CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

FIRST ENCOUNTERS

Think back to your childhood and your first encounter with a book, video, audiocassette tape, film, television show, or Internet source. How did you perceive the experience?Wally Lamb (1992) begins his book She’s Come Undone with Dolores’s first encounter with television:

In one of my earliest memories, my mother and I are on the front porch of our rented Carter Avenue house watching two delivery men carry our brand-new television set up the steps. I’m excited because I’ve heard about but never seen television. The men are wearing work clothes the same color as the box they’re hefting between them. Like the crabs at Fisherman’s Cove, they ascend the cement stairs sideways. Here’s the undependable part: my visual memory stubbornly insists that these men are President Eisenhower and Vice President Nixon.

Inside the house, the glass-fronted cube is uncrated and lifted high onto its pedestal. “Careful, now” my mother says, in spite of herself; she is not the type to tell other people their business, men particularly.We standwatching as the two delivery men do things to the set.Then President Eisenhower says to me, “Okay, girlie, twist this button here.” My mother nods permission and I approach. “Like this,”

he says, and I feel, simultaneously, his calloused hand on my hand and, between myfinger, the turning plastic knob, like one of the checkers inmy father’s checker set. (Sometimeswhenmyfather’s voice gets too loud atmymother, I go out to the parlor and put a checker in my mouth—suck it, passing my tongue over the grooved edge.) Now, I hear and feel the machine snap on. There’s a hissing sound, voices inside the box. “Dolores, look!” my mother says. A star appears at the center of the green glass face. It grows outward and becomes twowomen at a kitchen table, the owner of the voices. I begin to cry. Who shrank these women? Are they alive?Real? It’s 1956; I’m four years old.This isn’twhat I’ve expected.The twomen and my mother smile at my fright, delight in it. Or else, they’re sympathetic and consoling. My memory of that day is like television itself, sharp and clear but unreliable. (p. 4)

Lamb’s description touches on several topics we will be exploring. How do child and teen perceptions of television or any mass medium differ from the perceptions of adults? Not only do youth perceptions differ from those of adults as did those of Dolores from her mother, but they are different at various developmental ages. The context for the relationship of children, teens, and the media is presented in the first three chapters. The theoretical context is in this chapter (chapter 1). The development of children’s perceptions of mass media is the topic of chapter 2, and the changes in media experiences by generations is the topic of chapter 3.

What is real and what is fantasy? For 4-year-old Dolores, it was difficult to differentiate the deliverymen from the images of President Eisenhower and Vice President Nixon she later saw on the screen of the television. Stereotypical perceptions are normal at age 4. In addition, children up to age 8 cannot differentiate fantasy from reality. For Dolores, stereotypes and difficulty distinguishing fantasy from reality caused her to be fearful. Moving the television into the house was Dolores’s earliest memory. The physical placement of media utilities in the home and their function in the home can have an effect just as a perception can make the child afraid. The next three chapters examine how children, teens, and families react to mass media with perceptions of fantasy and reality (chapter 4), effects (chapter 5), and identity (chapter 6).

How can children better use the mass media as tools for their own empowerment? Dolores described the media’s “sharp and clear” pictures in contrast to their “reliability.” Chapters 7, 8, and 9 examine the mediation of families (chapter 7), schools through media literacy (chapter 8), and government and other policymakers (chapter 9). In the concluding chapter (chapter 10), we look at children’s programming and the industry that creates it.

DEFINITIONS AND CENTRAL IDEAS

Children and teen years are defined here as ages 2 to 18. Treating children as a separate developmental group is a fairly recent concept.

While children are mentioned in the Bible and in the writings of Plato, the idea that they ought to be protected, catered to and nurtured is a fairly recent notion in public discourse. That they are a constituency of the media in all of its functions—news and information, opinion, entertainment and marketing—is itself rather revolutionary. (Dennis & Pease, 1996, p. xix)

Although modern culture views children as a separate group to be nurtured, children and teens are not passive in the process. Rather, they are active in using mass media as part of their own socialization. When the dominant mass medium was print, children had to learn how to read before gaining access to information and entertainment. That barrier does not exist in the mass media of film, radio, television, video, and Internet. This accessibility of electronic media has brought the problems of the larger world into our homes and challenged the role of parents in raising children. Althoughwe have viewed children as a separate group in personal nurturing, society also has made exceptions for children in law and regulations. However, for mass media, only guidelines and voluntary arrangements persisted until the Children’s Television Act of 1990 (see chapter 9, “Policy and Law”).

Mass media are those channels of communication that reach the wider audience simultaneously with their messages. Although print media are mass media, the focus here will be on the electronic home utilities of radio, television (and variations including broadcast, cable, satellite, video, and DVD), and the Internet. Film is an outside-the-home medium except as it is found on video. Being available only outside the home, film requires cost and sometimes transportation and adult supervision,which media inside thehomedo not. Mass media have become a home utility and with this home utility status, they seem to be challenging families as a primary socializing agent by bringing the larger world into our homes.

Children, teens, and families have a complicated relationship to mass media that varies with age, gender, generation, and family environment. Children’s understanding of media changes as they grow. Each generation experiences and perceives media differently as well.

Millennial children and teens are those who have the high school graduation date of 2000 and beyond. Strauss and Howe (1991) set the dates for the millennial generation as those born in 1982 and later. Millennial children come of age by year 2000 or later and live as adults in the newmillennium. Dramatic events the mass media bring to each generation when that generation is coming of age may mark the beginning of that generation’s adult consciousness. The events of September 11, 2001, although affecting the consciousness of all Americans, may mark the beginning of and perhaps the nature of the millennial generation’sworldviewand relationship to the mass media (see chapter 3, “Generations and History”). The media world as it has developed for this millennial generation is a focus of this book.

COMMUNICATION MODELS

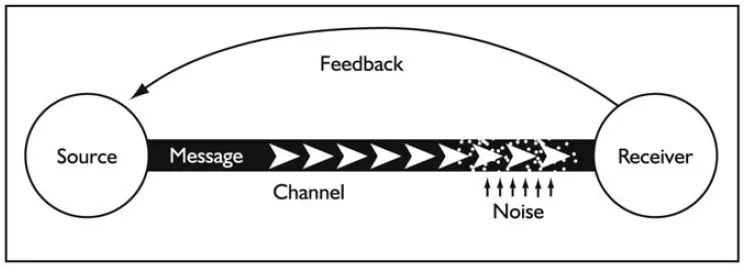

The complicated relationship between children and media can be mapped using a communication model. With our focus on a particular audience, the millennial generation, and particular channels of radio, television, and Internet, we now look at the other elements of the communication model. A communication model can represent children’s use of media. However, that model has some extra variables we need to consider. The basic communication model includes a source that encodes a message that goes through a channel to a receiver who decodes the message. During the process, noisemay interfere with or interrupt the message. After receiving the message, the receiver may provide some feedback for the source (see Fig. 1.1).

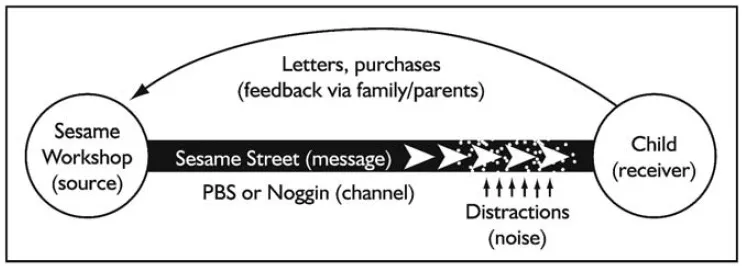

For our example, we try to apply the communication model to a 4-year-old watching Sesame Street on television (see Fig. 1.2). The source has several layers including public television, the Children’s Television Workshop (now called SesameWorkshop), and the producers and characters for the individual show. The encoding process also is multilayered and includes writing the script, taping the show, and preparing the show for satellite transmission. The channel is the satellite, cable system, and television reception the show may go through to reach the child. The channel might also include the videotaping at the home for multiple viewings, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) or Noggin (cable channel). The message for programs such as Sesame Street is often a prosocial message, such as how to get along and interact with other children. The child, of course, is the receiver, but others may include siblings, parents, or adult caregivers. The child’s communication process in this case seems to require an additional variable not included in the general communication model, the mediator between the child and the message, someone who explains or discusses the message with the youth. Thus, the child decodes the message in an environment that may include adult mediation and explanation of the messages. Noise that may interrupt or interfere with a child’s understanding of the message includes the physical noise that may occur in the channel or the environment, but can also include the distraction of toys or other youth or adults. In addition, the noise may arise from the child’s inability to understand the level at which the message is addressed. Thus the need for an older youth or adult to answer questions has been built into the Sesame Street message by having a multiple- level approach in which guests come on, unnamed, who are recognizable to the older youth or adult but not to the 4-year-old child. The celebrity guests make involvement in the communication by older family member more rewarding. Feedback also differs from the standard model in that the older youth or adult may mediate the feedback the child may have to the program. The feedback may be in the form of buying a product such as Tickle Me Elmo or letters from the parent to the public television station about their child’s reaction to the show.

FIG. 1.1. Communication model.

FIG. 1.2. Child and TV model.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

In addition to mapping the relationship with models, we can try to explain and predict the relationship with theories. A theory tries to explain and pre-dictwhat will happen in certain circumstances under a given set of assumptions. Theories come from a variety of disciplines including ethics, communication, and psychology. Different theories may also focus on different parts of the communication model, such as the message, the medium, or the receiver. We want to know what causes behavior such as violence, fear, and sexuality. When children in schools behave violently as in the school killings of the late 1990s or imitate the World Trade Center terrorists as one Florida boy did, we want to know what caused that behavior and what we as a society can do to prevent it.We can examine some theories that may help us predict what will happen in the communication process between children and the media.

The theories examine various aspects of the communication model. Some of the theories we examine are macro theories, or theories that examine the larger society. Other theorieswe examine are micro theories, or theo- ries that examine the individual. Over time, electronic technology has gone from unidirectional broadcast radio and television to the more interactive Internet. The changes in media channel technology parallel the changes in theory that grew to focus more on the receiver and individual use of the media as the 20th century came to a close. As media have become interactive, so have research findings. Some theories focused on the source of the messages and their intent.

Moral Man and Immoral Society by Reinhold Niebuhr

A theoretical overview of the relationship of any individual to society is one place to begin our search for theoretical tools. Firstwe can look at a theoretical perspective that focuses on the source of the message in our communication model. To characterize the media–child–parent relationship, Steyer (2002) referred to media as “The other parent.” Thus the source, a societal force, takes the role of parent, an individual source. However, one theory calls society immoral and says the immorality on the societal level conflicts with the moral individual.

The author of Moral Man and Immoral Society, Reinhold Niebuhr (1960) took the view that although the individual is a moral and ethical creature, society at large lacks that same dedication to issues of morality: “As individuals, men believe that they ought to love and serve each other and establish justice between each other. As racial, economic and national groups they take for themselves, whatever their power can command” (p. 9).

For the youth’s relationship to mass media, this theoretical perspective helps to explain the discrepancy between the socialization the child receives from parents and the differing ethical messages mass media may provide. For example, the familymay try to teach youth to resolve problems peacefully. However, media advertisers and producers (sources in the larger society) are interested in the profit they can earn by using violence to attract viewers.The goals of family and society thus differ.

Walsh (1994) used N...