eBook - ePub

Eating Disorders And Marriage

The Couple In Focus Jan B.

This is a test

- 231 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Eating Disorders And Marriage

The Couple In Focus Jan B.

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume should enhance health care professionals' understanding of the myriad complications that develop when a person with an eating disorder gets married or becomes involved in a long-term intimate relationship. Drawing on their vast experience in family therapy, social work, and treatment of eating disorders, the authors carefully review the current literature on eating disorders in long-term relationships, and then present a practical approach to assessment and treatment.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Eating Disorders And Marriage by D. Blake Woodside, Lorie F. Shekter-Wolfson, Jack S. Brandes, Jan B. Lackstrom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Psicología anormal. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Overview of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

This chapter introduces the eating disorders anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) to those who have not been trained in their treatment and etiology. The conceptual framework presented has guided the development of our marital interventions; therefore, even those with experience in the assessment and treatment of these disorders will want to review the section on etiology, in order to become familiar with our basic assumptions.

CLINICAL FEATURES

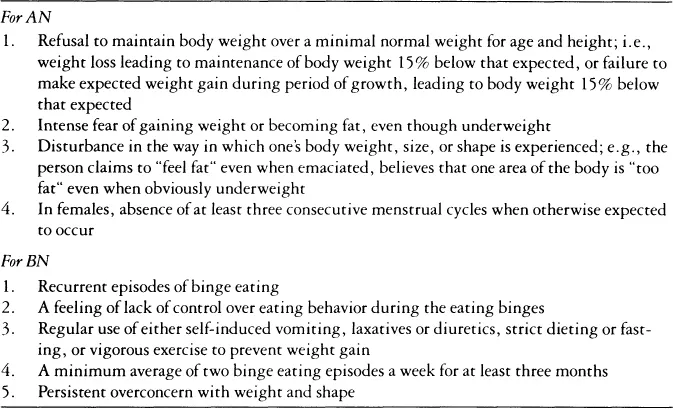

Table 1.1 presents the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for AN and BN (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). Anorexia nervosa is characterized by a relentless drive for thinness and by a body image distortion, which typically leads individuals to reach very low body weights. Patients may achieve these low weights by strict dieting, excessive exercising, or purging behaviors, such as vomiting or laxative use (Kaplan & Woodside, 1987).

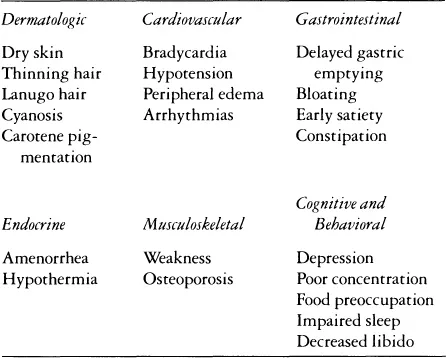

Many of the typical features of AN are closely related to the starved state, as has been demonstrated by the work of Keys et al. (1950) and more recently, Fichter and Pirke (1984). These features include the intense preoccupation with food that most anorexics experience, and physical symptoms, such as bloating, early satiety, bradycardia, and ammenorhea. Also included are many psychological changes, including irritability, lability of mood, depression, and exacerbations of premorbid personality traits. Many individuals experience extreme social isolation as a consequence of their starved states. Table 1.2 lists some common side effects of starvation.

TABLE 1.1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by bingeing; that is, the consumption of large quantities of food in a short time. Clinicians occasionally confuse the presence of vomiting, a common symptom of bulimia, with bulimia itself: however, only about 80% of bulimics actually vomit, with the remainder purging through other means, such as laxatives, strict fasting, diuretics, or vigorous exercise. The typical eating patterns of most patients with BN include strict dieting between binges: some patients develop a chaotic eating pattern in which there are no periods of even relatively normal eating, but only continuous bingeing. In addition to bingeing, which must occur at a specific frequency, bulimics share with anorexics an intense preoccupation with weight and body shape. It should be noted that BN may occur at any weight, and that if it arises in the context of AN, both diagnoses should be made.

TABLE 1.2.

Common Side Effects of Starvation

Common Side Effects of Starvation

There are numerous complications of BN that are related to the bingeing and purging behaviors. Swollen parotid glands result from local irritation by hydrochloric acid during vomiting. Russell’s sign (Russell, 1979), a callus or sore on the back of the hand, is secondary to abrasion of the back of the knuckles during the manual induction of vomiting. Patients who vomit frequently may develop severe dental caries, as tooth enamel may be quite sensitive to the action of gastric acids. Lacerations of the esophagus may occur, resulting in blood in the vomitus. Bulimic patients tend to experience the same bloating as patients with AN, but may not have early satiety. Patients who abuse laxatives may experience alternating periods of diarrhea and constipation, and sometimes bloody stools. In extreme cases, individuals who use large quantities of laxatives may become laxative dependent, unable to have normal bowel movements without the aid of purgative laxatives.

Individuals who purge via vomiting, laxative abuse, or the abuse of diuretics may experience hypokalemia; that is, a low level of the body salt potassium. Critical for normal heart function, potassium deficiency can lead to death, sometimes with minimal warning, and so constitutes one of the most serious medical complications of AN or BN. It is imperative that the electrolyte status of actively purging bulimia nervosa patients be monitored regularly.

The chaotic eating patterns in BN have a variety of psychological effects, including lability of mood, sleep disturbance, decreased concentration, and irritability. These features occasionally can be confused with depressive episodes; the diagnosis of depression must be made with caution in the patient with active BN. Because of the profound effects of chaotic eating and starvation on mood, significant suicidal ideation may be seen in some patients.

Despite the above caution, there is considerable psychiatric comorbidity in these individuals. The majority of patients with BN will report a lifetime history of at least one episode of depression, and nearly 50% will have experienced difficulty with a substance, most commonly alcohol. Less frequent are the diagnoses of anxiety disorders or bipolar affective disorder. In our experience, the diagnosis of schizophrenia is rare in patients with either AN or BN.

Patients suffering from both of these disorders may experience very marked distortions in the perceptions of their bodies. These concerns tend to persist well beyond the point at which eating is normalized, most likely representing a major contributor to relapse. The concerns may be relatively unfocused, appearing to have little referent in the patients life, or they may be related very distinctly to particular traumatic events, such as childhood sexual or physical abuse.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Anorexia nervosa is thought to occur in approximately 0.5–1% of women aged 15–40 (Crisp, Palmer, & Kaluci, 1976). Rare cases of late onset have been reported (Hsu & Zimmer, 1988). Bulimia nervosa probably is found in a slightly higher percentage, perhaps as much as 1–2% of the same age grouping (Fairburn & Beglin, 1990). The symptom of binge eating is fairly common, in both men and women: however, this symptom alone should not be confused with the full-syndrome illness, which requires the excessive preoccupation with weight and shape described above.

Male cases account for about 5% of most series, with BN being much more prevalent than AN. The reason for the predominance of female cases is unknown, but may well relate to the differential dosing that men and women receive in terms of the cultural message to achieve slimness. It may also be that other, as yet undetermined, constitutional factors play some part. In any event, no significant differences have been demonstrated between male and female cases, and the two situations should be treated in the same manner.

ETIOLOGY

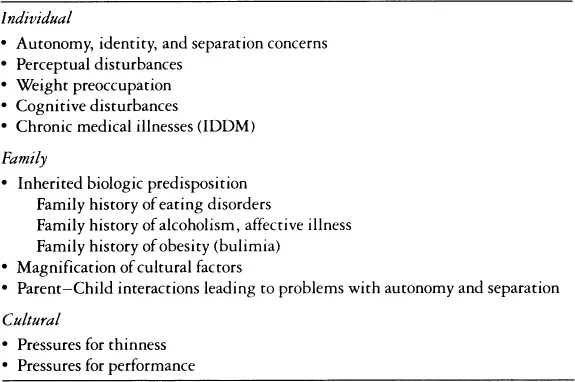

No definitive etiology has been demonstrated for either AN or BN. At present, a multidetermined model, such as that advocated by Garfinkel and Garner (1982), seems most appropriate in furthering our understanding of these complex conditions. In this model, each person experiences a range of specific predisposing factors, which may include all of the psychological factors, biological factors, social factors, and family factors. Some typical issues that are common antecedents to the development of an eating disorder are presented in Table 1.3. Dally (1984) believes that marital discord is an important precipitant for AN that develops in adult life. Common threads in these issues are a sense of impaired self-worth and a feeling of ineffectiveness or of being out of control. The model suggest that these feelings may lead some individuals to engage in dieting behaviors as a way to regain a sense of control and temporarily to elevate self-esteem.

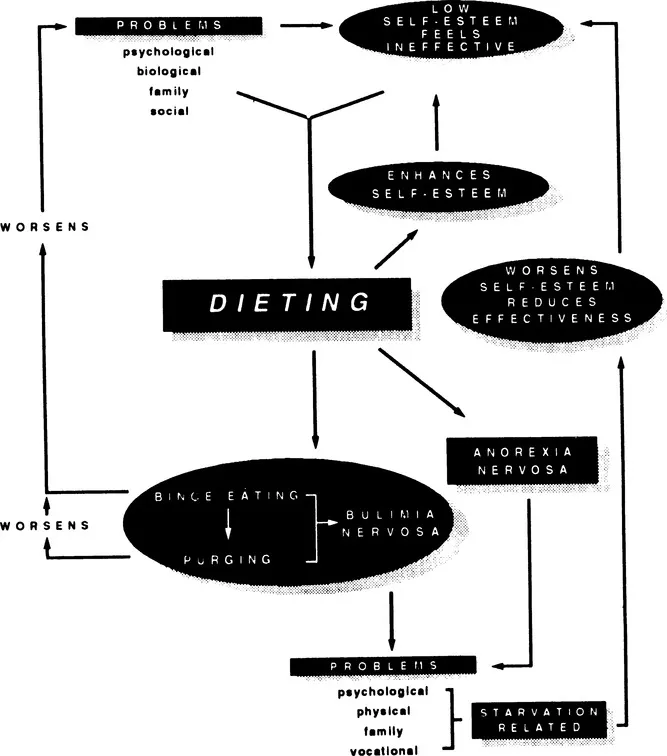

Unfortunately, dieting and losing weight are not likely to be an effective approach to resolving psychological difficulties in the long run. Figure 1.1 demonstrates the ways in which dieting behaviors become problems for patients with eating disorders. First, as the dieting behavior does not resolve psychological problems, it must continue for the individual to maintain a feeling of well-being. This factor in itself creates a vicious circle, as the effect of long-term dieting is almost invariably weight gain (for a review, see Ciliska, 1991, pp. 3–21). For a small percentage of individuals, ongoing dieting with continued weight loss to the point of emaciation occurs, resulting in AN. Many specific effects of starvation, such as bloating, early satiety, and ankle edema, may directly lead the patient with AN to restrain her food intake further in an effort to reverse the starvation effect. The severe effects of starvation and chaotic eating on the vocational and relationship spheres of these patients further contribute to their sense of ineffectiveness and low self-esteem. For example, many such individuals are forced to drop out of educational programs or to leave their jobs because of a lack of the ability to concentrate. Some of us (Woodside, et al., submitted for publication) have noted the effects of active eating on family functioning. Why certain individuals are able to continue to suppress their weight to this point is unknown, but it may well be the result of some hereditary component. Eventually, as a result of the profound effects of starvation on physical and psychological functioning, an individual with AN may come to treatment. However, it is rare for the core symptom of the illness, the drive for thinness, to be ego-dystonic at this stage; rather, the patient often will desire to be rid of the complications associated with the starved state while still wanting to remain very thin.

TABLE 1.3.

Common Antecedents to the Development of an Eating Disorder

Common Antecedents to the Development of an Eating Disorder

Figure 1.1. Formulation of Eating Disorders

More common is the development of bingeing in response to ongoing dieting. The work of Polivy (1976) on the determinants of normal eating strongly suggests a causal relationship between chronically restrained eating and bingeing behaviors. Once established, the dieting-bingeing cycle commonly will lead to purging behaviors or to stricter dieting to “undo” the effect of the bingeing. These behaviors, in turn, lead to increased starvation, and thus increased bingeing, facilitating the continuation of the cycle. And none of this contributes to a resolution of the initial psychological disturbance. In fact, once one has invested self-esteem into not eating, the development of binge eating is a devastating blow that, again, simply feeds into the cycle.

Viewed in this light, the application of models of addiction to the eating disorders becomes possible. However, it must be emphasized that food is not the addictive substance; rather, such individuals must be seen as having become addicted to dieting behaviors. It is these behaviors that must be targeted in treatment efforts.

In our opinion, the development of an appreciation of the connection between dietary restraint and eating disorders is an essential task for any professional who works clinically with patients suffering from AN or BN, regardless of the nature of the primary treatment that is being offered. Failure to have a clear understanding of these interactions may significantly impair the ability of a clinician to provide appropriate care for these patients. Needless to say, we do not support any treatment strategy that is focused on food avoidance, as such a strategy almost certainly will make both illnesses worse for the vast majority of patients.

ASSESSMENT OF THE EATING-DISORDERED PATIENT

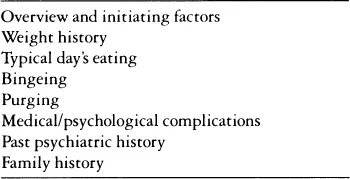

Table 1.4 presents the components that make up a basic assessment of the patient with an eating disorder. Interested readers may also wish to become familiar with structured diagnostic interviews for eating disorders, such as the Eating Disorders Examination (Cooper & Fairburn, 1987). Chapter 4 details more comprehensive assessment techniques pertaining to couples. Practicing family and/or marital therapists may see many patients who have been referred having already had a general assessment performed. When this is not the case, we recommend that the family/marital therapist either perform such an assessment or arrange to have an appropriate assessment done. The reasons for this are many. First, as reviewed below, we support a multidimensional model of treatment, as well as a model of multidimensional causation. Thus our expectation would be that at the same time that family or marital therapy was occurring, other treatment modalities would also be employed. We do not recommend family or marital therapy as the sole treatment modality for patients with active eating disorders.

TABLE 1.4.

Basic Components of the Assessment of a Patient with an Eating Disorder

Basic Components of the Assessment of a Patient with an Eating Disorder

Second, both AN and BN may result in serious, life-threatening medical complications. Therapists who are not physicians should not put themselves in a position of feeling that they are responsible for monitoring these complications when they neither are trained to do so nor have access to appropriate diagnostic facilities.

The assessment has two basic parts: assessment of eating behaviors and symptoms and assessment of other relevant information.

Eating Behaviors

Overview and Initiating Factors

Initially obtaining an overview of the history of the eating disorder is useful, as it will assist the interviewer in focusing his or her questions more effectively. Such an overview includes information on the initiation of dieting behaviors and significant changes that have occurred since. Beginning in this fashion also may shed significant light on the actual predisposing and initiating factors for the individual in question.

Weight History

A weight history is very important. It should be noted that a record of height is a significant component of such a history. Patients with AN more typically will have weight fluctuations between average weight and a low weight, whereas patients with BN may show dramatic fluctuations in weight both above and below average. It is important to get an idea of premorbid weight, and this may be a convenient time to glean some sense of the physical size of family members. This may also be an appropriate time to obtain a menstrual history from female patients, including the documentation of oral contraceptive use.

Typical Daily Intake

The cinician should attempt to assess a typical days intake for the patient. Some patients will be reluctant to disclose this information; others, especially p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Overview of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

- 2. Review of the Current L iterature on Marriage and Eating Disorders

- 3. Marriage and Eating Disorders

- 4. Assessment of the Couple

- 5. Brief Couple Treatment for Eating Disorders

- 6. Long-Term Treatment of Eating-Disordered Couples

- 7. Empirical Studies of Couple Functioning

- 8. Eating-Disordered Patients as Parents

- References and Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index