This is a test

- 612 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Politics, Economics, and Welfare

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

For most of this century, the habit of thinking about politics and economics in terms of grand and simple alternatives has exerted a powerful influence over the minds of those concerned with economic organization. Politics, Economics, and Welfare is a systematic attack on the idea of all-embracing ideological solutions to complex economic problems.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Politics, Economics, and Welfare by Robert A. Dahl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I.

INDIVIDUAL GOALS AND SOCIAL ACTION

1. | Social Techniques and Rational Social Action |

I. Introduction

GRAND ALTERNATIVES AND THE “ISMS”

In economic organization and reform, the “great issues” are no longer the great issues, if ever they were. It has become increasingly difficult for thoughtful men to find meaningful alternatives posed in the traditional choices between socialism and capitalism, planning and the free market, regulation and laissez faire, for they find their actual choices neither so simple nor so grand. Not so simple, because economic organization poses knotty problems that can only be solved by painstaking attention to technical details—how else, for example, can inflation be controlled? Nor so grand, because, at least in the Western world, most people neither can nor wish to experiment with the whole pattern of socioeconomic organization to attain goals more easily won. If, for example, taxation will serve the purpose, why “abolish the wages system” to ameliorate income inequality?

Still, the older point of view is not entirely abandoned; it crops up in unexpected places. “The irrational and planless character of society,” Erich Fromm writes, “must be replaced by a planned economy….”1 He does not say, however, what is to be planned, or how, or for what particular purposes; only that “self-realization for the masses of people requires planning.”

Even Schumpeter2 sometimes writes in terms of mythical grand alternatives, introducing, it has appeared to some of his readers, “an anthropomorphic supernatural force, capitalism, which becomes the operating force in history.”3 His concept of socialism is in one context sophisticated, in another naïve, because socialism to him is sometimes a product of an accumulation of incremental changes and at other times a system consciously chosen in a particular time and place as an alternative to capitalism. Writing of socialism as planning, he says: “A situation may well emerge in which most people will consider complete planning as the smallest of all possible evils.”4 The starkness of the alternative, the notion of “complete planning” (what can it mean?) are earmarks of a disappearing point of view.

For all their contributions to our understanding of economic organization, Schumpeter, Hayek,5 Lippmann,6 Mises,7 and a host of socialists or planners like Jay,8 Beckwith,9 Lorwin,10 Landauer,11 Lange,12 and Mannheim13 (to say nothing of the older doctrinaire socialists and communists) are to various degrees enmeshed in the now vanishing tradition of the great “isms.” The grand alternatives they envision are the ignes fatui of Right and Left alike. Capitalism is now hardly more than a name stretched to cover a large family of economies in which distant cousins, it is true, resemble one another, but no more than do “capitalist” United States and “socialist” Britain. Socialism once stood for equality; but income and inheritance taxation, social security and other techniques of “capitalist” reform have destroyed its distinction. And in the eyes of socialists themselves, public ownership of industry is now simply an implement in everyone’s tool kit for economic reform. Socialism has lost its unique character.

Plan or no plan? Everyone believes in planning in the literal sense of the word; and, for that matter, everyone believes that national governments should execute some plans for economic life. No one favors bad planning. Plan or no plan is no choice at all; the pertinent questions turn on particular techniques: Who shall plan, for what purposes, in what conditions, and by what devices? Free market or regulation? Again, this issue is badly posed. Both institutions are indispensable.

In 1894 Beatrice Webb speculated on how later generations would regard the debate on collectivism. “They will be amazed,” she wrote, “that we fought so hard to establish one metaphysical position and to destroy another.”14 Believing that reform posed problems of techniques, not grand alternatives, some of the other Fabians shared Beatrice Webb’s view of the then current debate.15 Although the present generation has not advanced so far beyond Mrs. Webb’s that it can yet be amazed at her contemporaries’ error, it is at least slowly escaping from the tyranny of the “isms.”16

Of course great issues remain. Because the whole is sometimes greater than the sum of its parts, another step in a series of reforms may produce more for good or bad than the modest results expected. Reform may pass through breaking points. Even so, further debate on the old alternatives shows no promise of discovering these points, if there are any. Nor does it succeed in turning attention to the countless particular social techniques out of which “systems” are compounded.

SOCIAL TECHNIQUES

In economic life the possibilities for rational social action, for planning, for reform—in short, for solving problems—depend not upon our choice among mythical grand alternatives but largely upon choice among particular social techniques.

THE VARIETY OF POLITICO-ECONOMIC TECHNIQUES. The number of alternative politico-economic techniques is tremendously large. For example, the alternative forms of business enterprise are numerous. One is called private enterprise, but its alternative forms in turn are many. Proprietorship, partnership, and corporation are terms suggesting three kinds of alternative structures significantly different one from the others. Corporations may be relatively simple structures for family ownership or complex bureaucracies with or without owner control. And a corporation operating under a minimum of regulation is different from one subject to securities and exchange regulation; different again from one embedded in a matrix of regulations developed through collective bargaining, from one operating under the ever present threat of antitrust action, or from one subject to rate regulation. The Filbert Corporation, the Ford Motor Company, American Telephone and Telegraph, General Motors, Hart-Schaffner-Marx, Kennecott Copper, and the Pennsylvania Railroad are all corporations; but as techniques for the organization of production they differ from one another in ways quite significant for policy. Whatever the problem, whatever the goal, the number of significantly different alternative techniques will ordinarily be great.

INNOVATION IN POLITICO-ECONOMIC TECHNIQUES. Moreover, the number of alternative techniques is constantly growing by discovery, invention, and innovation. To return to the example of alternative forms of private enterprise, in the United States the Atomic Energy Commission has developed a rather distinctively new form of enterprise, although one similar to the organization of business through contracts in war. Through their contractual relations with the commission, Union Carbon and Carbide, Tennessee Eastman, General Electric, and other companies are operating under a different structure of cues and incentives from those of the other corporate forms mentioned above. Profit, in the ordinary sense of the term, is gone. So also is independence of investment decisions; price and production polices are subject to negotiation. Yet much of the initiative remains in the hands of the corporations, and their autonomy in a wide variety of decisions is relatively unaffected.

Many people think of invention and innovation in technology, but not in social structure; the bias probably accounts for a frequent failure to take account of the increasing possibilities for rational social reform through the improvement of techniques. We need only list a few inventions and discoveries to observe how they have increased the possibilities of rational social action, even if they often bring new problems in their wakes. The corporation itself was once an innovation; so also were unemployment compensation, food stamps, cost accounting, zoning, Lend-Lease, coöperatives, scientific management, points rationing, slum clearance, government old-age pensions, disability benefits, collective bargaining. Their origins are not so far distant that we cannot visualize a kind of accumulation of competence. Today, the European Payments Union and the Schuman Plan attest the inventiveness of our times.

RATE OF INNOVATION. The rate of increase in techniques is now extremely rapid. Why this is so must be a matter of speculation until the process of invention of social techniques is systematically studied. One hypothesis is that the growth of democracy has made it possible for masses of people to insist that problems be attacked where earlier the absence of any obvious solution to a problem was sufficient to deter any sustained efforts to solve it. Then, too, not until power is made democratic are the frustrations of masses of people necessarily the problems of public policy. Either way, the incentive to think constructively in terms of techniques is now much heightened. Another hypothesis, a corollary of what we have said, is that reform is turning to techniques instead of grand alternatives. A third hypothesis is that in the last few years war and defense have immensely stimulated the search for social as well as technological devices for social control, as is illustrated by the work of the RAND Corporation.

A fourth hypothesis is that the discovery and invention of new social techniques are largely the product of the social sciences, which are themselves relatively new. The particular role of psychology has recently been conspicuous in providing social scientists with a wealth of ideas on how men may be influenced. Lastly, literacy, popular education, and technological revolutions in communication have provided a groundwork for many new patterns of cues and incentives. There are no doubt still other explanations to be found in great shifts in culture such as the decline of traditionalism in Western society.

The process of innovation is both scientific and political. It is not enough that new social techniques be discovered; they must also be put into use. Invention and discovery are only the beginning of a process the next step in which is innovation, a matter of politics. What we are suggesting is that this process taken as a whole is proceeding with astonishing rapidity—it is perhaps the greatest political revolution of our times. Anyone who is not impressed with it can hardly gauge the richness—and dangers—of possible social reform and, failing that, he cannot deal competently with public policy.

Rational and responsible reform may consequently suffer from a serious limitation at the hands of those who fail to grasp the fact that alternatives are many, that new ones can be expected to appear, and that they can be created. A great deal of policy analysis and formulation still rests with those to whom man is man and institutions are institutions and who think of policy as a reshuffling of the same old variables. One of Franklin Roosevelt’s great skills as a political leader was his encouragement of new techniques, as illustrated by the National Recovery Administration, the National Labor Relations Board, Lend-Lease, food stamps, and the fifty-destroyer transaction. A contrast was the futile debate during the Second World War over the union shop in American industry, a debate in which many groups refused to consider any new alternatives to the open shop, closed shop, and union shop, although in the War Labor Board the debate finally came to an end with the innovation of the maintenance-of-membership technique. Similarly, one finds in the British debate over broadcasting policy a preoccupation with the British system and American commercial radio as the only two major alternatives; all too seldom attention is given to other alternatives yet to be tried and to still others unknown, yet to be invented. An old saw says that armies are always well prepared to fight the last war. Much of the discussion of social policy suffers from the same disability.

SELECTIVITY IN POLITICO-ECONOMIC TECHNIQUES. The alternative techniques available for a particular problem commonly offer a high degree of selectivity. They permit more precision in choice, more careful adaptation of means to ends, than men sometimes take account of. Consider, for example, the fine gradations in choice of alternative schemes of private enterprise permitted by its multiplicity of forms, existing and conceivable. The refinements in choice permitted by gradations in techniques are not limited to trivial differences among them. They range over a number of continua in which the opposite poles pose such critical alternatives as government power and private power, voluntarism and compulsion, centralization and decentralization, prescription and indoctrination, local determination and national determination.

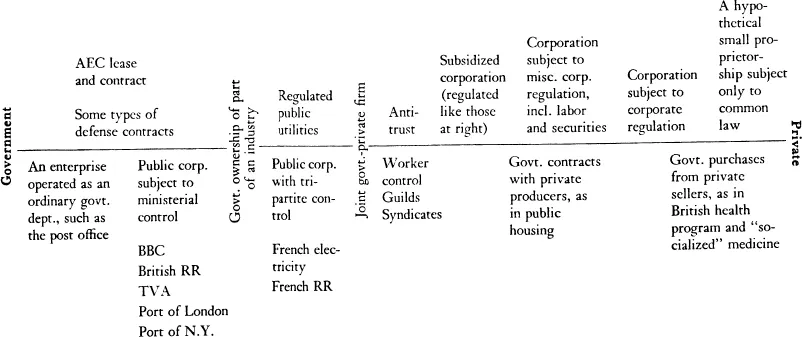

We can illustrate the array of choices commonly available to policy, each one slightly different from another related to it, and at the same time emphasize once more the large numbers of alternative techniques by diagraming a number of these continua in which the variables are significant and upon which particular techniques suited to some particular problem or goal can be placed. Imagine, for example, the choices open between private ownership and public ownership as polar methods of enterprise organization. Opinions will differ, of course, as to the exact placement of some techniques on such a scale; but despite these differences, the pattern of such a continuum is as in Diagram 1.

The diagram proves nothing; it is only illustrative. Diagram 1 displays something of the variety of techniques possible between an unregulated private enterprise, on the one hand, and a business like the post office run as an ordinary government department, on the other hand. Both to illustrate how “public” ownership and “private” ownership have been stretched in meaning to cover techniques ranging over a long continuum and to show again the invalidity of thinking in terms of comprehensive systems, we have placed the techniques ordinarily associated in the public mind with private enterprise above the line and those commonly associated with socialism below. They overlap; the one set of techniques is not huddled toward one end of the scale, the second set toward the other. Note in particular the placement of “socialized” medicine.

DIAGRAM 1. A Continuum Showing Some of the Choices Available Between Government Ownership and Private Enterprise

Below the line: techniques popularly described with words such as “nationalized,” “socialized,” “government owned,” and “public enterprise.”

Above the line: techniques popularly described with words such as “private enterprise,” “private property,” and “free enter...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Preface 1976

- Preface 1953

- Acknowledgments

- Part I. INDIVIDUAL GOALS AND SOCIAL ACTION

- Part II. TWO BASIC KINDS OF SOCIAL PROCESSES

- Part III. SOCIAL PROCESSES FOR ECONOMIZING

- Part IV. FOUR CENTRAL SOCIOPOLITICAL PROCESSES

- Part V. POLITICO-ECONOMIC TECHNIQUES

- POSTSCRIPT

- Index