- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cognitive Responses in Persuasion

About this book

First published in 1982. This collaborative product of leading contributors seeks to update information on the psychology of attitudes, attitude change, and persuasion. Social psychologists have invested almost exclusively in the strategies of theory-testing in the laboratory in contrast with qualitative or clinical observation, and the present book both exemplifies and reaps the products of this mainstream tradition of experimental social psychology. It represents experimental social psychology at its best. It does not try to establish contact with the content-oriented strategies of survey research, which have developed in regrettable independence of the laboratory study of persuasion processes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

Historical and Methodological Perspectives in the Analysis of Cognitive Responses: an Introduction

Timothy C. Brock

Ohio State University

Ohio State University

It has been almost half a century since Gordon Allport (1935) wrote that "attitude is probably the most distinctive and indispensable concept in contemporary social psychology [p. 798]." A quick perusal of the contents of any current text in social psychology will reveal that more attention is devoted to the topic of attitudes and persuasion than to any other area. Social psychologists have emphasized the empirical investigation of attitudes because of the directing role attitudes play in determining social behaviors. Other disciplines are interested in the study of attitudes and persuasion because of its direct practical relevance for understanding and predicting such phenomena as consumer behavior, the effectiveness of advertising campaigns, the results of political elections, jury decisions, psychotherapy outcomes, and so forth.

This volume is an advanced undergraduate/introductory graduate textbook dealing with attitude change from the perspective of mediating and accompanying cognitive responses. Cognitive response analysis, the volume's unifying theme, stems from the long-standing and widespread interest in elucidating the fundamental cognitive processes that are instigated by a persuasive message. In his excellent chapter on attitudes and persuasion in The Handbook of Social Psychology, McGuire (1969a) proposed that two schools of research techniques and interests have emerged—the "Hovlanders' (from Carl Hovland, who began the first systematic persuasion experiments during World War II and later at Yale) and the "Festingerians" (named after Leon Festinger, the originator of the influential theory of cognitive dissonance). Despite the many differences between these schools noted by McGuire, one point of substantial agreement is that attitude change can best be explained by taking into account the mental processes that ensue once a persuasive stimulus has impinged upon a thinking recipient (cf. Festinger & Maccoby, 1964; Hovland, Lumsdaine, & Sheffield, 1949). The authors who have contributed to this volume share the view that people are active processors of the information they receive.

Despite the heavy explanatory roles cognitive mediating responses have been assumed to play in producing persuasion, the traditional foci of attitude change texts have been on presenting diverse theories of attitude change or on encyclopedic renditions of empirical findings. Analyses of the cognitive processes that underlie attitude changes have been relatively ignored. In fact, it is only within the past decade that the implications of an information-processing view have been carefully applied to the study of persuasion. In that short period of time, however, techniques for the measurement of mediating cognitive responses have been developed, and the information-processing approach has shown its ability to integrate a wide body of existing data under one conceptual framework, to provide insights into the microprocesses involved in persuasion, and to generate unique and nonobvious predictions. This volume highlights the past decade of research and theory on cognitive responses in persuasion.

The goal of Part I of this book is to provide an introduction to the cognitive response approach to the study of persuasion. In Chapter 1, the editors present a brief history of the attitude concept and the cognitive response approach to persuasion. The cognitive response approach is compared to the four traditional approaches to persuasion (learning, functional, perceptual, and consistency), and the classic early research findings that documented the importance of cognitive processes for understanding attitude change are cited. In Chapter 2, Cacioppo, Harkins, and Petty give the concepts of attitude and cognitive response a precise meaning and popular techniques for the measurement of these internal constructs are presented.

Most of the knowledge that psychologists have about attitude change processes comes from experimental research. In Chapter 3, Petty and Brock introduce the experimental method and show how a hypothesis about the importance of a person's thoughts in producing persuasion can be tested and validated. In Chapter 4, Cacioppo and Sandman relate attitudes and cognitive responses to physiological responses. Physiological techniques for the measurement of attitudes and cognitive processes are discussed, and a model that relates attitudes and cognitive responses to bodily processes is presented.

Chapter 5, by Miller and Colman, presents a critical evaluation of the cognitive response approach to persuasion. Methodological and conceptual problems in analyzing the cognitive mediation of persuasion are addressed, and various remedial recommendations are made. Greenwald, in Chapter 6, evaluates the direction that research on cognitive responses has taken since he first introduced the term in 1968 and speculates about some future gains of continued use of the approach. Both Chapters 5 and 6 are somewhat more technical than the preceding four chapters and may be of interest primarily to graduate students and researchers in the field. Other readers may wish to omit these chapters and proceed directly to Part II, which presents a cognitive response analysis of the major research findings on persuasion.

1

Historical Foundations of the Cognitive Response Approach to Attitudes and Persuasion

Richard E. Petty

University of Missouri-Columbia

Thomas M. Ostrom

Timothy C. Brock

Ohio State University

University of Missouri-Columbia

Thomas M. Ostrom

Timothy C. Brock

Ohio State University

Introduction

How do you feel about sentencing criminals to the electric chair? Is the death penalty a positive weapon against crime? A necessary evil? A disgusting anachronism? How would you describe your attitude? What would make you change your mind? This book explores the cognitive processes involved in attitude change. Let's say that you and three friends have been asked how you feel about capital punishment by a national opinion-polling organization. Each of your friends indicates on an attitude scale (the one shown in Table 1.1 is typical of those used in attitude research) that he or she feels "somewhat unfavorable." What does this tell you about their attitudes? Should you assume that each person has the same attitude? What roles do their attitudes play in their lives? How could you persuade them to change their attitudes?

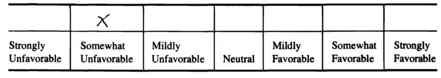

TABLE 1.1

Sample Attitude Scale Response to the Issue: Capital Punishment

Sample Attitude Scale Response to the Issue: Capital Punishment

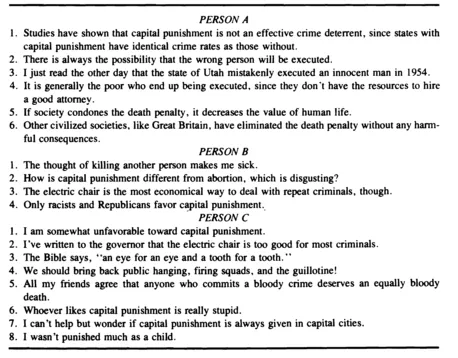

Even though the attitudes of your friends came out the same on the scale, their attitudes are probably not identical. You'd find this out if you asked them to talk about their attitudes toward the electric chair. During the conversation you could probably list several thoughts they would express. Table 1.2 presents some thoughts from three different persons. Person A appears to be unfavorable because she opposes the death penalty in general and can give reasoned arguments to support that position. Person C, on the other hand, feels that the electric chair is not severe enough. Person B has mixed feelings, but his emotional responses against the death penalty carry the greatest weight.

Although each person's response is identical on the attitude scale, the thoughts behind the ratings are different. Some responses are emotional; others are rational. Some attack persons who support capital punishment; others attack arguments that might be used to support the concept. Some responses seem consistent with each other; others appear contradictory. Some are elaborations of previous thoughts; others are specifications. Some relate the attitude to other attitudes; others relate it to friendships and social relationships. Some are almost identical to the attitude scale statement; others are zany, illogical, or unrelated to the attitude scale statement.

TABLE 1.2

Cognitive Responses to the Issue: Capital Punishment

Cognitive Responses to the Issue: Capital Punishment

The particular focus of this text is on the thoughts behind attitudes. We emphasize thought mechanisms to explain the process of persuasion, or how people change other people's minds. An understanding of the effectiveness of persuasive communications depends on an understanding of the cognitive responses that arise in the persuasion context. By a cognitive response to a communication, we mean to include all of the thoughts that pass through a person's mind while he or she anticipates a communication, listens to a communication, or reflects on a communication. If we presented each of your three friends with a Supreme Court opinion arguing in favor of the death penalty, we would want to know his or her thoughts during and following examination of the court opinion, each individual's cognitive reactions. Merely manipulating experimentally features of the persuasion setting (for example, the trustworthiness of the source) or measuring responses on rating scales is not an adequate research technique to assess the dynamics of how an attitude is changed. Yet this is the primary strategy researchers have used during the past 30 years to test theories of attitude change. The validity of the theory being tested, even theories about the thoughts people have in response to communications, was determined primarily by whether or not the theory could accurately predict how the attitude scales would be affected. The thoughts that accompanied the attitude were typically not measured. In this chapter we review research on cognitive responses to persuasion from World War II to the mid-1960s. The following chapters bring us to the present. But first, let us turn to a history of the concept of attitude. The term has not always meant what we think of today.

A Brief History of the Attitude Concept1

The word attitude first came into English about 1710 from the French attitude, which came from the Italian attitudine, which in turn came from the Latin aptus, meaning "fitness" or "adaptedness." In the 18th century the term was used primarily to refer to the posture or bodily position of a statue or figure in a painting. The word today, of course, still refers to a general orientation toward something (like your orientation toward, or view of, the death penalty).

Although the sociologist Herbert Spencer employed the term as a mental concept (e.g., having the "right" attitude) in his First Principles in 1862, a more influential usage occurred in Charles Darwin's Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals in 1872. Darwin used attitude as a motor concept—the physical expression of an emotion (e.g., a scowling face signifying a "hostile attitude"). To Darwin, an attitude was a biological mobilization to respond. In 1888 the experimental psychologist L. Lange discovered in a reaction-time experiment that subjects who were consciously prepared to press a telegraph key to a signal reacted more quickly than subjects whose primary attention was focused on the incoming signal rather than the response. He called this reaction a "task-attitude" or aufgabe. To Lange, the task-attitude was a musculature preparation to respond (e.g., an "alert attitude"). The English neurophysiologist, Charles Sherrington referred (1906) to attitude, not as the occasional manifestation of a strong emotion or a certain task set, but as one's normal pose or posture (e.g., an "upright attitude"). Although Darwin, Lange, and Sherrington viewed attitudes as motor states, the mental (or cognitive) view was destined to take prominence.

The first indication of this came from the German Würzburg school of psychology, whose mentors included Kiilpe, Wiindt, Titchener, Watt, and Ach. The aim of this school was to study the phenomenon of thought—a traditional theme handed down from the ancient Greeks. The Wurzburg school regarded an attitude as a task set, as did Lange; but instead of focusing on the motor aspect, they focused on the mental, or abstract, and logical aspects. As a result of the Wurzburg work, most psychologists came to accept "attitude" as an indispensable concept, though not all believed attitudes to be reducible to purely mental events.

Margaret Washburn (1916), Titehener's first doctoral student, tried to combine both the mental and motor conceptions of attitude. In Movement and Mental Imagery, she proposed that all intellectual processes were accompanied by motor impulses, however slight (i.e., mental work was physical). Washburn's book strengthened the association of attitude with mental activities without diminishing the motor aspect. At about the same time, John B. Watson (1919), the founder of the behaviorist school of psychology, was arguing that all thinking could in principle be correlated with movements of the larynx (and emotions with tremors of the genitals). Chapter 4 in this book presents some current thinking about the relations among physiological activity, mental processes, and attitudes.

The mental view of attitudes was given a large boost in 1918 with the publishing of a landmark in social research, The Polish Peasant in Europe and America, a study of the problems Polish immigrants faced in coming to the United States. A key concept in this work (1927 edition) by sociologist William I. Thomas and poet-philosopher Florian Znaniecki was attitude, which they defined as "a process of individual consciousness which determines real or possible activity of the individual in the social world [p. 22]." For Thomas and Znaniecki, an attitude was always a feeling directed toward some object. Thus "love of children," "hatred of criminals," and "respect for science" were possible attitudes. This view of attitude was important historically not only because attitudes had acquired an "object" but also because Thomas and Znaniecki had stripped attitude of its physiological content. This non-physiological, more cognitive view of attitude became acceptable to psychologists in large part because the influential psychologists of the 1930s (e.g., Hull, Tolman, Skinner) were neo-behaviorists who postulated nothing about physiology. Also, during the mid-thirties and in the years beyond, researchers began to explore the similarities between attitude and psychophysical judgments—the earliest area of mental investigation in experimental psychology (e.g., Sherif, 1935; Sherif & Cantril 1945, 1946; Tresselt & Volkmann, 1942).

At the same time, however, by making attitudes less physiological and more cognitive, Thomas and Znaniecki removed the part that made attitudes observable. The concept of attitude would surely decline in empirical science if it were not measurable. Fortunately, theory and techniques for the measurement of attitudes were soon developed by L. L. Thurstone (1928), a University of Chicago psychologist whose primary interest had been in psychophysics, and by Rensis Likert (1932), a statistician with the U. S. Department of Agriculture. Both Thurstone and Likert introduced direct methods of measuring the pro-con or evaluative property of attitudes. These techniques were soon followed by others, including Moreno's sociometric choices in 1934, Guttman's cumulative scaling method in 1941, Coombs' unfolding technique in 1952, and Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum's semantic differential in 1957. The popular techniques for measuring attitudes are presented in the next chapter.

The first notable effort to achieve a significant sampling of public attitudes on a variety of topics appeared in 1929 in Robert and Helen Lynd's Middletown, an in-depth discussion of life in Muncie, Indiana, which became the first sociological best-seller. Public awareness of attitude surveys increased in 1936, when the now defunct Literary Digest attempted to predict, through a nationwide postcard poll, the winner of the presidential election (they failed miserably, however, because their sample of affluent respondents contained a much higher percentage of Republicans than appeared in the electorate). By World War II, the cognitive conception of attitude was well entrenched in American scientific and lay vocabularies.

Traditional Approaches to the Study of Persuasion

Once the concept of attitude was firmly established, attention turned to the interesting question of attitude change. Although the first known set of principles governing the art of persuasion was recorded ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- PART I: HISTORICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES IN THE ANALYSIS OF COGNITIVE RESPONSES: AN INTRODUCTION

- PART II: THE ROLE OF COGNITIVE RESPONSES IN ATTITUDE CHANGE PROCESSES

- PART III: THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES IN THE ANALYSIS OF COGNITIVE RESPONSES

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cognitive Responses in Persuasion by Richard Petty,T. M. Ostrom,T. C. Brock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.