![]()

Chapter One

Entertainment-Education

For the past ten years I had lost my way but Tinka Tinka Sukh showed me a new path of life. … I used to be delinquent, aimless, and a bully. I harassed girls … one girl reported me to the police and I was sent to prison. I came home unreformed. One day I heard a program on radio. … After listening to the drama, my life underwent a change. …I started to listen regularly to All India Radio [AIR]. … One day I learned that Tinka Tinka Sukh, a radio soap opera, will be broadcast from AIR, Delhi. I waited expectantly. Once I started listening to the radio program, all my other drawbacks and negative values were transformed.

—Birendra Singh Khushwaha

(a tailor in the Indian village of Lutsaan)

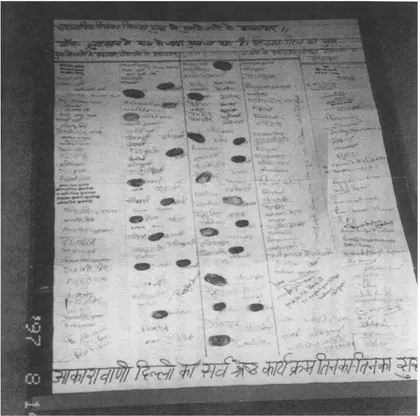

In December 1996, a colorful 21 × 27 inch poster–letter–manifesto, initiated by a village tailor (quoted above) with the signatures and thumbprints of 184 villagers, was mailed to All India Radio (AIR) in New Delhi, then broadcasting an entertainment-education soap opera Tinka Tinka Sukh (Happiness Lies in Small Things). The poster-letter came from a village named Lutsaan in India’s Uttar Pradesh State. It stated: “Listening to Tinka Tinka Sukh has benefited all listeners of our village, especially the women. … Listeners of our village now actively oppose the practice of dowry—they neither give nor receive dowry.” This unusual letter was forwarded to us by Usha Bhasin, the radio program’s director and executive producer at AIR.

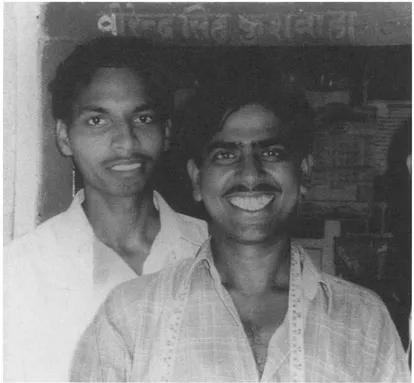

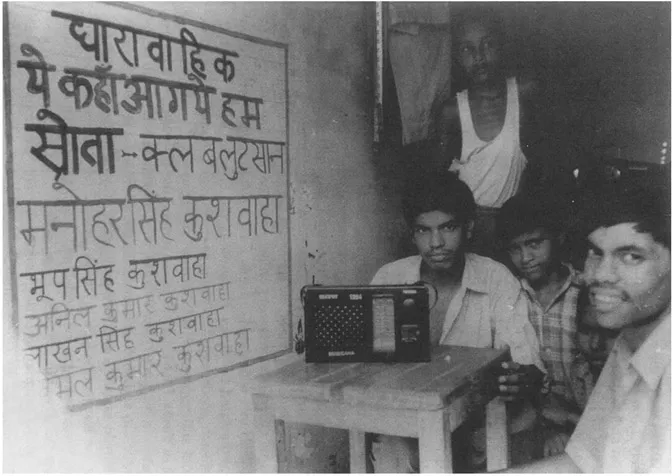

We were intrigued and visited the village. The poster-letter suggested that strong effects of Tinka Tinka Sukh had occurred in this village (see Photos 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3). We wondered whether the villagers had been able to actually change dowry behavior, a practice deeply ingrained in Indian culture.

Photo 1.1. The poster-letter from Lutsaan, including the signatures and thumbprints of 184 community members, pledging not to give or accept dowry. (Source: Personal files of the authors.)

Photo 1.2. Birendra Singh Khushwaha, the tailor in Village Lutsaan who initiated the poster-letter. (Source: Personal files of the authors.)

Photo 1.3. A hand-painted sign in Village Lutsaan in July 1998 promoting Yeh Kahan Aa Gaye Hum (Where Have We Arrived?), the successor radio soap opera about the environment following Tinka Tinka Sukh. The sign lists some members of the newly formed radio listeners’ club, established since the first visit of our research team to Lutsaan in August 1997. (Source: Personal files of the authors.)

We thought that the study of these effects in Lutsaan might enhance understanding of the process through which entertainment can change audience behavior. Some months later, in August 1997, when we approached Lutsaan on the road from Aligarh, the nearest city, we noticed that the village rises some 90 feet above the surrounding Gangetic Plain. Most of the village’s approximately 1,000 homes are located on the sides of a small hillock, topped by an ancient fort. The adobe homes neighbor in a dense manner. The population of Lutsaan is about 6,000. A few homes, including those of the pradhan (village chief) and the tailor, are located on the main road, a short distance from the village center. Numerous narrow paths meander among the mud houses. Buffalo are everywhere, and the smell of dung pervades the village. Fertile, flat fields surround Lutsaan, and its farmers travel out to work on them each day.

On arriving in the village, we met first with the pradhan, who described the village as relatively well-off, with 60 radios, 5 television sets, and 10 tractors. Nearly every household owns a bicycle and 25 households possess a motorcycle. Lutsaan has two village schools that offer 8 years of education. The ratio of boys to girls in these schools was 90:10, but changed to about 60:40 in the past year, in part due to the effects of Tinka Tinka Sukh.

The village has a Shyam Club (named after the Hindu God Krishna) with about 50 active members. It carries out various self-development activities, including village clean-up, fixing broken waterpumps, and reducing religious and caste tensions in the village. The village postmaster, Om Prakash Sharma (called Bapu, or respected father, by the villagers) is chair of the Club. He told us that when an interpersonal conflict occurred recently, members of the Shyam Club met with the disputants until a solution was mediated. In 1996–1997, stimulated by Tinka Tinka Sukh, the Shyam Club devoted its attention to such gender equality issues as encouraging female children to attend school and opposing child marriage and dowry.

The plot of Tinka Tinka Sukh centered around the daily lives of a dozen main characters in Navgaon (New Village), who provided positive and negative role models to audience individuals for the educational issues of family planning, female equality, and HIV prevention. Shyam Club members reported that the Navgaon village in Tinka Tinka Sukh was much like their own village, progressive yet traditional, and with a cast of characters much like the ones portrayed in the radio soap opera.

Listeners to the program in Lutsaan said they were “emotionally stirred” by Poonam’s character in Tinka Tinka Sukh. Poonam, a young bride, is beaten and verbally abused by her husband and in-laws for not providing an adequate dowry, the payment by a bride’s parents to the groom’s parents, in whose home she lives after marriage. In recent decades, dowry payments in India became exorbitant, usually including cash or gold, a television set, or a refrigerator. If dowry payments are inadequate, the bride may by mistreated by the husband’s family. In extreme cases, the bride is burned to death in a kitchen accident, called a dowry death. In the radio soap opera, Poonam was humiliated and sent back to her parents after incorrectly being accused by her in-laws of infidelity to her husband. In desperation, she commits suicide. Lutsaan’s poster-letter noted:

It is a curse that for the sake of dowry, innocent women are compelled to commit suicide. Worse still. … women are murdered for not bringing dowry. The education we got from Tinka Tinka Sukh, particularly on dowry is significant. … People who think differently about dowry will be reformed; those who practice dowry will see the right way and why they must change.

Tinka Tinka Sukh also opposed child marriage. In the soap opera, Kusum is married before the legal age of 18, impregnated, and dies in childbirth. Although child marriage is illegal, it is common in Indian villages. Equal opportunity for girls is stressed in the radio soap opera. The poster-letter stated:

In comparison with boys, education of girls is given less importance. Even if some girls wish to develop themselves through their own efforts and assert their individuality, their family is not supportive. … Whenever girls were given equal opportunities for educating themselves, they have done as well as the boys.

Family planning/population size issues were stressed in Tinka Tinka Sukh. The poster-letter stated: “Our society has to take a new turn in their thinking concerning family size. As the cost of living rises, having more children than one can afford is inviting trouble. … This message of Tinka Tinka Sukh comes across very clearly.”

Both individual and collective efficacy were emphasized in the radio soap opera. After being left by her husband, a young bride, Sushma, takes charge of her life by starting a sewing school. She is rewarded in the storyline for this efficacious behavior. Efficacy is also demonstrated by Sunder, a drug abuser, who gets clean and then obtains a job. Ramlal, a pampered son and male chauvinist, represented a negative role model in the early episodes of Tinka Tinka Sukh. Later, he becomes a development officer, leading Navgaon village in a variety of progressive activities. The tailor in Lutsaan identified with this transitional role model, as he stated in the poster-letter: “I saw myself, in fact many of my antisocial ways, reflected in Ramlal who is also reformed.” Such parasocial involvement with a transitional role model is one way in which entertainment-education affects behavior change.

Collective efficacy is also stressed in Tinka Tinka Sukh, as Navgaon village displays collaborative spirit in solving its problems. For example, villagers construct a new hospital, reject government assistance, and raise the needed funding themselves. As the poster-letter stated: “The problems of the village are tackled collectively, and in the event of any major problem, the matter is put before the panchayat [village council] for resolution.”

The Tailor and the Postmaster

One reason for the relatively strong effects of Tinka Tinka Sukh in Village Lutsaan was traced to two villagers, the tailor, Birendra Singh Khushwaha, and the postmaster, Bapu. Although they are a generation apart in age, and belong to different castes, they have much in common. Both are in occupations that bring them in contact with many villagers on a daily basis. Both are sparkplugs for social change in Lutsaan.

The tailor is a hyperactive fan of AIR, listening for 8 to 10 hours a day, and writing to AIR an average of five letters per day! He keeps a stack of postcards at hand in his tailor shop so he can jot down a comment to a radio program on the spur of the moment. He has 20 different name stamps that he uses to address the letters to his favorite AIR program or to sign his name on the postcards (he stamped the 1996 poster-letter about dowry with three different stamps). He says that he has written 12,000 postcards and letters to AIR since the early 1990s. In the poster-letter, he told how he became a fan of AIR (explained at the opening of this chapter). The tailor had personally experienced certain of the educational issues discussed in the radio soap opera and related to the characters, especially Ramlal who changes his stripes from being a vicious village bully to become a development change agent. The tailor’s shop is located centrally in the village, and its door is always open, with the radio on. Several people are usually in the tailor shop, gossiping, listening to AIR, and discussing the program. The traffic through the tailor’s shop provided a convenient way for the tailor to obtain signatures and thumbprints on the poster-letter.

Om Prakash Sharma (Bapu), the 55-year-old postmaster of Lutsaan, has a home-cum-office. The post office is located in one room of his home. He is a Brahmin, one of the few high-caste individuals in Village Lutsaan, which is dominated by the Jat farmer caste. He has the only telephone in the village, which he allows others to use. Bapu is known for his altruism. He has a small buffalo corral in the courtyard of his home and this is where villagers bring their sick buffalo for treatment. Bapu barters the cost of the drugs in exchange for milk. Like the tailor, Bapu was a devoted fan of Tinka Tinka Sukh, often delaying his evening meal in order to listen. He says that: “Six months later, we still talk about Tinka Tinka Sukh.” Often, Bapu listened to the radio soap opera and then discussed the episode with his friends. He knows the names of each character and can describe what they are like. Bapu’s son, Prem Shankar, aged 30, was married one month before our visit to Lutsaan. Bapu would not accept dowry from the bride’s parents. Prem volunteers his time as secretary at the all-women dairy cooperative in Lutsaan, maintaining their financial ledgers. He told us that his inspiration is Suraj, a positive role model in Tinka Tinka Sukh, who volunteers his time for community development activities.

One week before our visit to Lutsaan, a 14-year-old girl was married, suggesting that Tinka Tinka Sukh was not completely effective in changing the village norms. This child marriage meant that she had to drop out of school. Her father, a low-caste community member, told us that he knew that child marriage and paying dowry were illegal in India, but he did not expect the police to interfere. Bapu, the postmaster, although visibly angered by this recent marriage, shrugged it off as being a problem with the lower caste. This child marriage in Lutsaan suggests that an entertainment-education program can only do so much.

Why was Tinka Tinka Sukh so effective in stimulating social changes in Lutsaan? Exposure to the radio soap opera was higher in Lutsaan than elsewhere in North India. Prior conditions in the village helped magnify the effects of this entertainment-education radio program: a hyperactive radio listener (the tailor), a highly respected village leader in the postmaster, group-listening to the radio episodes, and the activities of a village self-help group.

Our experience in Village Lutsaan, during hot summer days in India in 1997, enriched our understanding of the potential and the limitations of entertainment-education.1

Entertainment’s Unrealized Educational Potential

This chapter investigates the basic tenets of the entertainment-education communication strategy, including its historical roots and recent applications in the United States and in developing countries. Entertainment, whether via a nation’s airwaves, popular magazines, or newspapers, is the most pervasive mass media genre; it tells us how to dress, speak, think, and behave (Browne, 1983; Piotrow, 1990). Thus, we are “educated” by the entertainment media, even if unintended by the source and unnoticed by the audience (Barnouw & Kirkland, 1989; Bineham, 1988; Chaffee, 1988; Cooper-Chen, 1994; Fischer & Melnik, 1979; Piotrow, Kincaid, Rimon, & Rinehart, 1997; Postman, 1985; Rogers, Aikat, Chang, Poppe, & Sopory, 1989; Rogers & Singhal, 1989, 1990; Singhal & Brown, 1996; Vink, 1988; Wang & Singhal, 19...