![]()

The Nature of Violence and Threat Assessment

Over the past several years, concern over the safety of students in schools has increased. Much of this concern stems from media reports of several school shootings. From 1996 to 1999, highly publicized school-based shootings took place in Jonesboro, Arkansas; Littleton, Colorado; Moses Lake, Washington; Conyers, Georgia; West Paducah, Kentucky; Pearl, Mississippi; Springfield, Oregon; Edinboro, Pennsylvania; and Fayetteville, Tennessee (Task Force on School Violence, 1999). According to the Task Force on School Violence (1999) in New York State, twenty-five students and four teachers were killed and another seventy-two students and three school employees were wounded in these shootings. As a result, considerable debate has been given to the causes of school-based violence and the steps that should be taken to reduce such violence, improve school safety, and maintain security in educational settings.

School shootings are not confined solely to middle and high schools. In the early part of 2000, a six-year-old boy in Michigan found a semiautomatic weapon in the house where he had been living with his mother and uncle. The house had been known to local authorities as a place where guns were often traded for crack cocaine. One day after a reported scuffle on the playground, the boy brought the gun to school and fatally shot a first-grade classmate. This tragedy illustrates that violence in schools is a social problem that spans all ages and grade levels.

These events have generated considerable concern among politicians, law enforcement personnel, mental health professionals, the general public, and school officials. Although the problem is multi-faceted and a clear understanding of the causes and precipitants of school violence is complicated by the vast number of factors that must be considered, a pressing need exists to address this issue in light of a recent increase in multiple-victim, highly lethal shootings.

To illustrate the complexity of the problem, it may be useful to examine some of the more highly publicized school shootings that have occurred in recent years. Verlinden, Hersen, and Thomas (2000) examined several key groups of variables that were associated with these incidents, including individual, family, school/peer, social, situational, and attack-related behavioral factors for nine cases of multiple victim shootings in the three years prior to their study. Most major incidents were included in their sample, including Moses Lake, Washington (Barry Loukaitis); Bethel, Alaska (Evan Ramsey); Pearl, Mississippi (Luke Woodham); West Paducah, Kentucky (Michael Carneal); Jonesboro, Arkansas (Mitchell Johnson and Andrew Golden); Edinboro, Pennyslvania (Andrew Wurst); Springfield, Oregon (Kip Kinkel); Littleton, Colorado (Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold); and Conyers, Georgia (Thomas Solomon).

According to a detailed analysis of these cases, Verlinden and her colleagues found that most of the offending youths had a history of emotional disturbance, including depression and anger, a history of aggression, and previous threats of violence. Over half of the youths had generated drawings or writings that had violent themes; moreover, suicidal threats or ideation were very common among school assailants, while impulsivity was not. The attacks were carefully planned. Most of the youths either lacked parental supervision or had families in which there was considerable disruption, including a lack of support and a history of abuse or neglect. Moreover, many of the youths were socially isolated, rejected by peers, and had poor social skills. They often associated with peers who had conduct problems. In all of the cases, the youths had easy access to a gun, and most were fascinated with firearms and explosives. Many had extensive interest in video games, music, and other media that involved graphic violence. Furthermore, some of the youths showed evidence of deterioration in their functioning just prior to the attacks. Particularly notable was the fact that all of the youths clearly communicated their violent intentions to others and some even foretold the time and place the attacks would occur.

These findings illustrate that school violence is a problem that encompasses psychological, environmental, family, and situational factors; simple causal explanations are not possible. Furthermore, research into the dynamics of these cases is extremely useful because it expands our understanding of the unique factors that are associated with school violence and informs our efforts at prevention. There are different and sometimes conflicting approaches to applying research on school violence, however. One approach to using this applied research is to formulate “warning signs” of violence or profiles of the potentially lethal student, with the typical goal being removal of the student from school. Another approach may be to respond to threatening behavior in a manner that minimizes the potential for harm to others.

This guide is intended to be used by professionals who are in a position to evaluate and manage threatening behavior by students in school settings. It is intended to provide an approach to managing potentially violent situations in a manner that is interdisciplinary, preventive, and based on psychological concepts and principles. In this chapter, the prevalence of school violence will be examined and various approaches that have been set forth for dealing with the problem will be discussed. In addition, a critical analysis of many popular policies that are limited in their ability to prevent violence will be provided. Finally, an approach to evaluating and managing threatening behavior in school settings will be outlined, one that is based on a model of threat assessment and management whereby specific behaviors are targeted and a comprehensive evaluation and management plan is developed. The remainder of this guide will specify this approach in greater detail, including a discussion of various types of threats, how they are communicated, risk factors associated with violent behavior, ways to assess and manage threats, and special situations where potential for violence exists.

VIOLENCE IN SCHOOLS

Although violence among young people is a serious concern in society, one of the primary concerns in recent years has been the safety of children when they are at school. Between 1992 and 1994, seventy-six students were murdered or committed suicide while in school, according to data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (Kaufman et al., 1998). During the 1996–1997 school year, 10 percent of public schools had at least one incident of serious violence that resulted in a report being made to the local police or law enforcement agency. Despite public concern over safety in schools, data show that if a student is the victim of violence, it is more likely to occur away from school rather than while the student is on school grounds. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 1996, 255,000 students between the ages of twelve and eighteen were the victims of some nonfatal violent crime (e.g., rape, assault) and 671,000 students were victims in violent incidents that occurred off school grounds. Moreover, most murders and suicides involving children and adolescents occurred while the victims were not at school.

Although these statistics support the notion that more violent incidents involving children and adolescents occur away from school than at school, violent incidents in school settings continue to cause alarm regarding the safety of students. Schools are generally viewed as places where children should be safe and secure to facilitate their learning and growth. The fact that a young person is more likely to be the victim of violence away from school does not automatically lead to assurances that students will be safe at school. Between 1989 and 1995, for example, the number of students who feared being attacked or harmed at school rose from 5 percent to 9 percent, which represents an increase of about 2.1 million students over this six-year period (Kaufman et al., 1998).

According to research by Verlinden, Hersen, and Thomas (2000), the number of violent deaths in school settings since the 1992–1993 academic year has steadily decreased. However, violent incidents involving multiple victims has increased. Between 1992 and 1995, there was an average of one violent school-based incident involving multiple victims each year, whereas between 1995 and 1999 there was an average of five such incidents per year. Therefore, while school violence may be declining in some respects, more highly publicized lethal incidents involving several victims may be contributing to increased concerns about school safety.

APPROACHES TO COMBATING SCHOOL VIOLENCE

Many policies and programs have been proposed or implemented around the United States to deal with the problem of violence in the schools. Among the more visible and popular attempts are the use of metal detectors at entrances, banning bookbags, stationing police officers or security guards at school entrances, and installing video monitors and other security equipment. Another highly publicized change has been implementation of “zero tolerance” policies for managing school violence in which any behavior, threat, or gesture that is remotely indicative of potential violence results in the student being immediately suspended or expelled from school. In some instances, the use of zero tolerance policies has resulted in questionable responses to supposed threats as some students, who write poems or short stories with violent themes and submit them as part of a formal school assignment, are identified as a threat and suspended from school.

Other approaches to dealing with school violence include the passage of legislation that seeks to increase punishment for those who commit acts that pose a risk to others. For example, some states have passed laws calling for mandatory incarceration for one year or more if a student brings a gun onto school grounds. In other instances, legislation has been proposed to make parents criminally liable for the actions of their children. Many of these legal mandates seek to set up strong deterrents that are believed to reduce the risk for future school violence.

Several problems exist with many of the approaches that have been either implemented or proposed for dealing with school violence. For example, zero tolerance policies are essentially unproven with respect to their ability to prevent violence because they fail to target situations where a student does not make a threat, or threats are not known to school officials, and the student later commits an act of violence. In other circumstances, laws that make parents criminally liable for the acts of their children impose a punishment “after the fact,” where violence has already occurred. Clearly, the most desirable approach to threatening behavior and violence in schools is to prevent harm before it occurs.

Another popular approach to addressing the problem of school violence is heightening awareness of the “warning signs” of violence. In particular, printed material and published literature is often circulated to sensitize parents, teachers, school administrators, and others to the emotional and behavioral indicators that suggest a specific student may represent a heightened risk for becoming violent. This particular approach raises serious questions about the problem of erroneous or inaccurate judgments being made about some students.

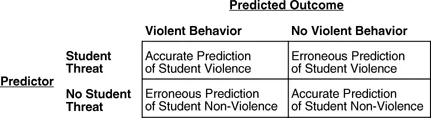

The prediction of violent behavior based on a specific indicator that is believed to be associated with violence, namely a clear threat, can be conceptualized according to a basic contingency table as outlined in Figure 1.1. This grid is similar to others that have been utilized in the field of violence prediction (Quinsey et al., 1998). When the presence or absence of a student threat is used to make a decision on an appropriate course of action, four possible outcomes can occur. The student who makes an overt threat and ends up committing a violent act is represented by the upper left quadrant in which there has been an accurate prediction of violence based on the threat. However, if the student makes an overt threat but has no intention of carrying out the threat and does not end up becoming violent, then a false alarm error has occurred in which a prediction was made that a nonviolent student will become violent. This situation is represented by the upper right quadrant of Figure 1.1 and illustrates that someone who makes an overt threat may not necessarily pose a threat of violence (Fein, Vossekuil, and Holden, 1995).

Two other outcomes are possible if a student does not make an overt threat. The lower left quadrant represents a situation in which the student does not make an overt threat but commits an act of violence. This judgment involves relying on the absence of a threat to make the determination that a student will not be violent. In some cases, however, the student may conceal his or her intention of doing something violent, but may exhibit other indicators of violence potential that are missed if reliance is placed solely on the presence or absence of an overt threat. This situation results in an erroneous prediction of nonviolence, which highlights the notion that someone who poses a real threat of violence may not necessarily make a threat (Fein, Vossekuil, and Holden, 1995). Finally, the lower right quadrant of Figure 1.1 represents an accurate prediction of nonviolence based on the absence of an explicit threat.

FIGURE 1.1. Decision Accuracy for Predicting Student Violence

This model of predictive decision making reflects many of the problems that are inherent when relying on any single predictor of violence, such as when a threat is relied upon to make a judgment about future violence. If this model is applied to zero tolerance policies, for example, a threat made by a student, even if done jokingly or without any intent or means for carrying it out, would result in the expulsion of the student based on the notion that all students who threaten are considered potentially violent. As a result, two types of errors will be made under threat management strategies in schools that adopt zero tolerance policies. Some students who threaten yet never act violently will be incorrectly viewed as violent. Likewise, students who do not threaten yet later become violent constitute an erroneous prediction of nonviolence and are not identified under zero tolerance policies. Moreover, it is likely that schools with a zero tolerance stance do so to demonstrate to school boards, the public, and governmental agencies that they have a method for dealing with school violence. However, such policies are prone to error if the complex relationship between threats and violence is not recognized.

Many of the policies and procedures that have been implemented for dealing with school violence, such as zero tolerance or enforcing stricter criminal penalties for youngsters who bring a weapon to school, arise out of a need to respond to the risk of violence in schools. These policies create an appearance of reasonable and well-intended responses that may provide some reassurance to students, their parents, and the community. However, they can be faulted for several reasons, including the fact that they have not been tested empirically, intervene after the fact, or result in critical errors when identifying those students who actually pose a threat to others.

One approach to managing school violence that holds considerable promise for dealing with threatening behavior among students is the threat assessment model developed by the United Stat...