responsible for determining how inputs should be dealt with and for retrieving information from long-term storage. It is also multimodal and not domain-specific, able to combine information from both different sensory modalities and different types of stimulus input.

In contrast the two auxiliary components have very much the character of modules. The articulatory loop is considered a limited capacity system specifically dedicated to the processing of phonological information. Similarly the visuo-spatial scratch pad is solely dedicated to the representation of a limited amount of information in terms of its visuo-spatial characteristics. Working memory is just one example of a large number of models that currently exist to explain human cognition at various levels of complexity. The scale of this enterprise is too vast to even attempt a summary here. Instead the reader will have to be content in knowing that relevant theories will be explained at appropriate points in the text.

Figure 1.2 The multistore model of memory revised to incorporate the concept of working memory.

Parallel Distributed Processing

Most recently the study of cognitive processes has undergone an almost revolutionary change with the advent of parallel distributed processing (PDP) or, as it is more often known, connectionism (McClelland and Rumelhart, 1986). PDP models are implemented as computer programs known as networks. Unlike the models we have considered so far, in which each component of the model is explicitly stated (e.g. central executive, articulatory loop), connectionist models learn by themselves and set up their own representation of any given set of information.

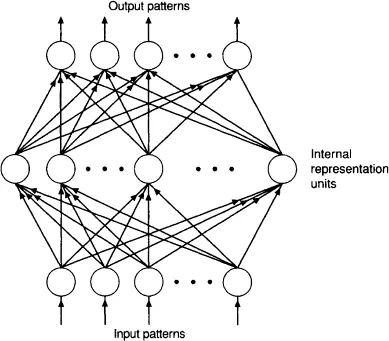

A network comprises a series of nodes or units linked to each other by connections which can be either inhibitory or excitatory in nature. In addition the strength of any connection can be modified by assigning a particular weight. It is an important feature of these models that information about any concept is distributed across many nodes and not the property of a single node. Different pieces of information thus correspond to different patterns of activity within the same network (see figure 1.3).

PDP networks are able to learn by using rules or algorithms to change interconnections between the nodes of the network. One method of learning is the back-propagation algorithm which is a means of making an output conform to a desired state. For any input, the system is informed about what the resulting output should be. This information is compared with the actual state of the network when the stimulus is present and an adjustment is made. This process is incremental and networks need many exposures to a stimulus before they learn the correct output. Methods like back propagation allow a network to represent information. But because human learning is not characterized by having pre-existing knowledge of the desired outcome, algorithms like back-propagation have obvious limitations. However, proponents of PDP models argue that it is the properties of the established network that are of interest to psychologists rather than the manner in which they become established.

Figure 1.3 A prototype connectionist network comprising a layer of input units, a layer of interna...