This is a test

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Family History and Local History in England

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is a book for those thousands of family historians who have already made some progress in tracing their family tree and have become interested in the places where their ancestors lived, worked and raised children. It emphasises the diversity and extraordinary complexity of the rural and urban communities in provincial England even before the great changes associated with the Industrial Revolution.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Family History and Local History in England by David Hey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter One

The Middle Ages

The family historian naturally works backwards from present generations into the remote past. All his early research is concentrated upon the twentieth and nineteenth centuries as he proceeds steadily back in time, proving one link after another in his chain of evidence. The Middle Ages are not his immediate concern and indeed he may never be able to trace his ancestors back that far. It was my original intention to write the book in the same way, but I soon found that the whole flow of the writing was in the opposite direction; the story of population change is one of growth, the account of industrial communities is one of increasing complexity, rural parishes and provincial towns altered in many subtle ways as the centuries passed. It became clear that the book had to proceed chronologically if it was to preserve its unity and not become hopelessly fragmented. So the chapter on the Middle Ages sets the scene and emphasises that even in the earliest periods for which we have evidence our ancestors were much more mobile than we once thought. Later chapters will become fuller as the evidence swells and as we approach the periods that are of greatest interest for most family historians, but a synopsis of the major studies of medieval communities will help our understanding of later eras and an account of recent work on surnames should appeal to all family historians who are interested in the ultimate quest for origins. This chapter forms an essential part of my argument that at its best the study of family history should be concerned with broad issues covering all periods of time for which we have evidence.

Population and the Economy

The family historian who tries to trace his ancestors back beyond the Elizabethan period is normally faced with grave problems of identification. For the period before parish registers were kept and before ordinary families began to adopt the practice of making a will, one has to turn principally to manorial court rolls and government taxation records. These sources do not give explicit genealogical data; it is unusual to get a good run of early court rolls and one can rarely proceed with confidence beyond the richer sections of society. But even if a direct line cannot be proved, the family historian can often point to probabilities and sometimes to the likely origin of a surname. The detailed local knowledge that comes not only from documents but from the study of places on the ground and from large-scale ordnance survey maps is as essential for a family historian dealing with the Middle Ages as it is for later periods. A background knowledge of medieval population trends and the structure of rural and urban societies is also necessary if one is to tread sure-footedly in an area beset with pitfalls for the unwary.

At the time of the great Domesday Survey of 1086 England's population stood somewhere between 1.5 and 2.25 millions. This figure is tiny in comparison with today's level, nevertheless a very high proportion of our present settlements were already in existence and had been so from time immemorial. During the two and half centuries after the Norman Conquest the national population grew quite rapidly, so that by the year 1300 it had at least doubled and may perhaps have trebled. At a minimum it had reached 3.25 millions and probably was much higher. Throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries existing settlements had expanded, new towns had been created and many new farmsteads and hamlets had been established on the edges of moors, woods and fens. These new, isolated settlements frequently gave rise to family names, a prolific group known as locative surnames.

By 1300 many families were living on the margin of subsistence. Medieval England was primarily an agricultural country; everywhere the growing of corn was a basic preoccupation. In later times those areas with a harsh climate and poor, thin soils turned increasingly to pastoral farming and to rural crafts which provided the wealth that enabled them to import their corn from more favoured areas. They were able to do this to a limited extent in the early Middle Ages, but agricultural yields were low and the growing pressure on available resources meant hardship and ultimately disaster. By 1300 smallholders with little to fall back upon in times of crisis amounted to at least 1.5 million people and perhaps as many as 2.5 millions; they formed an increasingly high percentage of rural society. Everywhere in England the basic pattern was one of small, family farms. Some families with sufficient land to survive remained rooted in one spot, but in general the Middle Ages was just as remarkable as later periods for the amount of movement from place to place. Mobility was usually restricted to a few miles within a well-defined neighbourhood, but the new towns that were founded during this period were often a magnet for migrants from much further afield. The family historian is well-advised not to place too much reliance on textbooks that stress that serfs were legally tied to the manor, but to study instead recent work on the origins and ramifications of surnames and detailed studies of particular manors. In practice, medieval people appear to have been just as mobile as were their sixteenth and seventeenth century descendants.

By 1300 most of the country's available agricultural land was being farmed, even on those soils that were of little value. Given the primitive technology of the time, the expanding population had no alternative but to spread on to the moors and into the woods and marshes. A crisis point was reached long before the Black Death of 1348-49. Historians are now well aware of the impact of the series of harvest failures and livestock disasters that befell many parts of the country between 1315 and 1322 and which checked, if it did not reverse, population growth. The Black Death was the major catastrophe, which reduced the population by between a third and a half, but the fourteenth century witnessed recurrent plagues and other epidemics. Some places suffered heavy mortalities in the major visitations of 1361-62 and 1375. Bubonic plague remained endemic throughout the Middle Ages and other diseases were also virulent. Throughout England population levels fell considerably and marginal land reverted to its former waste condition. Estimates of national population figures for the later Middle Ages vary considerably because we have few firm statistics to guide us, but by 1500 the country may have had only half the number of people that it had supported in 1300.

Those families which survived these recurrent disasters found themselves in a far stronger position than they had been in at the beginning of the fourteenth century. The poorer sections of society benefited because more land was available for all and because wage levels rose as demand outran supply. The richer families also fared well. During the later Middle Ages an energetic farmer with an eye to the main chance was able to enlarge his estate and rise to the status of yeoman or minor gentleman; many of the farming dynasties of England were founded during this period. The average size of holdings of all classes of rural society increased and for the great majority of those rural families which had come through the terrible experiences of the fourteenth century a better standard of living was the reward.

Cuxham and Wigston

The family historian who wants to gain some understanding of life on the rural manor during the Middle Ages should first of all consult two classic local studies: Professor P.D.A. Harvey's A Medieval Oxfordshire Village: Cuxham 1240 to 1400 (1965) and Professor W.G. Hoskins's The Midland Peasant: The Economic and Social History of a Leicestershire Village (1957), the story of Wigston from its origins to the end of the nineteenth century. The small parish of Cuxham is situated between the Chilterns and the river Thame and is less than a square mile in extent. Its woodland had all been cleared by the time of the Domesday Survey, when the area under the plough was already as extensive as it was to be in the fourteenth century. Cuxham's three open-fields retained their simple medieval descriptions of North, South and West until their enclosure in 1846-47. During the Middle Ages the local farmers followed a simple, three-course rotation of spring corn, winter corn and fallow. According to the Oxfordshire Hundred Rolls of 1279 only two Cuxham families were freeholders; the other twenty-one were either unfree peasants or cottagers. The immediate effects of the Black Death, which struck the village in the winter and spring of 1349, were severe. None of the twelve villeins recorded in the manorial court rolls in January 1349 was still there at the end of the year, and only four of the eight cottagers remained in the village in 1352. Three years after the plague had gone many properties still lay vacant, but by May 1355 new tenants seem to have been found for all of them. The local population had been partly replenished from outside. Nevertheless, nearly three decades after the visitation the 1377 poll tax returns list only thirty-eight inhabitants over 14 years old, that is a third of Cuxham's estimated population in 1348.

At the conclusion of his study Professor Harvey warns that in his experience little information obtained from manorial records can be safely taken at face value and that one cannot argue from omissions. The family historian treads on dangerous ground when he ventures into this area. Nevertheless, there is much to be gleaned even from such unpromising territory. For example, Cuxham's manorial records shed some interesting light on surname development. In general, children of manorial tenants started in life bearing their father's usual surname, but in two cases a name taken from the mother's Christian name was used as an alternative, and more often an occupational name eventually replaced the original one. A greater problem for the family historian is posed by the arrangement whereby if a man entered a tenement through marrying a widow, he normally assumed the surname of her first husband. For instance, when Robert Waldrugge married Agnes, the widow of Robert Oldman, in 1296 he became the second Robert Oldman to farm that propefty. If it had not been established that the first Robert Oldman had died in 1296 it could have been reasonably assumed that he was the Robert Oldman who became reeve in 1311, whereas in fact the reeve was the Robert Waldrugge who had changed his name. At this period surnames were still in a state of flux; fortunately for the family historian most of them soon became stable.

The Leicestershire village of Wigston was also farmed on an open-field system until the era of parliamentary enclosure, but it was always far more populous than Cuxham and it contained a large and persistent class of small freeholders who had considerable independence from the absentee lords of the manor. At the time of the Domesday Survey two out of every five Wigston peasants were free. Wigston was the largest village in Leicestershire in 1086, and though it declined considerably for a time after the Black Death it retained this position throughout most of the succeeding centuries. By the Tudor period most of the unfree peasants were copyholders of inheritance, in other words they had the right to pass on their landed property to their successor, subject only to a small payment or fine on entry and a small annual rent thereafter. Both the fines and the rents were certain and could not be altered at the will of the lord. In inflationary periods this arrangement benefited the tenants considerably. Early fourteenth century tax returns show that Wigston already had a class of larger and comparatively wealthy farmers, for nearly 70 per cent of the tax was contributed by only 10 of the 120 or more families in the village. Throughout the Middle Ages local farmers continually bought and sold land, mostly in very small parcels. The impression gained from the records is of a vigorous, thriving free peasantry and of economic inequality. In Wigston the inheritance system was primogeniture; although provision was often made for a widow, younger sons and unmarried daughters this was almost invariably in the form of a life interest only so that the ancestral tenement passed to the eldest son unimpaired in size. Younger sons became craftsmen and labourers.

During the fifteenth century some old Wigston families disappeared, but in Professor Hoskins's words, 'a solid core of middling peasant freeholders lasted right through this century of change and movement'. Such families had sufficient land to survive but insufficient resources to move out of the parish to larger farms. In general, it was the wealthiest and the poorest families which left the village. The Astills, Smiths, Herricks, Palmers, Simons, Moulds, Stantons and Clays, and possibly the Shepherds and Cooks remained in Wigston from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, but they formed only a small proportion of the whole community. Hoskins has estimated that only about 10 per cent of the Leicestershire families recorded in the 1524-25 lay subsidies had persisted in the same place since the poll tax returns of 1377-81. The fifteenth century had seen a great reshuffle of the local population.

By the reign of Henry VIII a quite disproportionate share of property in scores of Leicestershire villages was held by one, two or three families who had managed to build up sizeable estates over the last 100-150 years. In this respect the differences between neighbouring communities was sometimes marked. Immediately south of Wigston the villages of Foston and Wistow shrank until only a hall and a church were left and sheep and cattle grazed the ridges and furrows of the former open-fields and the mounds and hollows that marked the sites of houses. In Wigston, however, life went on with a 'monumental stability'. There, the 1524 subsidy returns reveal:

a solid community of middling-sized farmers, small yeomen and husbandmen, with no overshadowing yeoman family at the top, dominating the place as the Bents did at Cosby, the Bradgates at Peatling Parva, the Hartopps at Burton Lazars and the Chamberlains at Newton Harcourt and Kilby, to cite a few outstanding examples out of many from Leicestershire records.

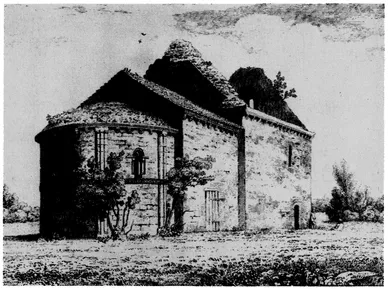

Plate 1.2 Steetley Church, Derbyshire This north-east view of the church was published in the Derbyshire volume of Daniel and Samuel Lysons, Magna Brittania, V (1817). It shows the church abandoned and forlorn, the entire roof of the nave having collapsed. Steetley was a deserted medieval village, a chapel of ease in the parish of Whitwell, and its church had become redundant.

However, sufficient remained to show that it had been a fine example of a small Norman church consisting of a nave, chancel and vaulted apse. Carved heads formed a corbel table all round the church and the apse retained its pilasters, decorated string course and splayed windows. On the other side of the church is a beautifully-carved Norman door, which leads into a memorable interior. It is not known who was responsible for erecting such a lavishly decorated building. Pevsner writes: 'There are few Norman churches in England so consistently made into showpieces by those who designed them and those who paid for them.' The church was splendidly restored by the Victorian architect J. L. Pearson in 1876-80.

Even in the Middle Ages the local history of one parish could be very different from that of its neighbours.

Halesowen

The studies of Cuxham and Wigston were made before historians developed the techniques of family reconstitution in order to obtain fuller demographic information. These techniques were first used to extract data from parish registers but they have recently been applied to medieval manorial court rolls in Zvi Razi's study of Life, Marriage and Death in a Medieval Parish: Economy, Society and Demography in Halesowen, 1270-1400 (1980). This book is not only of great interest to economic historians who are concerned with population trends and structural changes in the fourteenth century but is one that every family historian who wishes to extend his researches back into the Middle Ages should read. It triumphantly demonstrates that a great deal of reliable genealogical information can be obtained from a good run of manorial court rolls. Halesowen is unusually fortunate in having such a complete set, for in many places none survives at all, but Razi has shown that where manors are richly documented the local and family historian can proceed cautiously but accurately, providing of course that he has a working knowledge of medieval palaeography. Dr Razi concludes that the range of activities recorded in surviving rolls is so wide that a villager could hardly avoid appearing before his manor court from time to time. He believes that the adult male population of Halesowen is almost totally represented in the surviving documents.

Halesowen was a large manor with a small market centre and scattered settlements in twelve rural townships to the west of Birmingham. The manor was 8 miles long and up to 2½ miles broad and covered about 10,000 acres. For the period 1270-1400 there are 215 surviving rolls covering 1,667 sessions of the court; the rolls of only 16 years are missing. With such a good sequence of detailed records positive identification of individuals is possible. Some people appear only once or twice but 80 per cent of the recorded names appear more than 10 times and certain individuals are recorded over 200 times. Each of the 5,002 names noted in the Halesowen court rolls between 1270 and 1400 is mentioned on average 15 times.

Even so, the historian is faced with severe problems of correct identification. First of all, as peasant surnames were unstable before the mid fourteenth-century villagers appear in the rolls under more than one name and often under two. Dr Razi writes:

They were named indiscriminately by the scribes according to occupation or function, township, locality, place of origin and family relationship. For example, Alexander, a villager from the township of Romsley, who appears in the records between 1274 and 1293, lived in the small hamlet of Kenelmestowe near the Church of St Kenelm and was a clerk by profession. He therefore had three surnames - 'de Kenelmestowe', 'de St Kenelm' and 'the Clerk'. His son Clements was called 'Clements the son of Alexandra of St Kenelm' and 'Clements Tandi'. But in 1293 Clements married Emma de Folfen and entered with her the family holding. Henceforward he appears in the court rolls as 'Clements de Folfen'.

After the Black Death surnames stabilized and few villagers had aliases.

A second problem - one that the genealogist will be familiar with in later periods -...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Middle Ages

- Chapter Two: Early-modern England

- Chapter Three: Late-Georgian and Victorian England

- Chapter Four: Excursions into family and local history

- Further reading

- Index