This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The number of internally displaced people far outnumbers estimated refugees who have fled their countries. The majority of displaced populations survive with very little security or legal protection. Responding to the needs of internally displaced people is one of the greatest humanitarian challenges of our time.;Revised and updated from the first edition, this volume includes information on internal displacement in 47 different countries across the globe - that is to say all countries experiencing conflict-induced displacement at the time of publication. There is discussion of the causes of displacement, patterns of flight, protection concerns and international response.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Internally Displaced People by Janie Hampton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part 1

Issues and perspectives

1

Introduction

For every person internally displaced by conflict, there is a story – 25 million different stories of fear, persecution and human suffering. Each year, hundreds of thousands of people in different corners of the world are forced from the safety of their homes and compelled to take flight. Across regions and continents, direct threats to personal security and other forms of violence oblige individuals, families and entire communities to gather what they can of their belongings – if any – and depart for uncertain destinations.

Some of these people are able to take shelter with family or friends. Others congregate in camps where they hope to find safety, food and shelter. Still others hide in forests, jungles and other inhospitable terrain, too fearful to seek assistance of any kind. The journey is often difficult and dangerous. An untold number of people are victims of violence and disease along the way.

In some cases, people move to a neighbouring village for a short period until the fighting that caused their displacement has subsided. In still other cases, chronic or large-scale insecurity compels people to make a more dramatic and permanent move, to a camp at some distance from their home or to the outskirts of a metropolitan centre. In a good many situations, however, the movement is repeated with people displaced more than once and forced to flee to a range of different localities. In some of the worst cases, people are simply dispersed, fleeing without a trace and left to fend for themselves.

The Problem of Internal Displacement

The focus of this survey is on people who take flight within the boundaries of their home countries and are, thus, identified as internally displaced people, or IDPs. These people are forced to seek safety not through asylum in a second state, but before their own governments and within the confines of national borders. The welfare of internally displaced populations has become the subject of international attention because the governments legally accountable for their care and protection are often unable or even unwilling to act on their behalf. Indeed, in many cases, the government in question is at least partly if not wholly responsible for the displacement of its citizens in the first place. Internal displacement has also become an issue of increasing international concern because the mass displacement of populations can pose serious threats to the security and stability of entire regions.

The phenomenon of internal displacement has been widely described by international observers as one of the most pressing humanitarian challenges of our time. Since the end of the Cold War, conflicts between different communities, ethnicities, religions and socioeconomic groups have multiplied at an alarming rate. Intra-state conflicts have centred on secessionist demands or appeals for regional autonomy, on the persecution of groups on the basis of their ethnic, religious or socio-economic backgrounds, and on struggles over territories and the exclusive control of natural resources. A single conflict in one part of a country has often fragmented, leading to the emergence of still further communal disputes in other geographical areas of the state. At the same time, external support for one or more parties to the conflict remains a common feature of modern-day conflict, functioning to enlarge and sustain the vast majority of contemporary civil wars.

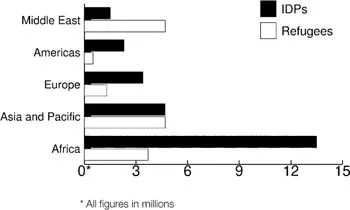

In the first part of 2002, about 25 million people were estimated to be internally displaced, up from an estimated five million in the 1970s (Schmeidl, 1998, p28).1 Today, IDPs outnumber refugees by nearly two to one, with a particularly large number of them – an astonishing 13.5 million – on the African continent. Sudan, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) currently host IDP populations in the millions. Uganda, Nigeria, Burundi and Somalia have either surpassed or are nearly reaching the half million mark.

Shocking figures of conflict-induced IDPs, however, are not limited to Africa. Across the globe, different country situations give reason for alarm. From Colombia to Indonesia, Turkey to Afghanistan, IDP statistics are in the millions. Add those countries where over half a million people remain internally displaced by conflict, and Iraq, Azerbaijan, Sri Lanka, Burma and India join the list.

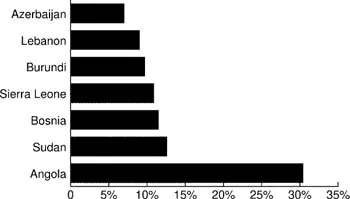

Although stark figures help to gain a general understanding of the scale of the problem in a particular country or region, they certainly do not tell the whole story. In countries such as Burundi or Lebanon, for example, where IDP numbers do not reach the millions, the ratio of the displaced to the national population is still quite high, nearly 10 per cent in each of these cases. These kind of statistics offer an indication of the limited capacity of host governments and resident populations to respond to and absorb the needs of the displaced.

Figure 1.1 IDP and refugee figures by region

Note: Country figures for internal displacement have been reported during the first half of 2002. The Global IDP Database has not collected the country figures itself, but relies on information made available by different public sources. Where lack of humanitarian access has made it impossible to compile anything but rough estimates, the Global IDP Database has calculated a median figure using the highest and lowest available figures. Refugee statistics come from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR's) provisional 2001 statistics released in May 2002.

Source: Global IDP Database, April–May 2002; UNHCR, 16 May 2002

Figure 1.2 Ratio of displaced versus resident populations in selected countries (2002)

Source: Global IDP Database, April–May 2002; UN Population Fund, 2001

Still, the well-being of IDPs is impossible to quantify as statistics rarely reflect the gravity of humanitarian needs. Over the last year, some of the most vulnerable populations have been much smaller in size. In West Africa, for instance, continued fighting in the Mano River region countries of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea has been accompanied by widespread human rights abuses, putting both the internally displaced and resident populations at risk. In Liberia, a dangerous environment at the end of 2001, characterized by extra-judicial executions, torture and widespread rape, forced many civilians to hide and trek through dense forests for weeks. Human rights conditions for IDPs in the Russian Federation and, in particular, Chechnya also continue to be a subject of serious concern.

In still other countries, detailed information about the welfare of civilian populations is piecemeal at best. Only limited information is available about IDPs in Algeria, Iraq, Kenya and north-eastern India, where the human rights situations are reported to be grave.

Factors causing displacement

As documented throughout this book, the main factors leading to ‘conflict-induced’ displacement include armed conflict, generalized violence, the systematic violation of human rights and the forced displacement or ‘dislocation’ of people as a primary military or political objective of either government or rebel forces.

In each and every one of the 48 countries contained in this survey, the lack of respect for fundamental human rights and humanitarian law principles by security forces or insurgent groups – and usually both – has been a leading cause of the mass flight of civilians. Indiscriminate attacks, massacres, torture and other inhuman treatment are part and parcel of the vast majority of conflicts surveyed in this book. In many cases, civilian populations are not only exposed to the dangers of armed combat, but are even targeted as a result of their presumed affiliation with the opposing forces.

In Colombia – a country with one of the highest levels of political violence – assassinations, threats of physical harm and other forms of intimidation are the primary reasons cited by civilians for fleeing their homes. In fact, it is noted in this survey that direct confrontations between different armed groups are not common in Colombia, and that parties to the conflict more commonly seek to weaken their adversaries or gain access to territories by attacking civilians suspected of sympathizing with the ‘other side’.

The ‘you are either with us or against us’ attitude taken by some armed forces towards civilian populations has unfortunately gained ground since the launch of the global ‘war on terrorism’ in late 2001. Following the terrorist attacks on the US in September 2001 and the subsequent US-led bombing of Afghanistan, various governments appear to be exploiting the global alliance against terrorism in order to strengthen their stance against insurgent groups in their own countries. In many instances, this has led to a concentration of security forces in civilian areas suspected of harbouring so-called ‘terrorists’.

The example most covered by the international media in 2002 of reinvigorated state efforts to counter terrorism is the Israeli campaign in the Palestinian Territories. Following a marked rise in suicide bombings against Israeli civilians in 2002, Israeli forces have struck back, conducting military operations in direct proximity to civilian settlements during the course of the year. However, the Middle East is certainly not the only place where events appear to have been influenced by the new anti-terrorism landscape. Other governments that have intensified counter-insurgency efforts during 2002 include Colombia and The Philippines; perhaps not coincidentally, both receive significant US support.

Further to the civilians displaced as a result of direct exposure to armed hostilities, a large number of persons described in this book have been victim to forced displacement or dislocation policies and operations. In 26 of the 48 countries studied in this survey, political and military policies conducted with the single aim of displacing communities have resulted in the movement of populations. Different country-specific justifications are given for pursued policies of forced dislocation. However, the main reasons behind this kind of displacement can generally be grouped into one of four categories:

- the forced relocation of populations by state and paramilitary forces as a means of isolating and combating insurgency movements;

- the state-ordered grouping of civilians into ‘peace villages’ and other settlements with the official aim of ensuring their greater protection and access to basic services (while unofficially depriving rebel groups of local support and at the same time securing a labour base to combat them);

- the sometimes decades-long political strategy of altering the demographic composition of a region by evicting or otherwise expelling indigenous populations considered undesirable and replacing them with other populations; and

- the struggle for control of strategic or resource-rich territories.

The oft-cited examples of forced dislocation of civilians are Sudan and Angola, the two countries in the world that are also host to the largest number of IDPs. In Sudan, government troops have been responsible for the aerial bombing of civilian targets – in many cases, as a means of clearing areas for oil-production and the construction of oil pipelines. In Angola, both the government and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) rebels have been blamed for the forced and repeated displacement of civilian populations. The government has evacuated villages in order to isolate UNITA troops; UNITA has forcibly displaced populations in order to get human and material support. In Burma, as well, hundreds of thousands of people have been forcibly relocated by government troops for the officially declared purposes of combating insurgency movements. Thousands of displaced people have been subject to forced labour in the process.

In Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda, the ‘re-groupment’, or ‘villagization’, of populations has been undertaken with the official objective of protecting civilian populations from armed conflict. Operations such as these have been criticized by human rights organizations, who characterize them as involuntary movements of civilians with the undeclared aim of depriving rebel forces of local support and regaining control of territory. ‘Protected villages’ in the north of Uganda have been the sites of abduction and sexual violence against children.

In still other situations, so-called ‘undesirables’ have been evicted or expelled from their indigenous communities as a result of policies to alter the demographic composition of a particular region. This has been the case in Iraq where the government has launched an ‘Arabization’ policy in oil-rich Kirkuk, and in Sudan where the government has sought to ‘Islamicize’ the Nuba Mountains by forcing out indigenous Nuba populations.

Human rights and humanitarian concerns

Unfortunately, the targeting, persecution and marginalization of these civilian populations do not cease after their initial displacement. As noted in chapter after chapter of this book, IDPs are subject to all forms of harm during the period of displacement, whether in private accommodation, in organized camps or in makeshift shelters on the outskirts of metropolitan centres. The most reported human rights abuses against IDPs are extra-judicial executions, torture, rape, sexual assault, abductions and forced recruitment. Those responsible for these violations are largely government and rebel forces. However, in some instances, civilian members of the resident population are also to blame.

While the greatest volume of human rights violations is reported out of the continent of Africa, extremely poor human rights records in Burma and Colombia – to name just two countries – underline the fact that IDPs are at high risk across the globe. The worst violations generally occur at the height of the fighting when perpetrators are more easily able to act with impunity. However, this can also be the case in protracted low-level conflict situations where the lack of a functioning police force encourages lawlessness and criminality. Such violations have often occurred in places as unlikely as the Solomon Islands and Mexico.

Gross human rights violations and subsequent displacement are also a major element in post-conflict situations where civilian populations associated with the ‘enemy’ have been targeted by civilian and military abusers. In Kosovo, for example, members of the ethnic Serb and Roma communities fled en masse during the period of Kosovo Albanian return in 1999, fearful of retaliation and revenge violence. More recently, in Afghanistan, civilian members of the Pashtun community have become the target of attack due to their ethnic association with the fallen Taliban regime. In both cases, isolated incidents have led to the displacement of still others following the main crisis period.

Women and children are widely recognized as the most vulnerable of IDPs. In camp and non-camp situations, they are victim to rape, sexual assault, forced recruitment and other forms of forced labour. Some of the countries with the worst records of forced child recruitment include Sierra Leone, Angola, the DRC, Sudan, Uganda, Burundi, Afghanistan, Colombia, Burma and Iraq. In Burundi alone, as many...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Internally Displaced People

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Editorial team

- Main contributing authors

- Acknowledgements

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Foreword by Dr Francis M Deng

- List of maps

- List of figures, tables and boxes

- List of photos

- Part 1: Issues and Perspectives

- Part 2: Regional Profiles

- UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement

- References

- Index