This is a test

- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Integrating Individual And Family Therapy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Presents a comprehensive model of integrating individual and family therapy with clinical examples to illustrate the model. Throughout the book, the importance of tailoring the structure and process of therapy to meet the particular needs of specific individuals and families is emphasized.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Integrating Individual And Family Therapy by Larry B. Feldman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Salute mentale in psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

_____________

_____________

_____________

Integrative Multilevel Conceptualization of Clinical Problems

CLINICAL PROBLEMS have generally been conceptualized by individual psychotherapists in terms of intrapsychic processes (e.g., Beck, 1976; Berman, 1979; Kendall & Bra-swell, 1985;, Luborsky, 1984) and by family therapists in terms of interpersonal processes (e.g., Aponte & VanDeusen, 1981; Gordon & Davidson, 1981; Minuchin, 1974; Stanton, 1981). From an integrative, multilevel perspective, clinical problems are the result of both intrapsychic and interpersonal processes, along with the synergistic interactions between them. Ignoring or minimizing either level leads to an incomplete understanding of individual and family dysfunction.

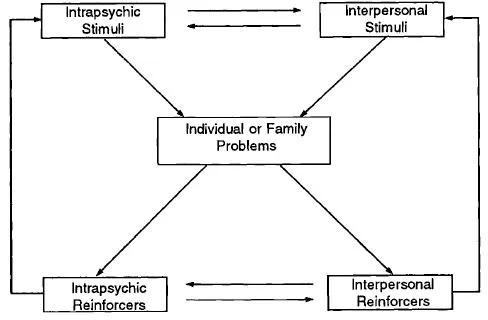

The Integrative Multilevel Model (see Figure 1.1) combines and integrates the intrapsychic and interpersonal perspectives. The intrapsychic components of the model are derived from psychoanalytic and cognitive theory. The interpersonal components are derived from behavioral and family systems theory. In the following sections, the specific concepts from each of these theoretical frameworks will be described. Subsequently, the integrative model will be presented and illustrated with clinical examples.

Figure 1.1

Integrative Multilevel Model

Integrative Multilevel Model

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Psychoanalytic Framework

From a psychoanalytic perspective, clinical problems are defensive reactions to unconscious anxiety (signal anxiety), defined as fear of unknown (i.e., unconscious) danger situations (S. Freud, 1926). In childhood, the major danger situations are interpersonal ones—disapproval, abandonment, or attack by significant others. Conscious and unconscious fantasies about these danger situations are present to some degree in all children, but they are especially strong when one or both parents have been unem-pathic, unavailable, neglectful, or abusive. Under these circumstances, a healthy sense of self-cohesion and self-esteem does not develop (Kohut, 1971, 1977). Instead, the self is experienced (consciously or unconsciously) as weak, helpless, worthless, or evil and thus vulnerable to rejection or attack by significant others.

As external relationships are internalized, anxiety is increasingly associated with internal representations of significant others and of the self in relation to these internalized others. Anxiety-generating fantasies are then projected into new relationships, such as those with teachers and peers. In adulthood, these fantasies are unconsciously transferred to current relationships, especially marital and family relationships.

In marital and family systems, anxiety generally takes one of two forms: fear of interpersonal closeness or fear of interpersonal distance. Fear of interpersonal closeness (intimacy anxiety) is manifested as a preconscious danger signal in response to actual or anticipated interpersonal closeness. In distressed families, this type of fear leads to dysfunctional distancing in marital and/or parent-child relationships. The nature and effects of intimacy anxiety are illustrated by the following examples.

Clinical Illustrations

(1) Each spouse in a conflictual marriage avoids initiating positive, intimacy-promoting interactions. This avoidance behavior is stimulated by each spouse’s unconscious fear of interpersonal closeness. The husband fears that if he gets too close to his wife, he will be attacked by her. The wife fears that if she gets too close to her husband, she will be abandoned by him. Both spouses’ fears are based, in part, on projection of unconscious introjects derived from experiences in their families of origin, where the husband was frequently denigrated by his mother and the wife was frequently ignored by her father.

(2) The father of a depressed boy spends little time with his son because he is unconsciously afraid that if he tries to have a close relationship with him, his wife will resent his “intrusion” into the extremely close relationship she has with the boy. This anxiety is derived, in part, from the father’s experiences in his family of origin, where his mother was very possessive of him and often actively excluded his father from their relationship.

Fear of interpersonal distance (separation anxiety) is manifested as a preconscious danger signal in response to actual or anticipated interpersonal distance. In distressed families, this type of fear leads to inhibition of healthy autonomy in marital and/or parent-child relationships. The nature and effects of separation anxiety are illustrated by the following examples.

Clinical Illustrations

(1) An agoraphobic woman is afraid to leave her house without being accompanied by her husband. Her fear is derived, in part, from experiences in her family of origin, where she was overprotected by her mother, who constantly warned her of the dangers of going out of the house alone and who reinforced her anxious, dependent behavior with excessive attention and concern.

(2) A school-phobic boy is afraid that if he goes to school something terrible might happen to his mother. This fear is based, in part, on projection of his unconscious hostility toward his mother, whom he experiences as withdrawn and unavailable. His symptom is a reaction to the anxiety generated by his unconscious hostility.

In order to prevent conscious experiencing of intense anxiety, defense mechanisms are created to block awareness of unconsciously perceived danger situations and of the thoughts and impulses (sexual, aggressive, or narcissistic) that are associated with these danger situations (A. Freud, 1933; S. Freud, 1926; Kohut, 1971). Defense mechanisms are thus a form of intrapsychic avoidance behavior.

By blocking conscious experiencing of anxiety, this avoidance behavior prevents emotional desensitization. It also prevents cognitive reappraisal of the unconsciously perceived danger situations that trigger the anxiety. As a result, there is a perpetuation of the anxiety, the defenses against the anxiety, and the unconscious perception of interpersonal danger (P. L. Wachtel, 1985). The following examples illustrate the role of defenses against anxiety in the generation of individual symptoms and dysfunctional family interactions.

Clinical Illustrations

(1) A 15-year-old boy is in danger of being expelled from high school because he is failing most of his courses and he chronically disobeys the school rules. Clinical assessment reveals that his antisocial behavior is a defense against unconscious anxiety. Based on the difficulties he had with school work in elementary and junior high school, he is now afraid that he will be rejected by his high school peers because they will perceive him as stupid. In order to avoid this, he rejects school and seeks acceptance and admiration as an antisocial rebel. His anxiety is also derived from the frustration and rage that he feels about his inability to learn. His symptoms are, in part, a way of acting out these feelings and, in part, a plea for help in learning to control them.

(2) A conflictual couple are unable to sustain periods of positive relating. After one or two days of such relating, they begin arguing in increasingly destructive ways. Clinical assessment reveals that during the periods of positive relating, each spouse begins to unconsciously expect the other to say or do something hurtful. These unconscious expectations generate increasingly intense anxiety signals. To defend against this anxiety, both spouses become hy-pervigilant to anything in the other’s behavior that could be construed as neglectful or critical. When one of them perceives such behavior, he or she responds with verbal attacks on the other. These aggressive behaviors temporarily reduce their anxieties. At the same time, the others aggressive behaviors are unconsciously interpreted as confirmatory evidence of each spouse’s own initial negative expectations, thus reinforcing the vicious circle that repeatedly generates destructive arguing.

Cognitive Framework

Cognitive theorists (e.g., Beck, 1976; Ellis, 1973; Meichenbaum, 1977) view clinical problems as primarily resulting from dysfunctional cognitions—that is, irrational or distorted perceptions, thoughts, expectations, and beliefs. Dysfunctional cognitions generally operate outside of conscious awareness but are capable of entering awareness with directed attention.

Perceptual distortions are inaccurate or incomplete perceptions of others, self, or the relationship between self and others. Such perceptions are partially accurate, but they are distorted by the mechanisms of magnification and minimization. Magnification is the process of perceiving the frequency, intensity, or importance of particular behaviors, thoughts, or feelings as greater than it actually is. Minimization is the opposite of magnification—that is, the frequency, intensity, or importance of particular behaviors, thoughts, or feelings is perceived as less than it actually is. Usually these two forms of perceptual distortion operate together.

Clinical Illustrations

(1) The mother of a school-phobic girl magnifies her daughter’s expressed anxiety and minimizes her coping capacities. As a result, she perceives her as terrified, helpless, and fragile when, in reality, she is frightened but capable of effective coping.

(2) The husband and wife in a conflictual marriage each perceive him-or herself as the “innocent victim” of an inconsiderate, selfish spouse. While these perceptions are not totally false, they are distorted by magnification of the other’s negative behavior and of each one’s own positive behavior and by minimization of the other’s positive behavior and of each one’s own negative behavior.

Dysfunctional thoughts (“automatic thoughts”; “dysfunctional self-statements”) are thoughts about self or others that distort reality by means of overgeneralization (drawing a generalized conclusion from a specific, limited experience), arbitrary inference (inferring a specific conclusion on the basis of minimal evidence), or catastrophic projection (assuming that noncatastrophic events will have catastrophic consequences). Examples of dysfunctional automatic thoughts are (1) A depressed adolescent boy responds to any setback or failure with the automatic thought, “I’m never successful at anything”; (2) An agoraphobic woman begins to feel anxious and thinks, “I’m going to die”; (3) The husband of an agoraphobic woman reacts to any sign of anxiety in his wife with the thought, “She needs my help”; and (4) The wife in a distressed marriage reacts to any form of inconsiderate behavior by her husband with the thought, “This is absolutely intolerable.”

Perceptual distortions and dysfunctional self-statements are derived, in part, from unrealistic expectations. These are rigid, arbitrary, or irrational expectations of self, others, or relationships. Examples of unrealistic expectations are “I should always get perfect grades in school”; “My wife should know what my feelings are without my having to tell her”; “Our family should never have any disagreements.”

Unrealistic expectations are based on irrational beliefs —that is, implicit assumptions about self, others, or relationships that are derived from irrational premises. Examples of such beliefs are “If I am not perfect, I am worthless”; “If you really love someone, you can tell what he or she is feeling just by looking at him or her”; “A happy family doesn’t have disagreements.”

Behavioral Framework

From a behavioral perspective, individual and family interactional problems are primarily the result of interpersonal problem stimulation and problem reinforcement processes (Goldfried & Davison, 1976; Gordon & Davidson, 1981; N. S. Jacobson, 1981). Interpersonal problem stimuli are behaviors by one or more individuals that lead to the arousal of dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, and behaviors in one or more other individuals. Interpersonal problem reinforcers are behavioral reactions by one or more individuals to dysfunctional behavior by one or more other individuals that have the effect of increasing the probability of recurrence of the dysfunctional behavior.

Interpersonal problem stimulation is often derived from a low level of positive responsiveness by one or more individuals to constructive behavior by one or more other individuals. The lack of positive responsiveness is frustrating and, over time, demoralizing. These emotional reactions then lead to dysfunctional behavior.

Clinical Illustrations

(1) The parents of an underachieving boy do not praise him for his positive accomplishments because they want him to “work to his potential. ” The lack of reinforcement discourages him from trying to improve his performance.

(2) Each spouse in a conflictual marriage ignores the positive, intimacy-promoting behaviors of the other because each one is “sure it won’t last.” As a result, the frequency of positive behavior diminishes and the frequency of negative, hostile behavior increases.

Interpersonal problem stimulation also occurs when individuals are not clear, congruent, or consistent in their communications with each other.

Clinical Illustrations

(1) The parents of a 9-year-old boy with behavior control problems are inconsistent in their communication of expectations. One day they tell him that he is not allowed to watch television for more than an hour; the next day they allow him to watch television for three hours. The lack of consistency in the parents’ expectations contributes to the lack of consistency in their son’s behavior.

(2) The spouses in a conflictual marriage do not discuss their expectations of each other because each one believes that the other should “know” what he or she wants without having to spell it out. As a result, each spouse frequently behaves in ways that the other experiences as thoughtless and hurtful.

A third major source of interpersonal problem stimulation is aversive behavior by one or more individuals toward one or more other individuals. The most extreme form of aversive stimulation is physical or sexual abuse. In recent years, it has become clear that these forms of trauma occur much more often than was formerly believed and are associated with a wide variety of individual and interactional problems (Finkelhor, 1984; Kempe & Kempe, 1978). In addition to physical or sexual abuse, verbal abuse is a common interpersonal problem stimulus. Verbal abuse may take the form of yelling, sarcasm, generalized criticisms, put-downs, or name-calling. These behaviors stimulate feelings of hurt and anger and lead to escalating spirals of dysfunctional interaction.

More subtle, but equally significant, forms of aversive stimulation are overintrusiveness and overprotectiveness. These behaviors inhibit the development of autonomy and self-esteem and stimulate excessive dependency and separation anxiety (Williams, Berman, & Rose, 1987).

Aversive stimulation may result from direct interaction between two or more individuals or it may be the result of one individual observing aversive interactions between two or more other individuals. For example, children in dysfunctional families are indirectly affected by observing the dysfunctional interactions of their parents.

Interpersonal problem reinforcement occurs when one or more individuals react to dysfunctional behavior by one or more other individuals in such a way that the probability of the dysfunctional behavior rec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Brunner/Mazel Integrative Psychotherapy Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Integrative Multilevel Conceptualization of Clinical Problems

- 2. Integrating Individual and Family Assessment

- 3. Integrative Multilevel Treatment Planning

- 4. Integrative Multilevel Model of Therapeutic Change

- 5. Integrating Individual and Family Therapy Techniques

- 6. Potential Problems and How to Deal With Them

- 7. Phases of Individual and Family Therapy Integration

- 8. Conclusion

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index