![]()

![]()

As we have no immediate experience of what other men feel, we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation.”

(Adam Smith, 1790, p. 4)

The entire book uses a conceptual approach to InterCultural Business Negotiations (ICBN) based on the Deal and/or Relationship model which serves as a guiding framework, essentially because nations and cultures do not make the same use of these two key aspects of negotiation, do not value them similarly, and do not order them in the same manner. Priority and assumed causality are the central issues in explaining Deal-Making versus, or, and/or Relationship-Building framework.1

The introductory chapter explains and illustrates the main dimensions of the Deal and/or Relationship model of ICBN. It does so by starting from definitions of business negotiation, highlighting the origin of knowledge about negotiation, and showing that there is a strong Western bias (e.g., the deal is of paramount importance and the relationship is a non-necessary by-product, in fact a non-pivotal issue). Because Deal and Relationship tend to intermingle and interact in complex manners, I highlight how they are likely to combine in ICBN settings. Deal-Making corresponds to an ideal-type (IT) of calculative rationality (IT1) while Relationship-Building corresponds to relational rationality (IT2).2 In IT1, deals come first and relationship may (or may not) follow. IT1 is interest-centred and to a certain extent rights-centred. In IT2, the relationship comes first and deals are the (supposedly) natural consequence of good relationships.3 This chapter first defines negotiation and discusses the predominantly U.S. (IT1) origin of knowledge about negotiation. It further presents the Deal and/or Relationship paradigm and examines key negotiation concepts in the light of this paradigm. The last section explains how this book is organized.

Negotiation defined

Let us start with an example, that of negotiations between airlines and aircraft manufacturers (the same holds true if you add aircraft engine manufacturers, a triangle of relationships). They have regular deals (e.g., buying or leasing aeroplanes) over long periods of time. Each time they negotiate a particular contract, they maintain or develop relationships since the airline will keep the planes for many years and will often tend to be loyal to a particular aircraft manufacturer (e.g., Boeing and British Airways). Whether deals are more important than relationships, whether deals can be closed without a relationship (in an either/or perspective), whether the deal or the relationship should be prioritized, and how deal and relationship combine in ICBN (in an either/and perspective) are the topics of this book.

The scope of business negotiation is quite large, virtually infinite: including sales contracts, business deals, agency contracts, company takeovers, mergers and acquisitions (M&As), joint ventures, and individual as well as collective agreements between employers and employees (i.e., industrial relations). In many countries, there is some leeway for large taxpayers in negotiating with taxation authorities. Similarly, lobbying implies negotiating business regulations with public authorities. Beyond signing contracts, when conflicts arise from implementation, litigation and out-of-court settlements appear as extended negotiation activities.

A general definition of negotiation

Negotiation generally is a face-to-face activity with two or more players who, facing interest divergence and feeling that they are interdependent, choose to actually look for an arrangement (deal) to put an end to this divergence and thus create, maintain, or develop a relationship. Let us go through the individual elements of this definition one by one.4 Negotiation is first and foremost an activity with start and end dates involving joint task(s) and a doing orientation. Not all human activities involve negotiation. Communication per se is not negotiation. Individuals and organizations do not constantly negotiate. Negotiation, being bilateral or multilateral by nature, takes place between two or more players. The parties share a sense of being interdependent, which involves objective (e.g., shared interests and mutual dependence) as well as subjective (i.e., perceived) dependencies on both sides. These dependencies are neither necessarily symmetrical nor balanced. Conflict, which involves the ways in which parties “play” their interest divergence, can be increased, but also mitigated by interdependence. The parties choose to provisionally put aside the interest divergence they face, that is, downplay conflict, so as to actually (effectively) look for an arrangement. The adverb “effectively” implies that, in some negotiations, a party may not really look for an agreement, but rather try to obtain proprietary information through data gathered during the negotiation process without being willing to close a deal, which would force it to pay for the other party’s knowledge.5

The next point (“and thus…”) misleadingly seems a consequence of the previous deal-related sequence. “Creating, maintaining or developing a relationship between the negotiating parties”, although frequent, are not necessary sequels of the deal. Rather than an unmanaged and somewhat unintended consequence of Deal-Making, Relationship-Building may be a condition, a necessary antecedent of Deal-Making. This is a major divide in terms of cross-cultural/intercultural business negotiation. Certain cultures are deal-prone and find it normal to search for a one-shot contract, a discrete transaction with no future. In other cultures, the relational emphasis is much stronger: negotiation has a lot to do with developing a long-term partnership, which is assumed to be an asset if difficulties arise when implementing deals negotiated within the relational frame (e.g., in the oil business, between drilling operators and oil companies).

Alternative functional definitions of negotiation

Negotiation can first be seen as a resource allocation activity. This leads to emphasis on its deal-oriented bargaining side, in a mere calculative and single issue setting (i.e., exchanging cash against an item), evident in trade and economic exchange (a lot of single-issue, one-shot bargaining takes place in a relational vacuum). Examples are buying second-hand cars, souk bargaining, or haggling. Second, negotiation is often related to the search for solutions (e.g., creating a common venture, dividing joint outcomes, designing joint rules that will solve a number of recurrent conflicts). This problem-solving orientation, which is still deal-oriented albeit much more relational, is fundamentally related to the objective of increasing joint utility: there are many alternatives available and, among these, one or possibly two options are the best. However, a party that is sincerely engaged in problem-solving may at times reveal information that will be used by the other party to increase its share of the pie. The third functional definition of negotiation, more relational and also quite meaningful, emphasizes its nature as a collective decision-making method in situations in which there are no rules and/or hierarchy. The scope of negotiation increases as and when rules and hierarchy play a diminishing role. In a traditional society in which hierarchical relationships dominate there is less room for negotiation, which is a basically horizontal type of interaction between peers. If a society were organized along detailed, imperative, and impersonal rules, there would be no place for negotiation. However, since most rules require regular updates, exceptions, and adjustments, drafting joint rules (institutionalization) is a frequent negotiation activity. Common rules in an intercultural setting are understandably more difficult to design and to mutually comply with than intraculturally.6

The negotiation system

The negotiation system is a combination of relational dynamics, information exchange, persuasion, and bargaining processes which result in drafting agreements with joint as well as individual outcomes (for each party). In an international setting, relational dynamics are very likely to be culturally and linguistically coded because they are based on communication, communication styles, conflict resolution, information exchange, persuasion, and consensus building, and therefore differ both cross-nationally and cross-culturally. That is why several chapters are dedicated to these issues (especially Chapters 3, 4, and 5). Similarly, negotiation processes and strategies tend to display inter-national/-cultural variance (Chapter 7 and 8).

Bargaining versus negotiation

Bargaining is sometimes used as a synonym of negotiating and is also considered a subset of negotiation situations centring on price vs. object. However, in the toughest case a definition of bargaining would border on haggling, a single issue negotiation, one shot, with relational rituals rather than true relationships. Khuri (1968, p. 701) describes the rituals involved in bargaining in the Middle East. Bargaining always begins with standard signs of respect, affection, common interest, and trust. The seller’s speech evokes affection and creates an impression of friendliness and fraternity. As soon as the potential buyer shows interest in an item and asks for information, the seller replies:

Nothing in this (IT2) speech should be taken literally. The opening incantation is a way of expressing a social bond of mutual interest and trust through allusions to a probable family tie in a metaphorical sense. Relationships in fact, may be fake, simulated, and forged rather than real. Westerners sometimes feel guilty when walking away after bargaining with a souk vendor for half an hour without making any deal, with the impression that they are responsible for the seller’s wasted time and efforts. The souk vendor may simulate anger and possibly shout at naive buyers in the hope that increased feelings of guilt will make them come back. In general, it is the exact opposite that occurs. The buyer never comes back. This example suggests how culturally coded and sensitive relational processes are.

Bargaining deserves a special note. In many “developed/industrial” countries, there has been a strong decline in traditional bargaining activities. This largely relates to the compulsory display of price tags imposed by regulation and to the generalized practice of self-service in retail stores. Even though bargaining exists for equipment goods and for some large ticket items in consumer durables, a significant part of the world population (including many readers of this book) are not exposed to the daily rituals of exchange price exploration. Bargaining in souks or bazaars is good hands-on training for business negotiation. People from countries where bargaining is legally forbidden may be at a disadvantage because of their lack of practical experience.

Bargaining and reservation price

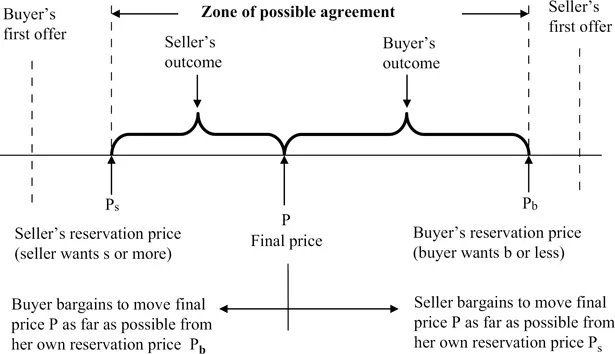

In Figure 1.1, we imagine a situation where a buyer and a seller face each other with the hope of agreeing on a price. They both have a reservation price (assuming that they have prepared before entering into negotiation), that is, the price below/above which they are not willing to sell/buy. Naturally, neither of them, if rational, is willing to reveal their reservation price, which remains purely private information. Thus their first offer will be under (buyer) or above (seller) their reservation price. In the Figure 1.1 the range between buyer and seller reservation prices defines a zone of possible agreement (often clipped into ZOPA). If the ZOPA is negative (the buyer’s reservation price is superior to that of the seller), they should walk away and not reach an agreement. Within the agreement zone, negotiation talent (among other factors) will decide how surplus is shared between both bargainers.

The negotiation setting

C...