![]()

CHAPTER

1

Introduction and Overview

Jane D. Brown

University of North Carolina-Chapell Hill

Jeanne R. Steele

University of St. Thomas

Kim Walsh-Childers

University of Florida

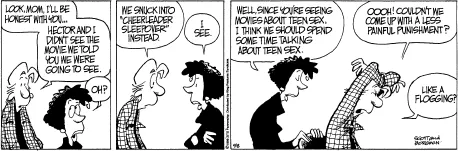

ZITS

Reprinted with special permission King Features Syndicate

The idea of adolescence is a relatively recent phenomenon and to some extent peculiarly American. In some cultures this transitional stage between childhood and adulthood is brief—a child’s physical “coming of age” is acknowledged as readiness to assume the adult roles of reproduction, parenting, and work. But in the United States, adolescence has become a relatively long life stage—generally marked at the beginning by both biological changes (a growth spurt and development of secondary sexual characteristics, e.g., breast, penis, and pubic hair growth) and by social factors (increasing independence from parents and increasing influence of peers). As one commentator put it: “America invented a space between the child’s ties to family and the adult’s re-creation of family. Within this space, America’s teenagers are supposed to innovate, to improvise, to rebel, to turn around three times before they harden into adults” (Rodriguez, 1999, p. 91).

WHAT IS ADOLESCENCE?

Developmental psychologists typically divide the life stage of adolescence into three overlapping periods: early (8 to 13 years old for girls, 11 to 15 for boys), middle (13 to 16 for girls, 14 to 17 for boys), and late (16 and older for girls and 17 and older for boys (Haffner, 1995). The stages are marked by physical, cognitive, social, and psychological development. An early adolescent, just beginning to adjust to the physical changes of puberty, may be especially concerned about his or her body image and will begin to concentrate on relationships with peers. The average age of first menarche has been dropping, so that today the average age for girls is 12½ years old; in 1900, the average age was 15 (Herman-Giddens et al., 1997). Some marketers have divided this early stage even further, focusing on what they call “tweens”—youth who are between childhood and adolescence, typically 8-to 11-year-olds who are beginning biological development and may be enticed by the allures of adolescence (Kantrowitz & Wingert, 1999).

Middle adolescents typically are attaining increased independence from their families, paying more attention to their peers, and experimenting with relationships and sexual behaviors. Late adolescents, in general, are becoming more secure about their bodies, gender roles, and sexual orientation and have developed greater intimacy skills as they begin to define and make the transition to adulthood.

Not all adolescents, however, mature at the same rate. Some 15-year-olds may be ready to assert themselves in sexual relationships but others may still be disgusted by kissing scenes in TV shows (Brown, White, & Nikopoulou, 1993). “Adulthood,” as traditionally understood, may not be entered until well into the 20s as educations are pursued and the establishment of new families and partnerships is postponed. The median age for first marriage in the United States today is older than it ever has been; in 1996, more than half the men who were getting married for the first time were 27 years old or older and half the women were 25 years old or older (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1997). So, in the United States, young people may spend 9 to 17 years being considered adolescents.

SEXUAL TEENS

And therein lies one of the current paradoxes of teen sexuality. Is it fair or reasonable to expect adolescents to wait so long between sexual maturity and sexual activity? Adherents of what some would call the “old morality,” based primarily on Christian religious asceticism, would say yes, sexual activity should be reserved for heterosexual marriage. In contrast, advocates of what might be called the “new morality” argue no, sexual pleasure is an important part of human behavior and should not be repressed or forced into a narrow set of restrictive norms (Hyde, 1994). Others take more of a middle ground.

In some European countries, the Netherlands, France, and Germany, for example, where adolescence is not considered such a specific life stage as it is in the United States, the prevailing understanding is that sexuality is a normal part of human development. Rather than asking youth to abstain from intercourse until marriage, health advocates promote values of respect and responsibility and encourage communication in relationships. Sex education is integrated throughout many school subjects and grade levels, and young people have access to both birth control pills and condoms if they have sexual intercourse. Does this openness result in early sexual intercourse and promiscuity? No; on the contrary, youth in these European countries begin having sexual relations more than one year later than American teens and have fewer sexual partners during their teen years (Kelly & McGee, 1999).

Unfortunately, in the United States today, cultural norms of appropriate adolescent sexual behavior are not easy to figure out. From some adult quarters teens will hear that you should be abstinent until married because otherwise you will have sinned. From others they will hear that it would be best if you wait until you are mature, but if you choose not to, use protection so you won’t get pregnant, a disease, or even die.

Girls may learn on the street and in the school yard that if they express their sexual desires they will be “bad girls.” If they choose to be “good girls” instead, they will sense it isn’t as much fun and may find themselves vulnerable to aggressive boys who don’t believe that “no” means “no” (Tolman & Higgins, 1996).

Boys are subject to a more consistent message, which is basically that the more women a man has sex with, the more of a man he is because a “real” man would never say no to the opportunity to have sex with a woman. This expectation is problematic for those boys who do not aspire to stud status.

To most teens, sexuality is not just about having intercourse, it’s also about attractiveness, reputation, relationships, and finding love and intimacy. The dominant adult discourse, however, tends to focus on sexual intercourse, too often leaving out the other concerns many teens find equally, if not more, important. We saw this in sharp relief when U.S. Surgeon General Jocelyn Elders was forced to resign because she had dared discuss the possible benefits of masturbation. While the adults battle, teens are provided an inadequate, often confusing, and potentially harmful picture of sexual expectations.

Fortunately, an emerging body of research has begun to examine some of the other aspects of teens’ sexuality and may help stimulate a healthier dialogue about teen sexuality. As a whole, these studies show that most young people live through adolescence in good physical and mental health, coming into adulthood capable of living fulfilling sexual lives. Most teens who have intercourse do so responsibly (Haffner, 1995). Some adolescents, however, have a tougher time sorting out who they are and how they want to be sexually, and some are at significant risk for negative outcomes—surrounded by a culture that at best provides mixed messages, and at worst promotes unhealthy sexual attitudes and behaviors.

Here’s a brief profile of American adolescents’ sexual activity, defined broadly to include the precursors to as well as outcomes of sexual intercourse.

Sexual Attractiveness

Getting comfortable in a changing body is a daily concern of most teenagers. Girls and boys can spend hours in front of the mirror getting their hair, makeup, and clothes “just right.” A large survey of adolescents in Minnesota found that one out of three girls and one out of nine boys said they were “highly concerned” about their physical appearance (Blum, 1997). In a national survey, half of the adolescent girls said they had been on a diet; three fourths of these said because they wanted to look better (Commonwealth Fund, 1999). But “looking good” can become a dangerous preoccupation. Girls not yet finished growing are having cosmetic surgery to reshape their noses and eyelids, and to reduce or enlarge the size of their breasts (Kalb, 1999).

For some girls, getting thin enough becomes an obsession; dangerous eating patterns such as self-starvation and binging and purging are not uncommon, especially among White middle-class girls. In one national survey, 13% of early adolescent girls and 18% of middle and late adolescent girls reported having binged and purged (Commonwealth Fund, 1999). Anorexia nervosa affects 1% of girls ages 16 to 18, and bulimia affects 15%. These are serious illnesses that can result in damage to the body’s organ systems and even death (Palla & Litt, 1988).

Dating, Kissing, and Sexual Touching

A majority of American teenagers date; 85% say they have had a boyfriend or girlfriend and have kissed someone romantically. By the age of 14, more than half of all boys have touched a girl’s breasts, and a quarter have touched a girl’s vulva. One fourth to one half of young people report experience with fellatio and cunnilingus (Newcomer & Udry, 1985; Roper Starch Worldwide, 1994).

Sexual Orientation

Males’ and females’ sexual orientation often emerges during adolescence. Two to five percent of teenagers report some type of same-gender sexual experience (Coles & Stokes, 1985). In one study of middle and late adolescents, 88% described themselves as predominantly heterosexual, 1% as bisexual or predominantly homosexual, and 11% were “unsure” of their sexual orientation. Older adolescents were more likely than the younger to be sure (Remafedi, Farrow, & Deisher, 1991). Gay males report developing a gay identity between the ages of 15 and 17, whereas lesbians report knowing their sexual orientation between the ages of 18 and 20 (Downey, 1994).

Homosexual feelings can be difficult for teens in a culture that continues to stigmatize and ostracize nonheterosexuals. Recent studies have found that lesbian, gay, and transgender youth are 2 to 6 times more likely to attempt suicide than other youth; and they may account for 30% of all completed suicides among teens, although they are only 10% or less of the teen population (Gibson, 1989; Savin-Williams, 1994).

First Sexual Intercourse

More than 80% of Americans first have sexual intercourse as teenagers, although the majority wait until middle and late adolescence. The average age of first intercourse is 16 for males and 17 for f...