![]()

Part One

General Concepts

![]()

1 The Green Bottom Line

Martin Bennett and Peter James

THIS CHAPTER begins by addressing three questions:

- What is environment-related management accounting?

- Why should it be undertaken?

- Who should do it?

It then identifies relevant sources of financial and non-financial information and discusses the ways in which existing management accounting techniques can be modified to take account of environmental issues. A final section draws conclusions and is followed by an appendix on definitions of environmental costs and benefits.

What is Environment-Related Management Accounting?

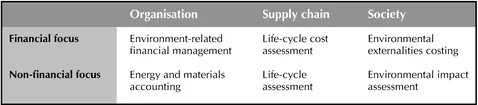

The term ‘environmental accounting’ has been used to cover both national and firm-level accounting activities, the processing of both financial and non-financial information, and the calculation and use of 7monetised external damage costs as well as those that are internal to the firm (see Chapter 2). For clarity, Figure 1 distinguishes six different domains of environmental accounting that are relevant to the firm level, based on their boundaries of attention—an individual organisation, the supply chain of which it forms part and the whole of society—and the extent to which they focus on financial and/or non-financial information. The six domains that emerge can be defined in this way (the two life-cycle definitions are based on the US Environmental Protection Agency discussion in Chapter 2):

Figure 1: Domains of Firm-Level Environmental Accounting

- Energy and materials accounting: the tracking and analysis of all flows of energy and substances into, through and out of an organisation

- Environment-related financial management: the generation, analysis and use of monetised information in order to improve corporate environmental and economic performance

- Life-cycle assessment: a holistic approach to identifying the environmental consequences of a product or service through its entire life-cycle and identifying opportunities for achieving environmental improvements

- Life-cycle cost assessment: a systematic process for evaluating the life-cycle costs of a product or service by identifying environmental consequences and assigning measures of monetary value to those consequences

- Environmental impact assessment: a systematic process for identifying all the environmental consequences of the activities of an organisation, site or project

- Environmental externalities costing: the generation, analysis and use of mon-etised estimates of environmental damage (and benefits) created by the activities of an organisation, site or project

Firm-level environmental accounting can potentially encompass all of the six domains but, in practice, is centred in the first two as the areas where accountants’ experience and accounting techniques (as opposed to those of, say, environmental managers and environmental management techniques) have the most to contribute.

The literature on firm-level environmental accounting initially focused—and, to a considerable extent, still does—on external accountability to stakeholders outside the company, rather than on serving the needs of management. There are two distinct aspects to this:

- A broad concept of accountability to all of a company’s stakeholders

- The traditional financial accounting focus of providing accurate and reliable information on the financial position of companies to their shareholders

In both cases, the emphasis is on collecting, verifying and reporting information to audiences outside the organisation, as opposed to the internal audience of the organisation’s own management.

The broad accountability approach is founded on the premise that the responsibility of companies should not be seen—as in the traditional micro-economic theory that still largely shapes company law—as limited to maximising profits or value for the benefit of their owners (shareholders) alone. On the contrary, the activities of companies have wider impacts on society and the environment, and an enlightened company will recognise this and ensure that it maintains good relationships with all its stakeholder groups in order to preserve its implicit ‘licence to operate’ (RSA 1994). This was the main theme in much of the early literature on environmental accounting (Bebbington and Thompson 1996; CICA 1992; Grayson, Woolston and Tanega 1993; Müller et al. 1994; Gray, Bebbington and Walters 1993; Gray, Owen and Adams 1996; Owen 1992; Zadek, Pruzan and Evans 1997) and has been largely responsible for prompting many companies to publish corporate environmental reports (KPMG 1997; Lober et al. 1997; Owen, Gray and Adams 1997; SustainAbility/UNEP 1997). Even some authors who have seen themselves as following a management accounting approach—i.e. one that focuses on provision of information for internal decision-making—have, in practice, placed considerable emphasis on its role in generating information for external stakeholders (Birkin and Woodward 1997a–f).

There has also been a narrower concern, particularly within the accountancy profession and among financial regulators such as the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), that regular financial reports by companies to their shareholders may be significantly inaccurate. It is said that these do not adequately reflect the effect on the business of environmental issues, particularly in the US where ‘Superfund’ liabilities can be substantial (Ethridge and Rogers 1997; Schoemaker and Schoemaker 1995). The accounting profession in Europe and internationally has also considered this and has provided guidance to its members (ASB 1997; FEE 1996; IASC 1997; ICAEW 1996), although the prevailing consensus seems to be that existing financial accounting practices, so long as they are properly applied, are adequate to deal with environmental effects on business and do not require change.

Both these bodies of work can be seen as adopting a ‘financial accounting’ approach, i.e. with a focus on reporting to external stakeholders. However, there is now a growing literature that adopts a genuine ‘management accounting’ approach that does focus on providing information to support internal decision-making (although, of course, much of this data may be of value to external stakeholders also). The starting point for this was probably the well-known ‘3P’ (Pollution Prevention Pays) initiative introduced by 3M during the 1970s. This was expanded during the 1980s and early 1990s by further pollution prevention initiatives introduced by companies and/or government-sponsored programmes in the Netherlands, USA and other countries. These required more precise data on the costs and benefits of environmental action and therefore spawned new methodologies such as the ‘total cost assessment’ technique developed by the Tellus Institute for the US Environmental Protection Agency (White, Becker and Goldstein 1991; see also Chapter 14). The EPA has since sponsored a number of studies and publications on the topic—many of which are summarised in this volume—and the Tellus Institute has continued with its applied research and application. Other important US contributions have been made by Bailey and Soyka (1996), Ditz, Ranganathan and Banks (1995), Epstein (1996b, 1996c), IMA (1995) and Rubenstein (1994). In Europe, the topic has been addressed by, inter alia, IIIEE and VTT (1997), Schaltegger, Müller and Hindrichsen (1996), Tuppen (1996) and Wolters and Bouman (1995).

This book is positioned within this management accounting approach and contains contributions from most of the authors and organisations cited. We see this focus as being complementary—rather than an alternative—to a financial accounting approach. It addresses different needs and is also necessary in order to provide many of the data that are of interest to external stakeholders.

Our working definition of environment-related management accounting is therefore:

The generation, analysis and use of financial and non-financial information in order to optimise corporate environmental and economic performance and achieve sustainable business.

The term ‘environmental’ precedes ‘economic’ in order to indicate an environmental bias. As we discuss below, the main aim at present must be to overcome the barriers to environmental action that can be created by current management accounting practices. However, there will be occasions when even modified practices reveal tradeoffs between environmental and economic parameters which will result in the latter being given priority over the former. For this reason, we use the term ‘environment-related management accounting’ in our following discussions to signal that the activity is focused on meeting corporate as well as societal objectives.1

We include the term ‘sustainable business’ to indicate that, although much of the practical action generated by environment-related management accounting involves adaptation of existing activities, such as management accounting and environmental management, part of its objective is to support the goals of sustainable development (see below).

A final point is that environment-related management accounting relies heavily on non-financial information, particularly regarding inputs, outputs and flows of energy, materials and water (see below). Some would see the development of this information as a primary objective (for example, Birkin and Woodward, 1997a–f). However, we would argue that, at present, such information is a means rather than an end for environment-related management accounting. Its ultimate objective is to provide information to support environment-related decision-making by mainstream business managers. While this may sometimes require ‘raw’ physical data, we believe that the need is more often for either productivity measures (e.g. materials consumption or waste generation per unit of production) or information expressed in financial units. This is because:

- For profit-seeking firms, the ultimate objective (maximising shareholder value, or profitability) is expressible in monetary form, and information that can be expressed in the same or related (e.g. productivity) terms is always likely to attract more immediate attention.

- The financial side of management is relevant to all functions, including environmental management. Not only do environmental budgets need to be managed, but proposals for action that can be justified in terms of conventional methods of financial investment appraisal and product costing, for example, are more likely to be successful.

A supporting point is that environmental and operational managers are fully capable of developing and using such data and are often doing so in practice. Hence, there is no need to invent a new discipline or activity to accomplish this. Indeed, to do so could be counter-productive because it may foster resentment and defensiveness among line staff about territorial aggrandisement by accountants.

More pragmatically, there is little evidence that the accountancy and finance functions are greatly involved in energy and materials accounting activities in most companies or have the interest and expertise to do so in the near future. The Zeneca case study in Chapter 19, for example, found that the substantial savings that followed such an exercise at the company’s Huddersfield site were almost entirely driven by operational staff and had only a marginal accounting involvement.

At first sight, this argument may appear to be in conflict with advocates such as Kaplan and Norton (1992, 1993, 1996a, 1996b), Simmonds (1991) and Wilson (1997), who have argued for the development of strategic management accounting and, as part of this, greater use of non-financial data and indicators. However, we would argue that their views are less relevant to an area that usually has a relative abundance of non-financial data and a shortage of financial data. Moreover, their arguments have had—at least as yet—only limited impact on management accounting practice. While there is certainly more attention being paid to the strategic use of non-financial data and indicators through ‘balanced scorecards’, anecdotal evidence suggests that it is more often strategic planning, business excellence and other functions that are implementing it, rather than accountancy and finance. Research in other areas of management accounting has also found that practice can be slow to adapt (Drury et al. 1993) and that initiatives in new or developing areas such as non-financial performance measurement are often taken by functions other than accounting.

For all of these reasons, we would suggest that the immediate priorities for environment-related management accounting are the generation, analysis and use of financial or neo-financial (e.g. indicators of resource productivity) information, and modifying and adapting the established techniques of management accounting and financial management to take account of environmental issues.

Why Undertake Environment-Related Management Accounting?

The primary aim of environment-related management accounting is to better inform and otherwise support decision-making processes that are influenced by environmental factors—which are primarily those of accounting and financial management, environmental management and operational management.2 Some of the specific objectives that this creates can be summarised as:

- Demonstrating the impact on the income statement (profit and loss account) and/or balance sheet of environment-related activities

- Identifying cost reduction and other improvement opportunities

- Prioritising environmental actions

- Guiding product pricing, mix and development decisions

- Enhancing customer value

- Future-proofing investment and other decisions with long-term consequences

- Supporting sustainable business

Income Statement and Balance Sheet Impact. As many of the chapters in this book show, there is growing evidence that environment can have significant impacts on expenses, revenues, assets and liabilities and that these impacts are often underestimated. Making such financial impacts apparent can make it easier to take, and win support for, further environmental initiatives.

In the US, most attention has focused on the balance sheet issue of environment-related liabilities. This is a consequence of the high levels of damage claims and fines, and of specific legislation such as that requiring the clean-up of contaminated land. It has been estimated that American industry may be under-provided for ‘Superfund’-related clean-up liabilities by up to a trillion dollars (Schoemaker and Schoemaker 1995). Liabilities are less in the UK and other European countries, but still significant for some companies. They may become more significant if proposed legislation o...