This is a test

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The last of the Ptolemaic monarchs who ruled Egypt for 300 years, Cleopatra is the most famous of the Ptolemaic queens. But what of her predecessors? The Last Queens of Egypt examines the roles played by the Ptolemaic royal women and explores their part in religion, politics and court intrigue. Explaining their propensity for incest, murder and power, Sally Ann Ashton shows the extent of the power they enjoyed, the price they paid, and how they shaped Cleopatra's reign.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Last Queens of Egypt by Sally-Ann Ashton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

Role models

The ideological and religious roles of Egyptian queens

In a world that was dominated by the male pharaoh, it is often difficult to comprehend fully the roles of Egyptian queens. A pharaoh would have a number of queens, but the most important would be elevated to ‘principal wife’. Titles that were adopted by queens often indicated a political or social as well as religious standing. There are two modern publications that list titles of the principal members of the royal family. The first is a compendium of the titles and names of Egyptian rulers that was published in 1916 by the French Egyptologist Gauthier, in five volumes, and called Livre des Rois. More recently Troy explored the roles of queens and the meaning of their titles, presenting an interpretation of what it was to be an Egyptian queen, and various other publications, such as Robins’ Women in Ancient Egypt, include a chapter on queenship, considering some of the better-known royal women. There has been one major and notable exhibition on Egyptian women, which has also included some queens but when we consider how many individual publications and special exhibitions there have been on pharaohs of Egypt there is somewhat of an imbalance. Part of the reason for this lack of interest in Egyptian queens is that, compared to their male consorts, we know little about them, either historically or in terms of their presentation. What evidence we have reveals not one, but several important roles that the Egyptian royal women fulfilled. One important point to note is that there is no word in Egyptian for queen. In the Ptolemaic period the Greek word Bassilisa (which translates as queen) was used for the royal women. The term ‘queen’ will be used in an Egyptian context here for convenience and ease of reading, but in Egyptian terms, as we shall see from the various roles of royal women, it is not an easily definable concept.

The mother of the pharaoh

Without doubt, one of the most important aspects of queenship was the role of mother of the pharaoh, and in this capacity the queens of Egypt became associated with the goddess Isis, who was mother of Horus, who was in turn represented on earth by the living ruler. Neithhotep was the first named Egyptian queen of the 1st Dynasty (3000–2890 BC) and her name appears in association with two early kings, Aha and Djer, to whom she is thought to have acted as regent. Queen Meritneith was also associated with king Djer, king Djet and king Den, of whom she was possibly the mother. On seal from Abydos, and now in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, Meritneith appears as ‘king’s mother’. Her importance is illustrated by the size of her tomb at Abydos, which is equal to those of the kings. That a woman was able to hold such a position in the 1st Dynasty is important for our understanding of the early role of Egyptian royal women and the continuity of association with the male rulers.

A 6th Dynasty statue, dating to the reign of Pepi II (2278–2184 BC) and now in the Brooklyn Museum of Art, clearly illustrates the role of the queen as ‘king’s mother’. The queen, Ankhnesmeryre II, sits with her son, Pepi II, on her knees; on the base of the statue the queen is described as ‘mother of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the god’s daughter, who is revered, beloved of Khnum’. Pepi II was about 6 years of age when he succeeded to the throne and his mother, Ankhnesmeryre II, enjoyed a prominent position, appearing with and associating herself with the king by means of her titles; thus justifying her role through the male members of the dynasty. This position of mother and son was later adopted for representations of Isis with her son Horus. Such images are extremely common from the New Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period, and are also adopted by Romano-Egyptian artists in the first century AD. The concept and image are not dissimilar to the later Christian Madonna and child.

The phenomenon of a former queen of a pharaoh being promoted as mother of a new pharaoh from the time of the 1st Dynasty demonstrates that from early Egyptian history there were defined roles for royal women. Indeed, when she outlived her consort and was replaced in that primary role by the new queen of the new pharaoh, the queen mother occupied a recognised position within the royal court. In many cases the role of a royal woman was dependent upon the ruler, hence the titles ‘king’s mother’, ‘king’s sister’ and ‘king’s wife’. None of these positions seems to have been fixed and there are huge discrepancies between individual women, sometimes as a result of a poor historical record, but in other cases because the individual stands out in terms of a religious or political role. The same is true of the Ptolemaic queens, and for each category of this period there is an earlier role model. In some instances, as we shall see, Egyptian artists refer back to images that were made 1000 years previously in order to distinguish between the various roles that the Ptolemaic royal women fulfilled.

Divine queens and their symbols of status

There are two methods of tracking the ideology of queenship: firstly, through the study of images and attributes and, secondly, by the titles they adopted. In addition to being linked to the king, queens were also associated with gods or goddesses, either through their titles, for example ‘daughter of Geb’, or in a role that linked them to a specific deity such as ‘god’s wife of Amun’. It is important to explore these links further to obtain a clear understanding of later associations between the Ptolemaic queens and divinities, and indeed their own divine status. In most instances associations were intended to elevate the status of the individual, and although this is true for all periods it seems to reach almost impossible heights during the reign of Cleopatra III, when the queen herself was worshipped as a goddess in her own right and honoured with five out of nine of the eponymous cults of Alexandria, as a goddess in the dynastic cult with her consort, and also as the personification of Isis.

The status of a queen was marked by the uraeus or cobra, which they wore on their brow. The uraeus was a protective symbol, initially worn on the crowns or headdresses of the pharaoh, and, by association, the queen of Egypt; it was associated with the sun god Ra and usually appeared as a single figure. It has been suggested that the uraeus may also have been linked to female deities and the solar myth, particularly with Hathor as the eye of Ra. From the 6th Dynasty the queen sometimes wears a vulture head with a cap depicting the wings and tail. This particular symbol is usually associated with divine images, and appears on certain occasions on representations of royal women, certainly until the end of the New Kingdom. Its use in the Ptolemaic period is not as straightforward and will be discussed further in Chapter 5. The cobra and vulture also represent the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt and as a hieroglyph the cobra was used as a determinative for goddesses.

However, from the time of the 18th Dynasty (1550–1069 BC), some queens wore a double uraeus. The earliest appearance of the double form was on the statues of an 18th Dynasty queen, called Isis, who was the wife of Thutmose II (1492–1479) and mother of Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC); it is used in conjunction with the title ‘mother of the king’. The double form of the motif is most consistently found on images of another 18th Dynasty queen, Tiye, who was the consort and principal wife of Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC), and mother of Amenhotep IV, who is perhaps more familiar as Akhenaten, the heretic pharaoh (1352–1336 BC). On the double uraeus of Tiye, one cobra wears the crown of Upper Egypt and the other the crown of Lower Egypt; on some of her statues the cobras are divided by a vulture, thus illustrating her divine status as well as that of queen of the two kingdoms of Egypt. When Amenhotep IV came to the throne his mother was still alive, and so to distinguish between the mother of the king and the wife of the king, the latter, Nefertiti, initially wore a single uraeus on her brow. It was not long, however, before Nefertiti was shown with the double uraeus, although interestingly only on a small number of representations, perhaps indicating a specific role or event in the royal court. The uraei of Nefertiti are never shown with the crowns of Egypt, but the queen did adopt the title ‘lady of the two lands’ – in other words, Upper and Lower Egypt. Nefertiti’s uraei, and indeed those of her successor Meritaten, are adorned with sun-disks and cow’s horns. The double uraeus appears again on images of the 19th Dynasty queen and daughter of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC), Meritamun. The Third Intermediate Period queen Shepenwepet I, who also wore the sun-disk and cow’s horns – perhaps stressing a link between the uraeus and Hathor and the eye of Ra – was chosen to be ‘god’s wife’ by her father Osorkon II (874–850 BC). This associated the women with the god Amun and elevated their status to that of a god’s consort. In this role they are shown with a vulture headdress, often in the embrace of the god. In contrast, the 25th Dynasty queen Amenirdas, who ruled in the eighth century BC, wore simply the double cobras, but also on occasion the vulture headdress, stressing her personal divinity. Like Shepenwepet I, Amenirdas held the title of ‘god’s wife’.

Because of the discrepancies in both titles and attributes which are associated with the double form of cobra, it is probably fair to conclude that it was used as a means of distinguishing a particular royal female, usually the principal wife, from others in the royal court. The later association with the god Amun is of particular relevance for the motif’s reappearance in the Ptolemaic period and was probably used here to stress the divine link between queen and god. The doubling of a recognised attribute is a clever way of highlighting an individual or portraying the individual in a specific role. One has to remember that Egyptian kings had more than one wife, and also that the mother was often still alive on his succession to the throne. Traditional artistic and ideological canons limited the variations upon a single theme, and so artists – and probably priests, in the role of advisers – were forced to turn to familiar symbols by which to express themselves or, more to the point, to allow the image to be readable.

The Amarna royal women as forerunners of the Ptolemaic queens

The women of the Amarna period were in many respects closest to those of the Ptolemaic period because of the changes in the role of both pharaoh and royal wife, which had begun during the reign of Amenhotep III and queen Tiye. As previously noted, Tiye played both a supportive and active role in the presentation of the royal family and was distinguished from other royal women by her double uraeus and vulture headdress. In addition to Amenhotep IV, who later became Akhenaten, Tiye gave birth to four daughters of whom we have a record: Sitamun, whose name translates as ‘daughter of Amun’; Henut taneb, who has a title meaning ‘mistress of all lands’, and is shown as a goddess on the colossal statue of the family from Medinat Habu, wearing a vulture headdress; Isis, who was obviously named after the goddess and who also adopted the title ‘king’s wife’; and Nebet ah, who was also named from a title meaning ‘lady of the palace’. Here, it becomes apparent why Tiye should wear the double uraeus: it is to distinguish her from her daughters. It was Tiye, however, who was to have a lasting impact on the next phase of royal history and indeed frequently appears in the historical record following the accession of her son, moving from the role of principal wife to that of king’s mother.

The 1996 catalogue for the special exhibition, The Royal Women of Amarna, offers a comprehensive overview of the women from this period. It is, however, worth considering a synopsis of the women and their roles. Nefertiti’s full name is Nefernefuraten-Nefertiti, meaning ‘the perfect one of Aten’s perfection’, ‘the beautiful one is here’. For her titles Nefertiti was described as ‘sweet of love’, ‘lady of all of the women’; others associated her with Akhenaten, such as ‘she is at the side of Akhenaten forever just as the heavens will endure, bearing that which is in it’ and ‘great wife of the king whom he loves’. She was also associated with gods ‘daughter of Geb’, and given more traditional titles such as ‘mistress of the two lands’. Her role was, in many respects, similar to that awarded to the early Ptolemaic queens. Nefertiti was not, however, Akhenaten’s only wife: the ruler also appeared with a woman named Kiya.

Nefertiti and Akhenaten had six daughters together. Some scholars have suggested that the king married at least one because of her title of ‘king’s chief wife’, her position on relief representations, which is closest to her father and also because her name and image eventually replaced those of Kiya. Another of the sisters, Ankhesenpaaten, was also possibly married to Akhenaten, and was later the wife of Tutankhamun. Her character is perhaps reflected in the request that she wrote, following Tutankhamun’s death, to a Hittite ruler asking for a suitable consort to be sent to her, with whom she could rule. From documentary evidence we know of other wives of the Akhenaten, whose names appear in documents but who were probably not depicted in sculptural representations. Here, Nefertiti and their daughters prevailed.

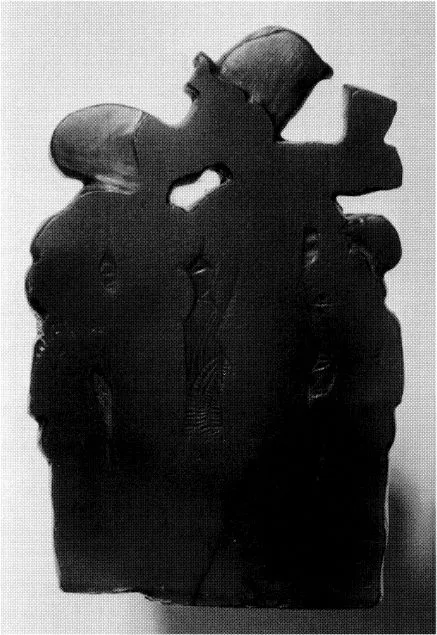

This observation is at least partly due to the manner of worshipping the Aten, or light of the sun-disk, during the Amarna period, which could only be accessed through the royal couple Akhenaten and Nefertiti. As a consequence of this change in the theology of ancient Egyptian religion, the queen and her consort appear on all relief representations worshipping the Aten. When compared to other Egyptian royal scenes, the Amarna period produced unusual groupings, which show the closeness of the royal family, illustrated by an unfinished gem in the Fitzwilliam Museum, where the royal couple embrace, their daughters at their sides (Figure 2). It has been suggested that Nefertiti took the name ‘the perfect one of the Aten’s perfection’ before the royal court was moved to Akhetaten or Tell el-Amarna, which is the modern Arabic name for the site. If this is the case, then Nefertiti may have been instrumental in one of the most innovative developments in the religion of ancient Egypt – indeed, not until Christianity arrived would such dramatic changes be seen again. There is, however, possibly more to Nefertiti’s role than chief wife and mediator of the Aten. Some scholars believe that Nefertiti became co-regent with Akhenaten and indeed outlived him, changing her name, which would explain its disappearance from the historical record. She appeared on the corner of the sarcophagus of Akhenaten as a protective goddess wearing the double uraeus, but given the status of her predecessor, Tiye, during her lifetime and her own elevated status, such an appearance, while still living, would have been acceptable. There is considerable documentary evidence to support the idea of a co-regency but some scholars remain sceptical of both the identity of the female and indeed if there ever was a co-ruler.

Figure 2 An unfinished gem showing Akhenaten and Nefertiti and their daughters embracing. (Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge EGA.4606. 1943; copyright and reproduced with permission of The Fitzwilliam Museum.)

Certainly, of all of the Amarna family, two women – Tiye and Nerfertiti, the two principal wives – are the most similar to their Ptolemaic counterparts. Both queens, as noted, were distinguished from other members of the female royal house by their attributes, in the case of the double uraeus, and also for the number of representations either as part of the king’s presentation or alone. The queens also appear with their off-spring, thus forming a family alliance and promoting their daughters from an early age. In the case of Nefertiti, the queen’s image was as carefully planned as that of her consort. The famous bust of Nefertiti from Tell el-Amarna, and now in the Egyptian Museum, Berlin, is a sculptors’ model that was found in a royal workshop; it was abandoned by the artists when they left the city early in the reign of Tutankhamun. The existence of such a model suggests a careful attention to detail and to the dissemination of the queen’s image. For the most part the images of Nefertiti follow the same three stages that were identified by Aldred: grossly exaggerated, less exaggerated and then idealised. Nefertiti’s early images are masculine in that they copy that of Akhenaten, and we find a parallel for this in the images of Cleopatra III which copy those of her sons, resulting in what appears at first sight to be a man in a woman’s attire.

Late period royal women

Among the late Egyptian female rulers the closest parallels to the Ptolemaic queens are the 25th Dynasty women. This dynasty is often referred to as the Kushite, because the queens ruled in the kingdom of Kush, modern Sudan, and so like the Ptolemaic queens they were foreigners. Amenirdas I, the sister or half-sister of the ruler Piy (747–716 BC) was installed as the ‘god’s wife of Amun’ at Thebes. Scholars believe that Amenirdas I was the aunt of Piya’s successor and the family continuity of the role of ‘god’s wife’ is expressed through her successor, Piya’s sister Shepenwepet II.

Titles and power were often associated with a specific role, as illustrated by those adopted by Nitokret ‘god’s wife’ of the 26th Dynasty, the daughter of Psammeticus I and Meketenusekht. Nitokret was called ‘beloved of Amun; the daughter who is created by Atum; hand of the god; she who adores the god; first priestess of Amun, the one who pacifies Horus with her voice, sister of the king, daughter of the king and the female Horus’. Divine association was among the first Egyptian traditions adopted by the Ptolemies and for this reason the royal women were extremely useful in the promotion of the dynasty and so the pharaoh. The problem for the Ptolemaic men, however, was that by the second century BC the women started to believe in their own divinity and, as a consequence, political power.

Whether they were aware of their predecessors we cannot know. Manetho, the Egyptian historian working at the Mouseion in Alexandria, chronicled the Egyptian kings, but whether the young princesses were read stories of the powerful queens of Egypt must remain speculative. Cleopatra VII was well educated, as illustrated by her command of several languages, and during the Ptolemaic period there becomes an increasing closeness between the royal family and the Egyptian priests. The possible re-use of an Amarna statue at Karnak is suggestive, given the connection between the royal women who were 1000 years apart. The statue was found at the Karnak temple, close to the Roman chapel; it is now housed in the Karnak Museum. An 18th Dynasty date has been suggested for the original statue, which was much later inscribed with the cartouche of Cleopatra II. The representation is preserved from the abdomen to the lower thighs and only the last few characters of the cartouche have...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Map

- Introduction

- Note on text

- Chapter 1 Role models

- Chapter 2 Egypt and the Ptolemies

- Chapter 3 Cleopatra and her ancestors

- Chapter 4 Presentation to the Greeks: Hellenistic queens

- Chapter 5 Continuing the tradition: queens of Egypt

- Chapter 6 The royal cults: deification and amalgamation

- Chapter 7 The legacy of the Ptolemaic queens

- A selective family tree of the Ptolemaic queens

- Bibliography and sources

- Index