This is a test

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sociology Looks at the Arts

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Sociology Looks at the Arts is intended as a concise yet nuanced introduction to the sociology of art. This book will provide a foundation for teaching and discussing a range of questions and perspectives used by sociologists who study the relationship between the arts – including music, performing arts, visual arts, literature, film and new media – and society.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sociology Looks at the Arts by Julia Rothenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE ARTS AND THE SOCIOLOGICAL IMAGINATION

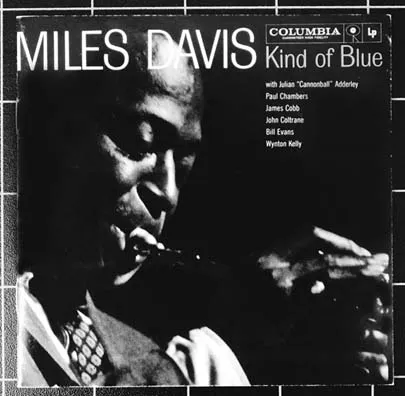

Photo 1.1 Kind of Blue, Columbia Records.

When I was a teenager in the 1970s, I would occasionally listen to records from my parents’ LP collection (those were the plate-sized plastic disks in the colorful cardboard sleeves, sometimes accompanied by thin books of song lyrics, pictures of the musicians and other kinds of notes). While the scratchy old recordings of Spanish Civil War songs and the weighty dissonance of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913) didn’t interest me much, I was continuously drawn to an album entitled Kind of Blue by the jazz trumpeter Miles Davis. At the time, I didn’t know much about the social history of jazz and its complex relationship to slavery and racial segregation in the United States. I knew even less about the evolution of avant-garde art music and the interaction between classical and jazz forms of musical structure. I knew nothing about the recording industry or other social institutions and technologies responsible for producing this and other jazz albums. I was unaware of the demographics of the jazz audience or the sales of this sort of album (in fact, Kind of Blue, released by Columbia Records in 1959, achieved triple platinum status in 2008, and Columbia touts it as the best-selling jazz recording of all time). That this album could be understood as a window to history and society only occurred to me much later, after I began to study sociology. What I knew was that when I listened to Kind of Blue, I was transported to another kind of reality, dominated by haunting sounds, which inexplicably sparked off a range of intense and compelling emotions and sensations.

This experience is probably familiar. Most of us derive great pleasure, meaning, and satisfaction from literature, music, painting, or other forms of art. For some, the arts provide a catalyst for spiritual and transformative experiences. For others, they are a safe haven from which to retreat from the noise of everyday life. The French painter Henri Matisse captured this sentiment well when he said: “art should be something like a good armchair in which to rest from physical fatigue” (Matisse in Flam, ed. 1995). Sociology and related disciplines of cultural and social analysis, on the other hand, study just those dimensions of life—social inequality, ethnic and racial divisions, and crime to name a few—that we often want to escape from through art. It asks us to put our tendency to insist on rational consistency, and material proof that an event or phenomenon is “real,” aside to experience its inconsistent, inexplicable, and fantastic reality. Conversely, the social sciences try to explain the social world by using the tools of science, systematic observation, and sustained analysis to understand how society works and identify the consistent patterns of social interaction that shape social life and social change. Sociologists explain social reality, including things that seem to defy rational explanation, such as religion, romantic feelings, and the arts, using theories and methods of the social sciences. While art asks us to suspend disbelief, the social sciences try to demystify the social world. These two modes of understanding—the social scientific and the aesthetic—may seem irreconcilable. Nonetheless, I hope to convince you that although we can explain emotional, mystical, or aesthetic experiences in terms of social patterns and structures, this does not eradicate the special qualities of these experiences or make them any less important or meaningful.

This book will provide you with strategies through which to understand and ask questions about the relationship between the arts and society while maintaining a respect for the arts as special forms of interaction through which we communicate experiences, knowledge, and feelings. We will explore art by activating what sociologist C.W. Mills (1959) called “the sociological imagination.” Mills defined the sociological imagination as

the capacity to shift from one perspective to another—from the political to the psychological; from examination of a single family to comparative assessment of the national budgets of the world; from the theological school to the military establishment; from considerations of an oil industry to studies of contemporary poetry. It is the capacity to range from the most impersonal and remote transformations to the most intimate features of the human self—and to see the relations between the two.

(Mills, 1959: 5)

I hope that this book will help you to recognize that what feels most personal, individual, and specific is also a product of history and collective systems of expression and interpretation and therefore shared by others. By recognizing the social nature of our experience, we may find a greater capacity to express ourselves through—and find meaning in—the arts.

Art Worlds

You will encounter repeated references to “art worlds” in this book. This term, popularized by the sociologist Howard Becker (1982), is useful because it gets to the heart of what the sociological imagination adds to our understanding of the arts. Art historians, critics, and other scholars from the humanities have traditionally focused on individual artists and works of art as well as genres, styles, and movements in their studies (Zolberg, 1990: 6). These aspects of the arts are only part of what interests sociologists and other socially minded researchers. Because sociologists regard aesthetic experience and meaning in relation to social interaction and social structures, they are interested in all of the social activity required to produce a work of art, not just the person who signed the painting, composed the music, or directed the film. As Becker explains, successful (and unsuccessful) works of art result from a collective process involving not only artists, but supporting personnel like critics, museum personnel, collectors, historians, publicists, and art consumers (Becker, 1982). The collaborative nature of art worlds may be fairly obvious in the case of music, theatre or film. After all, one person could not possibly do all the work to create a film like Avatar and every theatre performance requires different specialists: set designers, actors, publicists, sound technicians, and audiences.

From Becker’s perspective, even works of art that appear to be intensely personal, such as paintings or novels, are only possible through collective processes. For this reason, Becker argues that to understand the arts as a social activity (the focus of sociologists) we need to think not only about artists but also all the other people who are necessary to produce a work of art. If we cast a wide enough net, we sometimes have to include in our studies those people who might seem peripheral to the creation of works of art, like the spouses of artists who support them emotionally or financially, the workers in a musical instrument factory, or the chemists who discover new paint formulas. The complex web of social activity required to create an artwork composes an “art world.”

Defining the Arts: A Historical Perspective

It can be tricky and controversial to define what is meant by “the arts.” After all, the term arts is used in conjunction with a wide range of activities, including cooking, baseball, fashion, painting, singing, and stamp collecting. In the United States, we count among our national artists Steven Spielberg, Eddie Murphy, Meryl Streep, Jackson Pollock, Walt Whitman, and Jimi Hendrix. Each engages the human capacity for expressive, imaginative, and sensual experience. At the same time, we only think of some of these figures and the works associated with them as belonging to the category of “fine arts.” While the poet Walt Whitman’s affirmation of the human body and erotic desire, I Sing the Body Electric, is taught in literature classes, the comedian Eddie Murphy’s hilarious and touching performance in Raw, Uncut is not. The painter Jackson Pollock’s work is exhibited in fine arts museums while Steven Spielberg’s movies can be rented on Netflix. Art critics and other gatekeepers from within various art worlds often make what sound like definitive distinctions between fine arts and popular culture (i.e. the tenor Lucianno Pavarotti was a fine artist while Michael Jackson was a pop star) or try and rank the quality of individual art objects or artists against one another (i.e. Matisse was a more important painter than Picasso, or Macbeth a greater play than Romeo and Juliette). Sociologists, on the other hand, are not, at least as sociologists, interested in the “objective” validity or accuracy of such ranking systems. They are interested instead in the social processes through which ranking systems are created, accepted and reinforced, and the social processes that contribute to changes in these systems. How did the emergence of the dealer/gallery system for distributing paintings in France in the 19th century propel the commercial success of the impressionist painters? How did pop stars like Madonna, David Bowie, or Sinead O’Connor reflect changes to prevailing gender norms in the United States and Europe during the 1970s and 1980s? How do women’s social networks impact how they read and evaluate romance novels? These are the kinds of questions, as opposed to normative or evaluative questions, that sociologists are likely to ask. In addition to studying the role of social processes in the formation of the arts, sociologists are also interested in what these ranking systems, and the processes and objects associated with them, can tell us about society.

Sociologists analyze the historical and social processes through which the arts came to be viewed as a special category of cultural production in society. These processes are directly linked to the development of the sorting mechanisms that are employed to distinguish the arts from other kinds of cultural products and which assign value to those distinctions. It is not enough to know that works of art are the result of collective processes of meaning making. Those processes themselves take place within a larger social and historical context, which provides the parameters within which certain kinds of ideas and cultural activities emerge (Foucault, 1970).

As you will see, the formation of a distinctive sphere of fine arts was tied to the development of other categories, like folk art, popular culture, and mass culture that we use when we talk about culture. When scholars study art worlds, they often speak of popular culture and high art to indicate which type of art world they are studying. They don’t do this because one kind of art or cultural production is superior to another but rather because these are socially recognized labels. Sociologists understand that these categories emerged through a process of social construction and evaluation and they try to explain these social processes. In addition, the category of fine or high art is only meaningful in some kinds of societies and in relation to other categories of art, for example, popular and folk art or mass culture. Many of the examples I use in this book fall into the category of fine art. This is not because I prefer the avant-garde musical compositions of John Cage to the Beatles. We stick, primarily, to the fine arts of Western societies in this book because of space and time constraints and because many excellent books have been devoted to the sociological study of popular culture and non-Western and traditional arts. One author (or book) cannot adequately cover all of this ground.

Sociological Lenses

When photographers create an image, they choose a lens that is best able to capture the level of detail, the scope of coverage, and the angle or perspective that interests them. A photographer wishing to create an intimate portrait of her mother or the pattern on a butterfly’s wing will choose a lens that can focus up-close. Such a lens might capture details from a single subject or small group of objects but cannot focus on a sweeping landscape seen from a mountaintop or the crowds of people at a political demonstration. For these kinds of scenes, a photographer would choose a wide-angle, landscape lens. If the photographer wants to record the interaction of a small group of children playing on a jungle gym in a playground, she will choose a medium-range lens. Each lens in the photographer’s camera bag is useful for zeroing in on an aspect of reality, but no single lens can record both the fine lines on a subject’s face and the patchwork of farmland in the distance with the same level of clarity.

Photo 1.2 Skyline of Manhattan, Geoffrey Berliner. (Courtesy of Geoffrey Berliner)

Sociologists, including sociologists of art, are a bit like photographers in this regard. One sociological lens is useful for studying how violinists in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra manage the conflicting demands of competition with each other for seats and working together cooperatively as a section. This kind of lens can zoom in on face-to-face interaction between orchestra members. The same lens or, to put it more directly, sociological perspective, will not help a sociologist understand how or why the modern symphony orchestra developed in 18th century Europe or how the development of this institution was facilitated by the growth of other political and economic institutions of the period. For this, we need a wide-angle lens able to capture sweeping social and historical developments. What we miss with this lens, of course, are the intricate details of small-scale social interaction. We need yet a third, medium-range lens to study the organizational structure of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra or the relationship between the Orchestra and government funding institutions. Sociologists choose from an array of tools, methods, and perspectives to illuminate different levels of social reality. Some of these “lenses” allow them to focus on up-close, small-scale social interaction but are not useful for capturing large-scale social patterns and historical change and vice-versa. Ideally, sociologists can view their object of inquiry from a variety of angles and depths of field and make connections between small-scale or “micro” interactions and larger structural dimensions of society. In reality, however, sociologists, like everyone else, face time constraints, have individual preferences, and need to keep doing the kind of work on which their reputations are based and they may (like some photographers) stick with one lens for their entire careers. Even so, sociologists should be conscious of the way in which their lenses help determine the scope of their studies.

Photo 1.3 Fourth of July, Geoffrey Berliner. (Courtesy of Geoffrey Berliner)

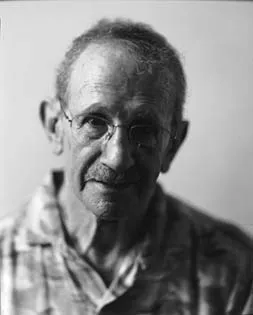

Photo 1.4 Portrait of Philip Levine. (Courtesy of Geoffrey Berliner)

Art in Society

Identity and Structured Inequality

When sociologists talk about social structures, they are referring to the range of social patterns, rules, and resources (Giddens, 1976, 1984) or “schemas” (Sewell, 1992) characteristic of any given society. Sociologists, using a variety of lenses, describe patterned types of social interaction, social roles and positions, social identities, inequality and resource distribution, social institutions and norms and values through which social activity is structured. Although sociologists argue about the degree to which social structures determine individual actions (see, Giddens, 1984, Sewell, 1992, Berger and Luckmann, 1966), most would agree that with any type of social activity (war, sex, food preparation, childrearing, dancing—to name a few) individuals choose their actions from a set of options that have already crystallized as social structure. As Karl Marx (1852) famously said “[m]en make their ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Arts and the Sociological Imagination

- 2. What are the Arts?: A Historical Perspective

- 3. Lenses of Analysis

- 4. Social Class and the Arts

- 5. Gender and the Arts

- 6. Race and the Arts

- 7. Art, Politics, and the Economy

- 8. Technology and Globalization

- 9. Artists and Their Work

- 10. Meaning and Interpretation: What Does it Mean?

- Bibliography

- Glossary/Index