This is a test

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Content area teachers are now being tasked with incorporating reading and writing instruction, but what works? In this essential book from Routledge and AMLE, author Lori G. Wilfong describes ten best practices for content area literacy and how to implement them in the middle-level classroom. She also points out practices that should be avoided, helping you figure out which ideas to ditch and which to embrace.

Topics covered include…

-

- Building background knowledge quickly

-

- Using specific strategies to scaffold focus while reading

-

- Using small group reading strategies to bring personal response and accountability to the content

-

- Understanding items that make reading in different disciplines unique

-

- Teaching content area vocabulary in meaningful ways

-

- Making writing an authentic process through daily and weekly assignments

-

- Planning and teaching effective informational and argumentative pieces

Each chapter includes Common Core connections and practical templates and tools. The templates are available as free eResources so you can easily print them for classroom use.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Content Area Literacy Strategies That Work by Lori G. Wilfong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Build Background Information Quickly

As a fourth-grade teacher to a majority of English Language Learners, my colleague Stephanie worked extra hard to teach both content and context to her students. Social Studies was proving especially difficult: “We focus on Ohio history which is engaging but my students have such little knowledge about the United States, let alone the state we reside in!” She looked dolefully at the textbook that she usually uses to tackle the topic. “I can’t just announce that we are going to start reading. I have to bring them up to speed on state, national, and world contexts so it makes sense.” She sighed and thumped the textbook onto a back table. “Any ideas on how to do that and teach my standards in 47 minutes?”

Why Is This Item on the List So Important?

Stephanie is describing a scenario that all teachers face: To help a student comprehend a text or topic, we must build background knowledge. But in order to build background knowledge, we must use precious class minutes to activate what students already know so that they are ready to learn more. And in some cases, like Stephanie’s, students are blank slates; for many (often complicated) reasons, our students have little or no knowledge to build on. Diving into a topic does a disservice to our students and our content. These authors stated it well: “Put simply, the more you know about a topic, the easier it is to read a text, understand it, and retain the information” (Neuman, Kaefer, & Pinkham, 2014, p. 145).

Nonfiction text, the genre that most content area teachers use in their classrooms, requires background knowledge built around vocabulary (addressed in Chapter 5) and concepts (Price, Bradley, & Smith, 2012). As students progress in their learning, each standard is predicated upon learning in previous grade levels. Take Stephanie’s example from the anecdote at the beginning of this chapter: If a student has been in Ohio for their schooling, in third grade they will learn about community laws and how they fit into the vision of the state. If students are new to the state, or country for that matter, she needs to think about all the information they might need in order to access the current grade level’s standards.

One of the most difficult aspects of background building is the time it takes to do it well. Teachers walk a precarious line here—if I give too much background to my students, they have no interest in reading or learning about the topic. And if I spend too little time, I risk moving on with instruction that my students are not ready for.

“Do this, not that” principle #1: DO Build background information quickly. DON’T spend so much time building background information that students have no reason to read the actual text.

To Get Started

Awakening comprehension. Building background knowledge lays the foundation for eventual comprehension of a text or topic. This was once explained to me by someone who specializes in brain-based research by giving the analogy of a computer hard drive: When you write a new document on your computer and go to save it, you have to decide how you are going to organize this file on your computer. Which folder should it go in? You eventually tuck it away into a folder that makes sense to you. And yet, if you were to go through the files on my computer and make sense of my organization, it might not make sense. Our brains work in a similar way. When we learn something new, our brains are rifling through the “folders” on our “hard drive,” trying to find a connection for this new information to something we already know. Once it finds this connection, a synapse is literally formed—your brain is growing! But if you don’t have a piece of knowledge in your brain for this new information to latch onto, the new information can be lost. By building background knowledge with our students, we are building and accessing their brain “folders” to help them retain new information.

I can show this through a sentence:

The note was sour because the seam split.

Just by forcing you to read this sentence, I have activated the folders in your brain. You are rifling through your own knowledge, trying to make sense of what seems to be a wacky sentence. When I show this to learners, I get the following responses to the question, “What can this sentence possibly mean?”

- “I think of milk because of the word ‘sour.’” Milk is a popular answer because sour milk is something most of us have experienced at some point.

- “Wine comes to my mind, like if one of the “notes” of the wine went bad.” My wine drinkers often respond with this (sometimes embarrassed that they thought of wine!).

- “Maybe someone was singing and their pants split!” These are my choir people.

Generally, with each response, I can tell what kind of background knowledge each group has and how they used it to make sense of the sentence. So, when I show the sentence again, I add in a key word:

The bagpipe note was sour because the seam split.

Right then, your brain just said aha! It rifled through your folders and brought up a visual of a bagpipe player walking in a parade. You possibly heard in your mind the playing of that bagpipe. And then you were able to imagine what that bagpipe might sound like if the seam split. Sour, indeed!

Direct and indirect experiences. Robert Marzano (2004) states there are two ways to build background knowledge with students: direct and indirect experiences. Direct experiences like museum visits, travel, previous work in laboratory settings, and field trips offer powerful venues for students to build background knowledge (feel free to include that sentence the next time you have write a proposal for a field trip for your classroom). Our students’ direct experiences vary widely; we have students who travel and participate in cultural events while other students’ lives are narrowed to the walls of where they live and go to school. These individual experiences influence how students are able to process and extract information from a text (Kintsch, 1988).

A teacher recently shared an example of this from his high school social studies classroom:

We were discussing Hitler marching his troops down the Champs de Elysee and through the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and one of my students jumped out of her seat as if her pants were on fire! “I’ve been there,” she screamed, digging in her backpack to get her phone out. She scrolled through her photos and ran up to the front of the room to show me a selfie of her in front of the Arc. This student, who had been pretty uninterested before, was all of sudden the center of attention and paying attention because of that connection.

When I asked the teacher if many of his students traveled like that, he shrugged his shoulders: “Sadly, no. And some of the other kids were pretty jealous that she had been there.”

It is through indirect experiences that we can give other students access to content and build background knowledge. While it may not seem as powerful as a selfie under the Arc de Triomphe, indirect experience is how most of us build our background knowledge. Pictures, videos, skimming, social media, and discussion are all authentic ways that scientists and historians learn about a topic before diving into a dense text.

The tried and the true. There are some basic ways to build background information that we have all used before, including videos, webquests, and the good ol’ KWL. There is nothing wrong with these strategies and if you are already using them with success, continue! I have also written about a few pre-reading strategies in a previous book, Nonfiction Strategies That Work (Wilfong, 2014) that accomplish the same background building goal: Tea Party and Book Box.

Instructional Practices to Update

Updated Strategy #1: Carousel Walk (Lent, 2012)

One of the best places to access background knowledge is your students, themselves. As illustrated in the anecdote above about the selfie, when our students make personal connections or share their experiences with others, we are building background knowledge in an enjoyable, motivating way. But because we can’t wait for random acts of connection, we sometimes have to create these opportunities, ourselves.

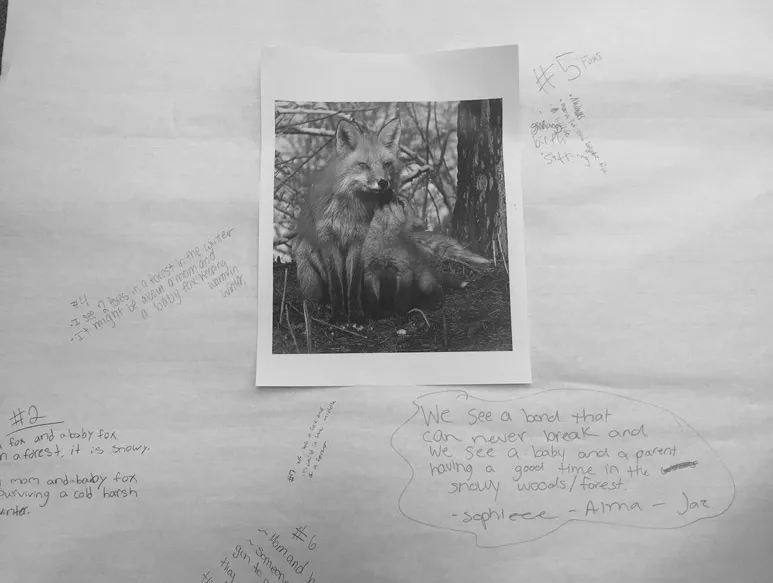

A carousel walk (Lent, 2012) allows student to do two things they love most, group work and graffiti. This strategy allows students to preview content in a motivating manner while building background knowledge through the collective understanding of their classmates. Here’s how to do it:

- Prior to the teaching of a unit or topic, identify five or six main concepts or terms that students will encounter. For example, for an eighth-grade science unit on energy, a teacher identified these six concepts: energy, mass, magnetic field, positive charge, and negative charge.

- Decide if you want to simply display these words or if you want to find images to show the word, or a combination of both. Depending on your learners, I find images a great way to spark a larger variety of conversations about the topic.

- Display your words or images on larger pieces of butcher paper. Be sure to leave a large border around the word or image to allow student written response.

- Hang the butcher paper pieces around the room, allowing space (if possible in a cramped classroom!) between them.

- Decision time!

- Can your students work in groups? Handle multiple voices talking at once? Then place your students in six groups and nominate person per group to be the leader by handing them a marker. Give each group a different colored marker. Assign each group to picture or word. Set a timer for three minutes. The group leader writes down anything a group member says about the word or picture (unless it is silly or illogical). When the timer goes off, groups rotate to the next picture and start the process again, but this time have the previous group’s work to use as a starting point. I do find that the number of minutes needed at each picture dwindles as the rotations continue—at some point, there are just not that many words one can write about a picture, word, or quote.

- Does your class function better as a unit? Then you take the marker and move your way around the classroom while your students stay seated. Write down your students’ suggestions for each topic.

- At the end of the exercise, you have accomplished two things:

- You have built a shared vocabulary around this topic.

- You have built background knowledge on this topic.

Figure 1.1 shows an example of a carousel walk from a science classroom.

Updated Strategy #2: Wide Reading (Fisher, Ross, & Grant, 2010)

Figure 1.1 Student Responses During a Carousel Walk

Wide reading is exactly what it sounds like—allowing a student to explore a topic through multiple texts (Fisher, Frey, & Hattie, 2016; Fisher, Ross, & Grant, 2010). To test a theory that wide reading could be applied to content area classrooms, researchers Fisher et al. asked students to peruse a set of materials in a high school physics class. Class then proceeded as usual—textbook reading, experiments, lecture, etc. Through just 10–12 minutes a day of reading, student knowledge of classroom learning, as measured on a textbook-created assessment, revealed statistically significant improvements (Fisher ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- eResources

- Meet the Author

- 1 Build Background Information Quickly

- 2 Help Scaffold Focus While Reading with Specific Strategies

- 3 Use Small Group Reading and Learning Strategies to Bring Personal Response and Accountability to the Content

- 4 Address Discipline-Specific Content Reading Strategies

- 5 Use Content Area Vocabulary in Meaningful Ways

- 6 Make Writing an Authentic Process in Every Classroom

- 7 Promote Daily Writing Strategies to Strengthen Thinking in the Discipline

- 8 Implement Slightly Larger Weekly Writing Strategies to Encourage Comprehension and Synthesis in the Discipline

- 9 Plan and Teach One “Big” Informational Piece Per Semester

- 10 Plan and Teach One “Big” Argumentative Piece Per Semester