![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Need for Effective Pricing

AS WATER SCARCITY INCREASES, water quality deteriorates, water-related environmental and social concerns rise, and climatic change amplifies extreme events, such as floods and droughts, the water sector becomes a critical policy challenge in many countries. Although professionals widely agree on what constitutes sound water resources management, debate continues about the best ways of implementing policies in this sector. Policymakers have considered pricing water— an ever-debated policy intervention—in many variations. Setting the price “right,” some say, may guide different types of consumers in utilizing water efficiently by sending a signal about the value of the scarce resource. Aside from efficiency, itself an important policy objective, the pricing of water has to consider equity, accessibility, and the implementation cost associated with the right pricing.

Irrigated agriculture in developing countries consumes between 75% and 90% of all water used and contributes about 38% of the world's food (World Bank 2001). It has played a major role in generating employment in rural areas and providing food to the urban population at relatively low prices. Globally, the irrigated agriculture area increased annually by about 2.4% in the 1970s and by 14% in the 1980s and late 1990s. Further yearly increases of 0.4% are projected for the next 34 years (base year 1995/96, FAO 2000). Thus, the irrigation sector, which already uses a large share of global water, will continue to increase its demand for irrigation water in the years to come.

We may have exceeded our water supply management capabilities, for expanding the water supply by means of dams, diversion projects, or extractions from aquifers. Yet demand management policies such as pricing strategies are still under-utilized in many parts of the world.

A growing trend in the irrigation sector around the world stresses pricing and charging for water as a primary means of regulation. For example, the European Union's Water Framework Directive of 2000 calls for full cost recovery in all sectors to reflect the true expense of using water (Kallis and Butler 2001). In developing countries, in many cases, the conditions for disbursing loans for an irrigation project by international development agencies require that “appropriate” pricing of the irrigation water be introduced. What exactly these “appropriate” and “true” water prices are and how they should be applied, however, is not clear. For example, should income-distribution criteria be considered? How should the existing water institutions affect the choice of pricing method and price levels? What are the implications of asymmetrical information between the water pricing agency and water users? What are the prospects for decentralized (i.e., market-based) pricing? What are the relationships between macroeconomic policies and water pricing and other agricultural policies? These are some of the questions water managers face when evaluating the feasibility of irrigation and water management projects throughout the world.

Disagreements among competing groups of water users are common, particularly if they are in different economic sectors. Surprisingly, however, economists also disagree about the best ways of addressing these issues. Disagreement stems partly from general confusion over basic economic principles but also from the high sensitivity of water pricing methods to each locality's physical, social, institutional, and political setting. Moreover, many countries lack the tradition and the experience of pricing water. Experience with water pricing was acquired through water pricing reforms in various countries (Dinar 2000). India's Andra Pradesh Water Consolidation project, Mexico's National Water Resources project, Pakistan's National Drainage Program project, and Morocco's Large Scale Irrigation Improvement project, among others, provide detailed information. This accumulated experience suggests that the entire issue of water pricing is much more complex than initially perceived.

This general confusion indicates that it would be useful to clarify the basic concept of water pricing and to establish guidelines on the factors to be considered in the pricing of irrigation water under different circumstances. The primary criterion used to measure the performance of a water-pricing method is efficiency, broadly defined to include implementation costs. Efficiency criteria are concerned with the overall benefit that can be generated from irrigation water but pay no attention to the way this benefit is distributed among water users. Because distributional considerations are important both on ethical grounds and in their ability to implement a pricing method, by affecting implementation costs, they are included here. In addition, the institutional setting, including property rights and water law, and the political setting are also significant when evaluating the merits of a water pricing method.1 In addition to giving water managers some directions for pricing irrigation water, such guidelines can be useful when conducting a cost–benefit analysis during the planning stage of an irrigation project, as these prices will determine the water revenues associated with the different pricing schemes.

The water pricing methods now in use differ in their implementation, the institutions they require, and the information on which they are based (Tsur and Dinar 1997; Dinar and Subramanian 1998). They also differ with regard to the efficiency and equity performance of their outcomes and implementation cost (Tsur and Dinar 1995, 1997). No single pricing method is superior in all possible circumstances. Each method has its pros and cons, depending on the situation under consideration. When selecting the method to be used it is thus important to identify the conditions that are appropriate for each pricing method. How these conditions affect the various pricing methods has to be understood to select and implement the appropriate method. Over time and across geographical regions, a variety of water pricing methods have evolved, including methods based on the volume of water used (i.e., volumetric), on output or other inputs, on the size of the irrigated or cultivated area (i.e., per-area charges), as well as on different forms of water markets (Dinar and Subramanian 1998). These methods differ in the way they are implemented, the institutions they require, and the information on which they are based. They also differ in the efficiency performance of their outcomes and cost of implementation (Tsur and Dinar 1997).

In this book we emphasize the importance of considering the links between economic activities at the microeconomic level and activities at the macroeconomic level.

Macroeconomic–Microeconomic Links

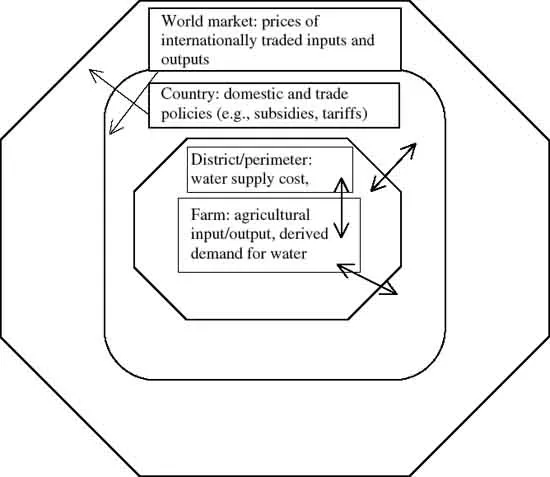

Figure 1.1 represents directions of effects between economic activities. The world market is shown at the top. A small country takes the world market as given and the arrow, representing direction of effects, projects one way. Otherwise, another arrow will extend from the country to the world market as well. There are feedback effects between all levels, and our analysis is aimed at unfolding them, particularly the ways economywide policies affect water allocation at the district and farm levels. These feedback effects are critically important as they create opportunities for policy change. Moreover, if these effects are not taken into account, the implementation of an apparent first-best policy such as a water market can result in a decrease in efficiency in economies where other policy distortions are present.

We discuss first the arrows that extend between the district or perimeter and farm levels and then show how economywide policies can influence these links.

District or Perimeter ↔ Farms

A water district or perimeter typically assumes the responsibility for supplying irrigation water to end users (i.e., farmers) in a confined region. Such an organization may be managed by the users as a water user association, by the regional or state governments, by a regulated public or private utility, or by any combination of these organizational structures. The organization exists to capture economies of scale and to regulate against various externalities associated with irrigation water supply.

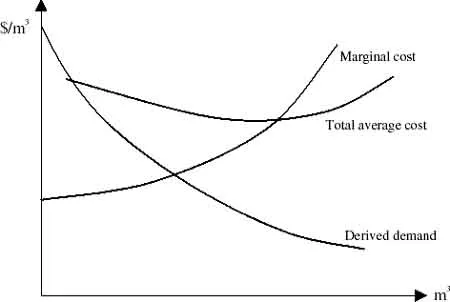

The district or perimeter delivers water to farmers according to prespecified rules and schedules and charges farmers for the irrigation water according to prespecified rates. To perform its functions, the organization must operate, maintain, and often construct water storage and conveyance facilities. The farmers demand water for use as an input in agricultural production. The district or perimeter then determines the cost of water supply, particularly the marginal and total average cost, while the farmers determine the derived demand for water (see Chapter 3) (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-1. Links Between Different Levels of Economic Activity

Water prices and quotas and the ensuing surpluses to farmers and to water suppliers are all based on farmers’ behavior, summarized by these curves, as explained in Chapter 3 and analyzed in Chapter 4.

Country ↔ District or Perimeter Links

Economywide policies have direct and indirect effects on the supply of irrigation water by districts or perimeters and on the demand for irrigation water by farmers. The state sets water laws and property rights as well as rules for trading these rights. It often also determines the volume and cost of water supply by investing in water projects and conveyance facilities. All these have direct effects on farmers’ water endowment, and hence on their water demand, and on the daily operation of water districts, and hence on the cost of water supply.

Figure 1-2. Irrigation Water: Derived Demand, Average Cost, and Marginal Cost

The government also operates extension services, invests in research and development, and spreads out innovation processes and new crop varieties, all of which will affect the agricultural production technology, thereby changing the derived demand for water. The example comes to mind of the Green Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, which involved the development and spread of high-yielding cereal varieties. This process changed agricultural production technology, as farmers switched to new varieties that were more capital, fertilizer, and water intensive, thereby changing their demand for irrigation water.

Another profound effect of the state on the interaction between districts or perimeters and farmers occurs through the prices of agricultural outputs and inputs determined in the wider economy and world markets. The general equilibrium analysis of Chapter 5 deals with the way output and input prices are determined in the wider economy, the way government policies affect these prices, and the way these changes affect the profitability of irrigated agriculture in general and the productivity of water in particular. Changes in prices trickle down to farmers and district managers, who take the prevailing prices as given in calculating derived demand for and supply of irrigation water. Notice that the arrow in Figure 1-1 points in both directions. That is because, when agriculture makes up a large part of the economy, policies that lead to a more efficient allocation of water also affect prices, foreign trade, and hence the rest of the economy.

For tractability reasons, the macroeconomic computable general equilibrium (CGE) analysis cannot be so detailed as to consider individual farms or even perimeters [in Morocco, for example, it goes down to the level of the Regional Agricultural Development Authority (ORMVA)]. For farmers and district managers, on the other hand, how prices are determined in the broader economy is immaterial, as they take prices as given in their calculations. Thus, macroeconomic (i.e., broad economy) and microeconomic (i.e., perimeters or farms) models each serve a different purpose but together give a coherent picture of possible effects on water allocation and pricing under various policies. Ignoring one part may lead to erroneous conclusions, and hence to wrong policy recommendations.

Structure of this Book and Main Results

This book consists of ten chapters—five theoretical and empirical chapters and five country cases. The literature survey in Chapter 2 summarizes most theoretical and empirical work on irrigation water pricing to date.

Chapter 3 discusses the economic principles underlying demand for and supply of irrigation water with the associated welfare concepts and derives the guidelines for allocation and pricing. The analysis starts from a simple production function with one crop and one factor of production—water, with a given supply. A derived demand analysis is applied. It then adds crops and demonstrates an extension to a case of a water district where various farmers grow different crops. The inclusion of various farmers allows consideration of income-distribution analyses. In addition, the dual approach is presented, which allows derivation of a demand curve for irrigation in actual applications.

Several water-pricing methods are then introduced and analyzed for efficiency, equity, and implementation cost. With these in mind, additional issues are raised and analyzed with regard to cost recovery, water quality, and intertemporal considerations. The chapter also mentions some economywide considerations, but only in a preliminary way, and is addressed more fully later, in Chapter 5.

Several guidelines resulting from the analysis in Chapter 3 are summarized below:

- Marginal cost pricing achieves efficient water allocation, in that it maximizes the joint surplus of farmers and water suppliers.

- Average cost pricing guarantees a balanced budget of the water supply agency but entails a loss of efficiency. Farmers carry the burden of the welfare loss.

- Block-rate pricing can be used to transfer wealth between water suppliers and farmers, while retaining efficiency.

- The costs of implementing a pricing method are part of the supply cost and should be included in the variable costs (VC) and/or fixed costs (FC) of water supply.

- From an efficiency standpoint, the desirable pricing method is the one that yields the highest welfare after accounting for implementation costs.

- Any charge intended to cover the fixed costs of water supply agency should be levied in a way that does not affect farmers’ water input decisions.

- Water prices have a limited effect on income distribution within the farming sector and are therefore a poor means of addressing income-distribution goals.

- The question of who pays for the fixed cost of water supply when suppliers’ operating profits fall short of the fixed cost can be determined according to income-distribution criteria. In developing countries, the urban population is richer than the rural population and may carry some of the burden of the fixed costs of irrigation water supply. They will receive some benefit in turn in the form of less expensive food products.

- When water derived from sources of different quality has different effects on crop yield (e.g., fresh, saline, or reclaimed water), each water quality is treated as a separate input and must be priced separately. The demand for each water quality depends on the available supply and demand for the other water types. In this context, all water types should be priced simultaneously.

- When irrigation water is derived from a stock source (e.g., lake, reservoir, aquifer) in an unsustainable fashion, for example, if the stock shrinks over time or the quality of its water deteriorates, the price of water must also reflect the scarcity (i.e., depletion effect) and stock externality (i.e., effect of stock size on withdrawal cost). These effects show up through the user cost of water, calculated within an intertemporal management framework. The user cost of water should be added to the cost and price of water.

Chapter 4 investigates the practice of water pricing in five countries (Morocco, China, Mexico, South Africa, and Turkey) and evaluates efficiency and equity performance of water pric...