![]()

| 1 | Issues in the Acquisition of Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian: A Crosslinguistic Comparison |

Lisa Dasinger

University of California, Berkeley

1. Introduction

2. Descriptive Sketch of Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian

2.1. Phonology

2.1.1. Phonemes

2.1.2. Word Stress

2.1.3. Phonological Alternations

2.1.3.1. Quantity

2.1.3.2. Vowel Harmony

2.2. Morphology

2.2.1. Nominal System

2.2.1.1. Nominal Cases

2.2.2. Verbal System

2.3. Morphophonemics

2.3.1. Gradation

2.3.2. Other Morphophonological Rules and Classes

2.4. Word Order

2.5. Summary: Convergences and Divergences

3. Sources of Evidence

4. Data

4.1. Early Acquisition

4.1.1. Quantity

4.1.2. Vowel Harmony

4.2. Error-Free Acquisition

4.2.1. Word Segmentation

4.2.2. Ordering of Bound Morphemes

4.3. Prolonged Acquisition

4.3.1. Locative Development

4.3.1.1. Theoretical and Grammatical Background

4.3.1.2. Deictic Adverbs

4.3.1.3. Locative Cases

4.3.1.4. Locative Postpositions

4.3.1.5. Language-Specific Influences

4.3.2. Morphophonology

4.3.2.1. Finnish

4.3.2.2. Hungarian: A Comparison with Finnish

5. Conclusion

1. Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian Acquisition

1. INTRODUCTION

Estonian (eesti keel), Finnish (suomi), and Hungarian (magyar) are members of the Finno-Ugric family of languages. Estonian and Finnish belong to the Finnic branch, more specifically, Balto-Finnic, which also includes Ingrian, Karelian, Livonian, Ludian, Olonetsian, Vepsian, and Votian. The Permic and Volgaic branches consist of Zyryan (Komi) and Votyak (Udmurt) and Cheremis (Mari) and Mordvinian, respectively. Lappish (Saami) is taken to represent a separate branch of Finnic (see, e.g., Itkonen, 1955; Ravila, 1935). In the Ugric branch are Hungarian and the Ob-Ugric languages, Vogul (Mansi) and Ostyak (Khant), whose present status as sub-branches, rather than separate main branches of Finno-Ugric, has been disputed (Comrie, 1981). The Finno-Ugric languages form one part of the superordinate structure Uralic, with Samoyedic constituting the smaller branch.

Table 1 provides figures for the numbers of speakers and main areas of distribution of each language, as furnished by the Department of Finno-Ugrian Studies at the University of Helsinki (1993).1 Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian are not only the most highly represented languages, based on the number of people who speak them, but are also the only languages which constitute the primary tongue for the people in the countries in which they are spoken.2 The people also claim the status of being the most highly incorporated into the European cultural and economic community. For the purposes of the present chapter, they are the only languages of the Finno-Ugric group, to the best of my knowledge, for which published acquisition studies are available.3 Unfortunately, a handful of Finno-Ugric languages—namely Livonian, Votian, and Ingrian—are spoken by so few nowadays that they may never bear the fruits of acquisition research.

TABLE 1

Number and Areal Distribution of Speakers of Finno-Ugric Languages

Language | Number of Speakers | Area of Distribution |

Finnic | | |

Balto-Finnic | | |

Livonian | very fewa | Latvia |

Estonian | 1,000,000 | Estonia and adjacent areas |

Votian | very few | Russia |

Finnish | 5,000,000 | Finland and adjacent areas |

Ingrian | 300 | Russia |

Karelian and Olonetsian | 70,000 | Russia, Finland |

Ludian | 5,000 | Russia |

Vepsian | 6,000 | Russia |

Lappish | 34,900 | Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia |

Permic | | |

Votyak | 500,000 | Russia |

Zyryan | 350,000 | Russia |

Volgaic | | |

Cheremis | 550,000 | Russia |

Mordvinian | 750,000 | Russia |

Ugric | | |

Hungarian | 14,000,000 | Hungary and adjacent areas |

Ob-Ugric | | |

Vogul | 3,000 | Russia (extinct), Siberia |

Ostyak | 13,000 | Siberia |

The genetic affinity of Hungarian with the Finnic languages was definitively established as early as 1799, with the publication Affinitas linguae Hungaricae cum linguis fennicae originis (Grammatical proof of the affinity of the Hungarian language with languages of fennic origin) by Sámuel Gyarmathi. Despite the genetic relationship, Estonian and Finnish on the one hand, and Hungarian on the other, are in many respects radically different from each other in phonology, syntax, morphology, and lexicon. This is not surprising, considering the fact that the split between Proto-Finnic and Proto-Ugric is postulated to have occurred sometime around the end of the third millennium B.C., or even earlier (see, e.g., Hajdú, 1972). In fact, we can say of the language group as a whole that it does not lend itself to typological pigeonholing; the languages which constitute it represent a rather heterogeneous set. A prime example of this lack of homogeneity is in the area of basic word order, some languages preferring verb-final order (e.g., the Ob-Ugric languages), others verb-medial (e.g., the Balto-Finnic languages), and yet a third group having two basic word orders (e.g., Hungarian).

Nevertheless, the lack of homogeneity does not preclude the making of interesting crosslinguistic comparisons between the languages of this group. As we shall see, the relatively close relationship between Estonian and Finnish allows for comparisons in which small degrees of variation in the expression of grammatical categories present the researcher with a valuable research tool in unraveling similarities and differences in acquisition. Further, Hungarian’s extensive case system evidences striking similarities to those of Estonian and Finnish in both the kinds of grammatical distinctions which are encoded and the general morphological means for expressing them, despite the fact that much of this system developed entirely independently, after the Finno-Ugric split (see, e.g., Abondolo, 1987; Comrie, 1988). Needless to say, each language presents relatively unique characteristic features which serve to expand our understanding of child language learning and development. These issues are taken up in the data section, which presents a group of strategically selected areas of acquisition as small comparative case studies. The language family as a whole will be returned to in the concluding section, where suggestions for further research are offered.

2. DESCRIPTIVE SKETCH OF ESTONIAN, FINNISH, AND HUNGARIAN

Descriptive sketches of Finnish and Hungarian are provided by the authors of the corresponding chapters in these volumes (see Toivainen, this volume, for Finnish, and MacWhinney, 1985, volume 2, for Hungarian). In order to illuminate the place of Estonian in relation to these languages, and the similarities and differences which constitute some of the core issues for their comparative acquisition, some grammatical features of Finnish and Hungarian already described in the aforementioned chapters are necessarily repeated, sometimes with magnification of the level of detail where close comparisons warrant this. The focus of this section is therefore on features which are directly relevant to issues of crosslinguistic research, some of which will be specifically addressed later in the light of available data. Although the focus of this section is on the main areas of contrast, I have endeavored to give a sense of the overall flavor of these languages, with a slant toward Estonian and Finnish, in order to illustrate some of the fine-grained comparisons possible with these two languages.

General overviews of the Finno-Ugric family and chapters on specific languages within the group can be found in Comrie (1981, 1987), Sinor (1988), and Tauli (1966). Comrie (1987), in his edited volume, presents an overview of the Finno-Ugric languages in his chapter “Uralic languages” (see also Comrie’s contribution in Sinor, 1988), which includes individual chapters on Finnish (Branch, 1987) and Hungarian (Abondolo, 1987). The most complete monograph-length grammar of Finnish for the English reader is Karlsson (1983), which can be supplemented by Hakulinen (1961), who addresses both diachronic and synchronic aspects, and Sulkala and Karjalainen (1992), for a more typologically oriented perspective.

The availability of comprehensive Hungarian grammars in English is limited. MacWhinney’s (1985) textbook suggestion of Bánhidi, Jókay, and Szabó (1965) can be substituted by Lotz’s (1939) reference grammar for readers of German. Benkő and Imre (1972) provide an edited collection which contains a grammatical overview chapter by Károly (1972). More recently, the first volume of the four-volume series entitled Approaches to Hungarian, edited by Kenesei (1985), is a nontheoretical introduction to the major features of the language, the later volumes taking up topics within specific theoretical approaches (Kenesei, 1987, 1990; Kenesei & Pléh, 1993).

With regard to Estonian, Raun and Saareste’s (1965) Introduction to Estonian linguistics is a general work with sections on grammar, aspects of the history of the language, its study, and dialectology. Tauli (1973, 1983) contributes a rather idiosyncratic two-volume work on Estonian; Part I covers the topics of phonology, morphology, and word formation, and Part II is devoted to syntax. I have also found the two Estonian textbooks, Oinas (1966) and Oser and Salasoo (1992), and Aavik’s grammatical survey contained in the Estonian-English dictionary compiled by Saagpakk (1982) useful resources. Matthews (1954) is an article-length account of the major features of the Estonian language.

2.1. Phonology

2.1.1. Phonemes

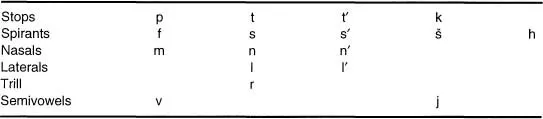

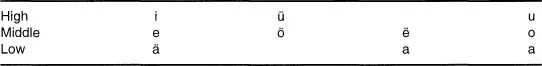

The phoneme inventory for Hungarian is presented in MacWhinney (1985). Estonian and Finnish share some features with Hungarian, particularly in the vowel system (e.g., the presence of the front rounded vowels ö and ü), but present a rather different profile with respect to their consonantal inventories, which are much less extensive than that in Hungarian (e.g., Hungarian has four affricates and a system of voiced/voiceless oppositions). Estonian and Finnish also contain a large number of diphthongs (16 in Finnish and around 20 in Estonian), a feature which does not occur in standard Hungarian apart from its presence in some words of foreign origin, but which is found in many dialects. Tables 2 and 3 lay out the phoneme inventory of Estonian (from Raun & Saareste, 1965), which is so close to Finnish that we need only remark cursorily on the divergences (see below).4 With respect to Estonian orthography, the palatalized series /t′ s′ n′ l′/does not receive distinct representation, and the vowel /ë/ is signified by õ. The phonemes /f/ and /š/ entered the language through recent loanword borrowings, but have become fully integrated into the Estonian sound system, as evidenced by their participation in quantitative alternation (see section 2.3.1).

TABLE 2

Estonian Consonants

Source: Raun and Saareste (1965).

The differences between Estonian and Finnish lie in Finnish’s lack of the palatalized series and the mid-central or back unrounded vowel /ë/ and the presence of the morphologically conditioned voiced stop /d/. Orthographic convention substitutes the Estonian letter ü for y. Thus, the word for the numeral ‘one’ is written üks in Estonian but yksi in Finnish. Estonian orthography, like that of Finnish and Hungarian, is close to phonemic, excluding only the indication of stress, palatalization, and some distinctions between the long and overlong duration.

2.1.2. Word Stress

In all three languages, main word stress falls on the first syllable, except in some loanwords in Estonian and certain emotive expressions, for example, Finnish oho ‘oops’ and Estonian aitäh /aitähh/ ‘thanks’, where primary stress falls on the second syllable. This prosodic feature may facilitate word segmentation (see Peters, 1981, 1983, 1985, 1997, for a treatment of this topic with respect to the acquisition of different languages).

2.1.3. Phonological Alternations

TABLE 3

Estonian Vowels

Source: Raun and Saareste (1965).

Of particular interest to the child language researcher are two phonological alternations which are among the main characteristic features of the three languages under study, namely quantity, or duration, and vowel harmony. A third alternation, gradation, will be discussed in section 2.3.1 in the section on morphophonolog...