![]()

1 Agricultural systems

1.1 Introduction

Agriculture, or farming, is the rearing of animals and the production of crop plants through cultivating the soil (Mannion, 1995a, p. 2). It is a manifestation of the interaction between people and the environment, though the nature of this interaction has evolved over a period of at least 10,000 years since the first domestications of wild plants began in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East around 10,000 years before present (BP) (MacNeish, 1992). Sheep, pigs, goats, cattle, barley and wheat were first domesticated in this area, followed by six other independent origins of agriculture: East Asia (between 8400 and 7800 BP) utilising rice, millet, pigs, chickens and buffalo; Central America (4700 BP) and South America (4600 BP) produced potato, maize, beans, squash, llama, alpaca and guinea pigs; North America (4500 BP) had goosefoot and sunflower, whilst Africa (4000 BP) had cattle, pigs, rice, millet and sorghum.

The domestication of plants and animals spread from the Near East into south-eastern Europe, where the combination of improved cultivation methods and an extensive trading network supported first the Greek and then the Roman empires. It was these that gave rise to the term ‘agriculture’, which is derived from the Latin word agar, and the Greek word agros, both meaning ‘field’, and symbolising the integral link between land-based production and accompanying modification of the natural environment (Mannion, 1995b).

This modification produces the agri-ecosystem in which an ecological system is overlain by socio-economic elements and processes. This forms ‘an ecological and socio-economic system, comprising domesticated plants and/or animals and the people who husband them, intended for the purpose of producing food, fibre or other agricultural products’ (Conway, 1997, p. 166). Agricultural geographers have viewed this agri-ecosystem as part of a nested hierarchy that extends from an individual plant or animal and its cultivator, tender or manager, through crop or animal populations, fields and ranges, farms, villages, watersheds, regions, countries and the world as a whole.

Agricultural geography includes work that spans a wide range of issues pertaining to the nature of this hierarchy, including the spatial distribution of crops and livestock, the systems of management employed, the nature of linkages to the broader economic, social, cultural, political and ecological systems, and the broad spectrum of food production, processing, marketing and consumption. The principal focus for research by agricultural geographers in the last four decades has been the economic, social and political characteristics of agriculture and its linkages to both the suppliers of inputs to the agri-ecosystem and to the processing, sale and consumption of food products (Munton, 1992). However, it should not be forgotten that at the heart of farming activity, underlying the chain of food supply from farmers to consumers, is a set of activities directly dependent upon the physical conditions within which farming takes place. Hence, before concentrating upon the principal foci of contemporary agricultural geography in the rest of the book, this chapter outlines the key physical aspects of agriculture that form the foundations to which the multi-faceted human dimensions of farming activity are applied.

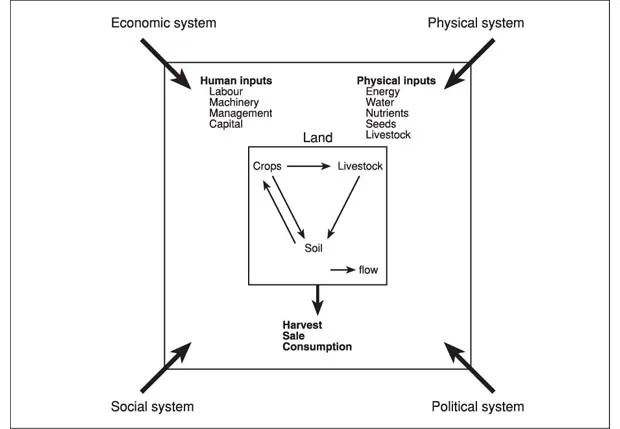

Six key factors can be recognised as influencing the distribution of farming types: biological, physical, economic, political, socio-cultural and marketing (the food trade) (Ganderton, 2000, p. 161). These factors are part of the simple conceptualisation of a farming system shown in Figure 1.1, in which a series of inputs to the land generates a series of outputs. Social, economic, political and environmental factors affect the nature of these inputs and outputs, producing tremendous variation in the pattern of the world’s farming systems. This chapter examines the nature of the physical basis to agriculture and considers the role that physical and other factors play in determining the nature of farming systems.

Figure 1.1 Simple conceptualisation of a farming system

1.2 The agri-ecosystem

Unlike many aspects of economic activity, the contributions made by the physical environment can be of fundamental significance to the nature of the farming system. In the Developed World especially, farmers may have capital at their disposal to enable purchase of inputs that can substantially modify some of the physical characteristics of the land upon which farming is based. Yet, the changeable nature of weather and hydrological regimes can inject elements of risk and uncertainty unknown to other areas of economic activity. Despite the influence of non-physical factors upon farming, farming retains strong parallels with the natural ecosystems from which agricultural systems derive, and hence farming can be portrayed as an agri-ecosystem.

There is a reciprocal relationship between environmental factors and agricultural activity. Environment affects the nature of farming, exerting a wide range of controls, but, in turn, farming affects the environment. Agricultural systems are modifications of natural ecosystems; they are artificial human creations in which productivity is increased through control of soil fertility, vegetation, fauna and microclimate. This is intended to generate a greater biomass than that of natural systems in similar environments, though this may also generate undesirable environmental consequences. In particular, farming alters the character of the soil and, through runoff, effects can be extended to neighbouring areas, e.g. nitrate pollution of the watercourses and groundwater, and effects on wildlife (Parry, 1992).

Agriculture can also be differentiated from many other economic activities by virtue of the fact that it deals with living things. The plants and animals have inherent biological characteristics that largely determine their productivity. They function best in environments to which they are well adapted, and this exerts a strong influence on the nature and location of agricultural production. Despite the diversity of agricultural systems they all have many common features, notably the human control of ecosystems, for example by varying the amounts of energy inputs. The extent and exact nature of this control varies largely in response to social and economic requirements. However, the control is also affected by environmental characteristics acting as constraints.

In an agri-ecosystem the farmer is the essential human component that influences or determines the composition, functioning and stability of the system. The system differs from natural ecosystems in that the agri-ecosystems are simpler, with less diversity of plant and animal species and with a less complex structure. In particular, the long history of plant domestication has produced agricultural crops with less genetic diversity than their wild ancestors. In agri-ecosystems the biomass of the large herbivores, such as cattle and sheep, is much greater than that of the ecologically equivalent animals normally supported by unmanaged terrestrial ecosystems. Cultivation means that a higher proportion of available light energy reaches crops and, because of crop harvesting or consumption of crops by domestic livestock, less energy is supplied to the soil from dead and decaying organic matter and humus than is usually the case in unmanaged ecosystems in similar environments. Agri-ecosystems are more open systems than their natural counterparts, with a greater number and larger volume of inputs and outputs. Additional inputs are provided in the form of direct energy from human and animal labour and fuel, and also in indirect forms from seeds, fertilisers, herbicides, pesticides, machinery and water. The dominant physical or natural resource inputs to the farming system are climate and soils.

1.3 Climate and agriculture

The greatest physical constraints upon agricultural activity are generally imposed by average te...