eBook - ePub

Limits to Privatization

How to Avoid Too Much of a Good Thing - A Report to the Club of Rome

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Limits to Privatization

How to Avoid Too Much of a Good Thing - A Report to the Club of Rome

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Limits to Privatization is the first thorough audit of privatizations from around the world. It outlines the historical emergence of globalization and liberalization, and from analyses of over 50 case studies of best- and worst-case experiences of privatization, it provides guidance for policy and action that will restore and maintain the right balance between the powers and responsibilities of the state, the private sector and the increasingly important role of civil society.

The result is a book of major importance that challenges one of the orthodoxies of our day and provides a benchmark for future debate.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Limits to Privatization by Marianne Beishem,Oran R Young,Ernst Ulrich von Weizsacker,Matthias Finger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

Introduction

Limits to Privatization

Seeking a Balance

Beware of extremes! What is needed is a proper balance: between freedom and order, between innovation and continuity, and – the topic of this book – between the private sector and the public domain.

Different actors will have their own preferences about the best balance between each pair of extremes. Poorer people may favour more order and a bigger public domain, while affluent people may want more freedom and more private ownership. Many believe private ownership promotes efficiency and wealth creation. Yet, even affluent countries committed to the productive value of private ownership seek a balance between the private sector and the public domain, regardless of the tone of the rhetoric they employ.

Striking a good balance between private and public is the theme of this book. Thus, we address one of the great issues of our times. Which services, including health, education and welfare systems, as well as law enforcement, infrastructure and finance, can be entrusted safely to the private sector? Are there good reasons to keep a sizeable proportion of a society’s land and natural resources within the public domain? Under what circumstances is it better for the state to own and operate (some of) the means of production? Where functions are performed by private companies, what sorts of rules and regulations should govern them?

There are no simple answers to these questions. Yet, some important observations about recent developments are coming into focus. The thesis we develop in this book is that the recent and continuing swing towards privatization is in danger of becoming too much of a good thing. It may carry us beyond reasonable limits and produce undesirable consequences that outweigh the undeniable benefits of many forms of privatization.

In this book we describe and explore privatization in a range of sectors. Thousands of cases exist worldwide. Some have been successful by any reasonable standard, but others have failed. We have collected and selected, to the best of our ability, examples from around the world and from all relevant sectors.

What goes wrong attracts the attention of the media much more than what goes well. Never mind. It is widely assumed that privatization is a good thing; there is more need to understand its limitations and hazards than to confirm the assumptions underlying the trend.

At the time when our plans emerged to write this book, in 2001, we knew of no systematic worldwide study of privatization across all sectors. In the meantime, the World Bank has published a highly useful assessment of privatization of infrastructure in developing and Eastern European countries (Kessides, 2004). This policy research report is unusually candid about failures, although it maintains the Bank’s general assertion that privatization enhances efficiency, enlarges access to essential services and helps solve many development problems.

Before assessing actual experience through a series of short case studies and snapshots, we need to flesh out what we mean when speaking of limits to privatization and suggest strategies for rectifying the growing imbalance that has emerged in this realm. The following sections of this introductory chapter set the stage for our investigation.

A Word on Definitions

Like most prominent policy concepts, ‘privatization’ has a cluster of overlapping meanings. In this book, we use the term in its widest sense to refer to all initiatives designed to increase the role of private enterprises in using society’s resources and producing goods and services by reducing or restricting the roles that governments or public authorities play in such matters. This is often carried out by a transfer of property or property rights, partial or total, from public to private ownership. But it can also be done by arranging for governments to purchase goods and services from private suppliers or by turning over the use or financing of assets or delivery of services to private actors through licences, permits, franchises, leases or concession contracts, even when ownership remains legally in public hands. There are even cases such as ‘build-operate-transfer’ contracts, where the private sector creates an asset, operates it for a certain length of time, and then transfers it into public ownership. Where necessary, we use more technical definitions in accordance with the relevant literature.

Privatization is not the same as deregulation, which means the removal or attenuation of restrictions, including requirements and prohibitions, imposed by a public authority on the actions of public or private actors or, in essence, any reduction of state control over the activities of societal actors. Privatization often comes with deregulation, and especially the removal of exclusive rights and the opening-up of a service to competition. But either can occur without the other. A major theme running through the book is that the success or failure of privatization is often strongly influenced by the kind and degree of regulation accompanying it.

We draw a distinction, as well, between privatization/deregulation and liberalization, which means actions by governments to stimulate competition among companies in markets. Liberalization can take a variety of forms, ranging from anti-trust measures to the elimination of subsidies and the introduction of incentives to stimulate competition between private actors. Although they are separate phenomena, privatization/deregulation and liberalization often go together. In this book, we focus on privatization/ deregulation, referring to liberalization as it affects privatization.

Changing Role of the State

Throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries, governments assumed responsibility for an ever-expanding range of societal functions, in particular social and health functions. Later during the 19th century, but especially in the beginning of the 20th century, governments also played a crucial role in supplying infrastructure, such as highways, airports, port facilities, telecommunication and postal services, water supply and reservoirs, sewerage and irrigation systems, hospitals, schools, and, increasingly, in maintaining these facilities. Some infrastructure was actually built and initially owned by private entrepreneurs and later nationalized, notably many railways, power grids and telecommunication networks.

Nationalization was one of the central programmatic ideas of communism from the days of the Russian revolution onward. After World War II, communism spread further, and state-owned infrastructure and industries became the normal state of affairs throughout the communist bloc. But nationalization took place also in many Western countries, as well, notably in Europe and Latin America. Ideology (often socialist rather than communist) played a part. But nationalization was often motivated by pragmatic assessments that capital could be raised more readily and cheaply by the state, or services delivered in a more efficient, coordinated and effective way, if managed in the public interest as coherent and integrated systems rather than left to a patchwork of private companies who would inevitably put their individual commercial interests first. It is sobering to note how similar these arguments for nationalization – accessing investment, service responsiveness and efficiency – are to some of those advanced 30 to 40 years later to justify privatizing the same services.

States emerging from colonial rule during the 1960s and 1970s saw ownership and responsibility for essential infrastructure as the most natural task of the state. By the end of the 1970s most of the world’s governments had assumed far-reaching responsibilities for their infrastructure and various means of production.

During recent decades, however, the tide has begun to flow in the opposite direction. Since the 1980s, preceded by economic theory generated in the 1960s but significantly pushed by globalization, technological developments, market expansion and the growth of private operators, a new trend has emerged of questioning the state’s dominant role and of strengthening the private sector. This trend has manifested itself mainly in the privatization of an array of activities previously included in the public domain, together with deregulation in the form of opening previously protected industries to competition and of reducing restrictions on the activities of private enterprises.

During the 1960s, the spirit of privatization went against established cycles of change and took on an air of courageous endeavour. Economists such as Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ronald Coase paved the way.1 They treated the then fashionable search for social equity as inefficient, partly dishonest and demoralizing for high achievers and thus, in the end, counterproductive to its own aims.

Neo-conservative politicians embraced their ideas as a basis for attacking affirmative action and other equity measures in the US, the UK and elsewhere. Socialist and equity concerns were seen as a form of romanticism or a coverup for state cronyism, if not as a dangerous ideological support for the arch enemy, the Soviet Union.

In political battles to promote the emerging neo-liberal and neo-conservative paradigms, the most widely used term was ‘economic efficiency’. The efficiency code was used successfully to delegitimate ‘inefficient’ state functions in an ever-growing array of sectors. The ideological adversary at the time was Keynesianism. Neo-conservatives said that Keynesian deficit spending was only leading to or deepening ‘stagflation’, the unpleasant combination of high inflation rates and high unemployment that was characteristic of the late 1970s (see, for example, Bruno and Sachs, 1985). A lean and efficient state, by contrast, would promote tax reductions, low inflation and better services – and that from the private sector. The enlarged private sector, not the state, would take care of economic growth and technological progress. In retrospect, nobody would seriously deny that the paradigm shift has been successful by its own standards of efficiency.

But can we afford to assume that these arguments will hold for all cases? Or are their limits to privatization in the sense of thresholds beyond which the costs of privatization outweigh the benefits?

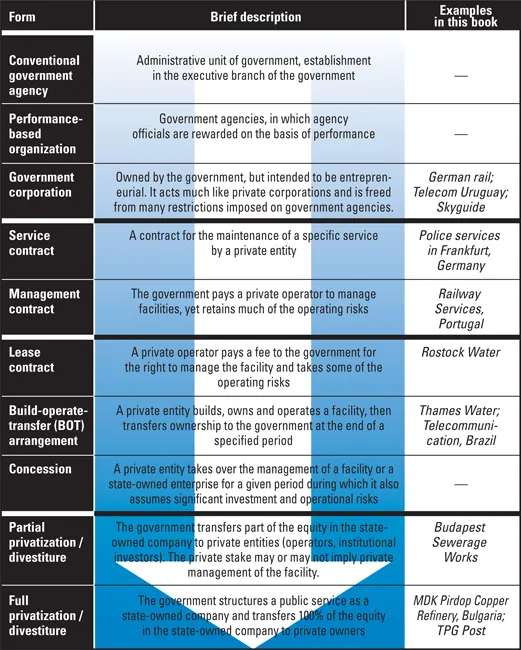

Forms of Privatization

In this book, we devote particular attention to four broad categories of privatization, ranking from ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ privatization:

- putting state monopolies into competition with private or other public operators;

- outsourcing, in which governments pay private actors to provide public goods and services;

- private financing in exchange for delegated management arrangements, often with a view to transferring ownership to the state after a period of profitable use; and

- transfers of publicly owned assets into private hands.

The first category includes cases in which governments alter the rules of the game to allow private enterprises to engage in specific activities. This might result in competition between private and public operators. In order to match private-sector efficiency, the public operator often takes efficiency as a measure of performance. Examples for this category include the granting of permission for private airlines to compete with national airlines, the authorization of private universities and hospitals and the deregulation of the electricity market.

Figure 1

The public–private continuum. Different possible service delivery models from fully public to fully private with some illustrations.

The second category includes all those cases in which governments contract with private enterprises to supply specified goods and services previously provided by public agencies. Arrangements of this kind have a long history, going back, in the case of France, to the late 19th century. But recent decades have witnessed an explosion of new arrangements of this sort, dealing with services ranging from education through healthcare, public transportation, security systems and on to prisons.

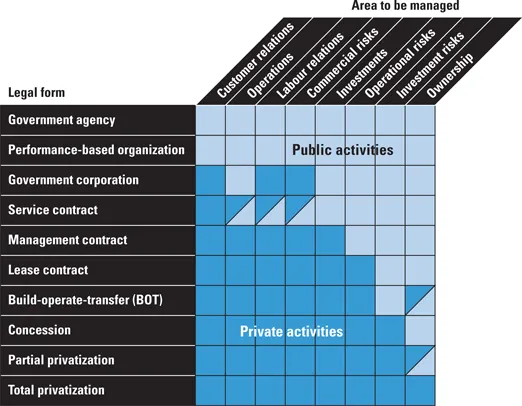

Figure 2

Schematic overview illustrating different mixes of public and private activities. Government activites are light shaded, private activities dark.

The third category involves the financing of infrastructure but, increasingly, also other projects (e.g. schools, hospitals and museums) by the private sector. These include build-operate-transfer (BOT) arrangements, concessions and lease contracts. The World Bank has been especially active in developing sophisticated models where the private sector provides the money in exchange for various forms of delegated management arrangements so that the investments can be paid back. Originally only practised in developing countries, this approach to financing public investments is increasingly common in industrialized countries...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Boxes

- Foreword by the President of the Club of Rome

- Preface

- Editors’ Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: Privatization In Many Sectors: Case Studies And Snapshots

- Part 3: Privatization In Context

- Part 4: Governance Of Privatization

- Part 5: Conclusion

- About the Editors and Authors

- Notes

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- References

- Index