- 225 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Balancing Juvenile Justice

About this book

The juvenile justice system in the United States has become a detrimental rather than a remedial experience, one that often reinforces youths' defiance of authority. Trying juveniles as adults, overcrowding juvenile detention facilities, and other factors have led to the deterioration of a system whose original intent was to protect immature youngsters who might get arrested for truancy or joyriding. The present system is ill equipped to cope with today's children who may be arrested for violent crimes such as rape and murder. This has led to an intense pessimism. Balancing Juvenile Justice, now in an expanded, revised edition, is a comprehensive discussion of the primary considerations policymakers should use in striking a balance between holding youths responsible for past behavior, and providing services and opportunities so that their future behavior will be guided by constructive, rather than destructive, forces. The topics covered include: trends in philosophy and politics; a review of state and local reforms in juvenile justice; the changing role of the juvenile court; development of a balanced continuum of correctional programs; and strategies for reform. The authors emphasize that while juvenile offenders should pay for their crimes, it is equally urgent to realize that adult neglect, abuse, rescinding needed resources, and stigmatizing of youth will only ensure that crime and criminal justice become permanent distinguishing features of the United States. This new edition of Balancing Juvenile Justice will be compelling reading for sociologists, criminologists, juvenile justice practitioners, and policymakers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Trends in Philosophy and Politics

1.1 The Context of Juvenile Justice

Juvenile offenders are caught in a multi-causal and largely impenetrable web of economic, community, and family problems. Theories of juvenile crime have focused on many of these problems, alone or in combination. Lawrence Friedman, in his 1993 book Crime and Punishment in American History, enumerates the many “wars on crime” that were lost in this country during the last three-and-a-half centuries. Mr. Friedman’s analysis underscores the conclusion that many observers have reached: There is very little that the criminal justice system can do on its own about the causes of crime because the system cannot compete with deeply rooted and complex cultural causes of crime in the United States. As a result, the system is reactive, rather than preventive.

Indeed, reacting to crime has become a political opportunity for governors and legislators, and a marketing opportunity for the mass media. Although juveniles commit a fraction of the crimes that adults commit, they provoke a disproportionate reaction. Moreover, the usual reaction to juvenile crime is to ostracize the offender rather than to understand the pattern of crime. For example, when rates of gun-involved homicides by juveniles tripled between 1984 and 1994, juvenile offenders were labeled “superpredators,” although crime rates for non-gun homicides, as well as most other offense categories, remained steady. The spike in gun homicides was mostly due to the explosion in the urban crack trade, combined with the increased severity in drug laws for adult offenders. Rather than place themselves in jeopardy of arrest, adult drug dealers recruited teenagers for the visible front lines. Thousands of young adolescents served as lookouts or runners for older cousins, siblings, and other adult “mentors” whom they emulated. Many of these offenders were fourteen- or fifteen-year-old boys who were seduced by the heightened gun use and gang activity that paralleled the crack trade, while others carried guns for self-defense (Blumstein and Rosenfeld, 1998; Canada, 1995).

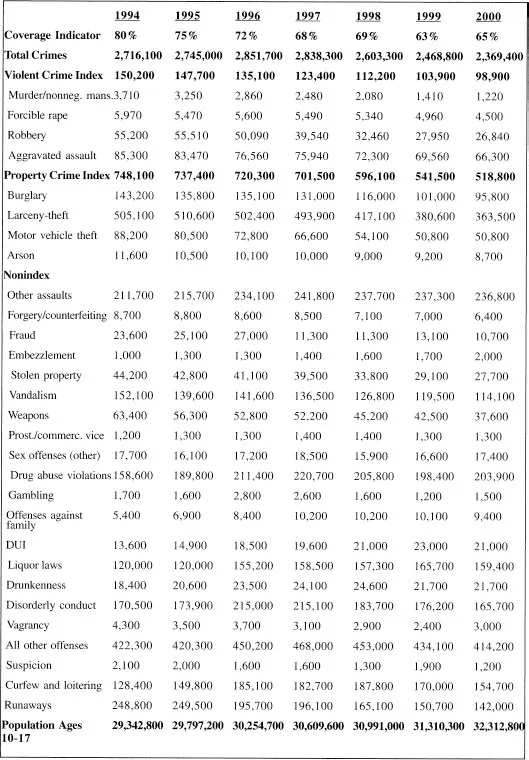

Perceptions of juvenile offenders as “superpredators” persisted well into the 1990s, even as the crime began to decelerate in 1995. By 1997, there was a three-year drop in violent youth crimes of 18 percent (see Table 1.1), due largely to community-based policing in major crime areas (Elikann, 1999). But the superpredator image was kept alive by the shooting deaths at Colorado’s Columbine High School and continued the calls for harsher punishments for juvenile offenders. The relentless media preoccupation with young “monsters” offered no hope of rehabilitation and steered attention away from important developments in juvenile justice during the last thirty years, including privatized community-based programs, a continuum of programs—many of which are highly specialized—available to fit a range of supervision and treatment needs of youths, balanced decision models to classify offenders into appropriate placements, and facility management based on performance goals.

The officials and administrators who run even the most well-regarded juvenile detention and correctional systems feel the impact of negative reactions to the juvenile justice system. The consequences of overreacting to juvenile crime are often counterproductive:

• New York State led the way for adult trials of violent juveniles in 1978 after Willie Bosket killed two laborers coming home on the subway late one night and then boasted to the media that the state could do nothing to him because he was only fourteen years old. The state of Florida followed with the most sweeping adult trial mechanism in the nation: the state’s attorney decides whether to try youths in juvenile or adult court for certain misdemeanors and all felonies, thereby bypassing the need for a waiver hearing. Many believe that the results of this law have been disastrous: Florida prosecuted over 6,000 juveniles in criminal court in 1998. State laws now permit children as young as twelve to be tried as adults in Colorado and Missouri, and as young as ten in Kansas and Vermont (OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book, 2002). Ironically, these legal directions contradict recent biological evidence about adolescent development. Daniel Weinberg, director of the Clinical Brain Disorders Laboratory at the National Institutes of Health, has studied brain development and particularly the prefrontal cortex, which inhibits impulsive behavior, anticipates the future, and associates cause and effect. Scientists insist that at age fifteen, evidence clearly demonstrates the immaturity of the prefrontal cortex (Weinberg, 2001), which is believed to be the last section of the brain to mature (McGough, 2002).

• Overcrowding the juvenile system. If there is a single factor that will ultimately destroy an effective juvenile detention or correctional system, it is the overcrowding of programs so that they become dangerous environments for youths, provoking more violent behavior and failing to provide safe opportunities for positive behavioral change. In 1991, one-third of all public detention centers, accounting for 47 percent of confined juveniles, were in facilities whose populations exceeded their reported design capacity (Parent et al., 1994). By 1995, the overcrowding problem spread to half of all public detention centers, which held nearly three-quarters of the nation’s residents (Snyder, Howard and Melissa Sickmund, Juvenile Offfenders and Victims: 1999 National Report, Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice).

Dale Parent (1994), who studied patterns of confinement of 65,000 juveniles in nearly 1,000 juvenile corrections and detention facilities throughout the United States, found that resident and staff injury rates were higher in crowded facilities, and higher juvenile-on-juvenile injury rates were associated with large dormitories. Ten percent of confined juveniles were in facilities where at least 8 percent of the residents were injured (and whose injuries were known to staff and reported) by other residents during a thirty-day time frame. One percent of juveniles were in facilities where 17 percent or more of staff were injured during that period. Injury rates for staff and residents alike were higher in facilities where living units were locked twenty-four hours a day, despite a heavy emphasis on security in such units. The percentage of juveniles convicted for violent crimes was not related to injury rates, which supports the theory that violence in facilities is environmentally induced, rather than caused solely by characteristics of the residents.

• Use of juvenile facilities to support the adult system. Dealing with the severely strained adult court system has forced backlogs and over-crowding problems onto juvenile detention facilities, where juveniles are often held pending the outcome of their adult trials, and where such youths are generally co-mingled with less serious youths who are being processed as juveniles. Data analyzed by Amnesty International in 1998 suggested that as many as 100,000 youths under age eighteen are prosecuted in criminal courts each year; roughly 180,000 of these prosecutions occur in the thirteen states with an upper juvenile court age limit of fifteen or sixteen (Young and Gainsborough, 2000).

Table 1.1

Estimated Arrests of Persons under Age 18 in the United States, 1994-2000

Estimated Arrests of Persons under Age 18 in the United States, 1994-2000

Adapted from: Snyder, H., Puzzanchera, C., Kang, W. (2002) “Easy Access to FBI Arrest Statistics 1994-2000” Online. Available: http://ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/ezaucr/

Given the environmental obstacles that youths often face, including increasingly violent subcultures and early childhood traumas caused by abuse, neglect, and exposure to violent communities, correctional officials should balance the competing concerns of protecting youths, on the one hand, with controlling youths, on the other. What is needed is a comprehensive discussion of the primary considerations that policymakers should use in striking a balance between holding youths accountable for their past behavior, and providing services and opportunities to change their environments so that future behaviors will be guided by constructive, rather than destructive, forces.

Juvenile correctional systems should be held accountable in two important ways: first, they must protect not only the public but the youths with whom they are charged; and second, they must provide social services to youths with multiple medical, psychological, educational, family, community, and legal problems. The average youth who is placed in the care of the juvenile justice system has been exposed to a combination of “risk factors” such as poverty, domestic violence, community violence, learning disabilities, single parents with serious personal problems, abuse, and neglect. In order to meet the challenges of these problems, programs for juvenile offenders must be creative, flexible, oriented towards community reintegration efforts, and accountable for decisions. As correctional organizations evolve, decision-makers become more aware of the differences among youthful offenders and the need for specialized programs and policies to fit characteristics of the offense and the offender. Yet government provision of services to youths is often disastrously neglectful.

In 2002, Florida’s social service agency was caught sleeping by investigative newspaper reporters who easily found nine of the 532 children in their care whom the agency had “lost” through poor record keeping and failure to track cases in a professional manner (Boston Globe, 2002). Most states’ social service systems allow children to simply “fall through the cracks.” In juvenile correctional systems, offenders are locked up often for the convenience of the system, not for public safety needs. And even when youths are under lock and key, programs fail to deliver needed services because of administrative inconvenience and cost, even when such services would reduce the risk of recidivism. We believe that two key trends will emerge in the twenty-first century. On the positive side, some states and counties will lead the nation by establishing performance goals, such as lowering assaults in their facilities and increasing educational standards, and they will monitor their performance by collecting data and motivating staff to make improvements. On the negative side, many states will continue to make decisions based on the political ambitions of a handful of individuals.

In considering the future of juvenile justice, we need to examine the past. In defining what has constituted “juvenile justice” up to this point, there is a chronological series of different answers. This is because, historically, there have been a number of politically ideological groups that have accepted the challenge of balancing protection with control, and have devised their own ideologically shaped solutions. The dominant views on the state’s role vis-à-vis juvenile offenders have changed from one time period to another, originating with the progressive or liberal view, which survived the longest period, from roughly the turn of the century into the 1960s; the libertarian view, which challenged the liberal view and lasted until the late 1970s; the conservative view, which emerged in the late 1970s and has persisted into the twenty-first century; and the fundamentalist view, which coexisted with the conservatives and dominated during the Reagan administration.

The history of juvenile justice reflects the diversity and competition among political interest groups, much as it exists in many other sectors of our society. A thorough analysis of juvenile justice must be able to draw insight from various perspectives on handling juvenile offenders. The lessons of history can be used to help develop an approach that is consistent with recent and foreseeable trends in communities, families, the economy, government, politics, and juvenile offenders themselves.

1.2 The Liberal View

Historically, the liberal or “progressive” view of the state as protector of juveniles shaped the early philosophy of separate treatment of juvenile offenders in juvenile courts and correctional placements. Policies to control juvenile offenders in the United States were formulated a century ago as a philosophy that is separate and distinct from “adult justice.” Structurally, there are many important and distinct characteristics of an autonomous juvenile justice system. Separate institutional facilities for juveniles were first created in 1848 (in Massachusetts), and a separate juvenile court was first founded in Cook County, Illinois in 1899. The process began with a separate juvenile court that operated under a different mandate than the adult court, with flexible intake and diversion provisions, and with different laws and vocabularies that defined the legal rights of youths. The parens patriae philosophy of the juvenile court was best articulated in the words of Judge Julian Mack in 1909, when thirty states had just established separate courts for juveniles. Mack noted that before the inception of the juvenile court, the aim of punishment for juvenile offenders was no different than punishment for adults—retribution for wrongdoing, or as a deterrence to others (Mack, 1909). Punishment was meted out in proportion to the degree of wrongdoing, rather than in a manner intended to improve the offender. Judge Mack (Mack, 1909, p. 107) described punishment that was consistent with progressive thinking:

Why is it not just and proper to treat these juvenile offenders, as we deal with the neglected children, as a wise and merciful father handles his own child whose errors are not discovered by the authorities? Why is it not the duty of the state, instead of asking merely whether a boy or girl has committed a specific offense, to find out what he is, physically, mentally, morally, and then if it learns that he is treading the path that leads to criminality, to take him in charge, not so much to punish as to reform, not to degrade but to uplift, not to crush but to develop, not to make him a criminal but a worthy citizen.

At the time of the juvenile court’s inception around the turn of the century, the court’s Progressive creators envisioned a process for handling juvenile offenders that would be informal, highly flexible, child-centered, and scientific. The Progressives’ ideas were drawn from a variety of sources that were part of larger societal changes that were taking place at that time. The American culture was changing rapidly as a result of urbanization, industrialization, immigration, and shifting roles within the family. Children were being looked at differently, as was the whole concept of childhood and family. Rather than viewing children as laborers, as many were in rural settings during the 1800s, children during the Progressive era were regarded as “corruptible innocents” who needed protection from the state. Progressive reformers sought scientific solutions to deviant behavior that identified the causes and prescribed the cures. These early rehabilitative efforts demanded discretionary decision-making so that cases could be handled on an individualized basis, with the focus on the child rather than the offense (Feld, 1987).

The rehabilitative model allowed for provision of services to juveniles that de-emphasized their offenses and highlighted their treatment needs. The benevolent intention (or guise) of the juvenile court enabled the state to broaden its definition of deviant behavior by means of the “status offense” category, which included smoking, sexuality, truancy, immorality, stubbornness, vagrancy, or living a wayward, idol, and dissolute life (Feld, 1987). Many of the children charged with status offenses were in fact homeless, parentless, or economically disadvantaged, and were placed into institutions for indeterminate periods of time on the basis of “expert” judgments about the needs of the child. One legacy of this era is that status offenders who were prosecuted in juvenile court were routinely institutionalized until the federal government intervened in 1974.

In addition to the status offense category, which applies only to minors, the creation of the juvenile court established other differences between juvenile and adult court proceedings. To protect the youth’s privacy, most sessions are closed to the public, whereas adult courts allow the public to observe, and records are generally confidential. In juvenile court, there are “hearings” rather than trials, youths are “adjudicated delinquent” rather than found guilty of a particular offense, and the disposition or sentencing options are, in theory, more reforming than are those for adults. The emphasis on reforming juveniles’ behavior requires a more detailed assessment of youths and their backgrounds than what is done for adults, and more specialized programs that are tailored to the youth’s individual needs. Juvenile offenders are placed into programs that purport to assess and respond to the special characteristics of youths. Such programs are provided or overseen by juvenile correctional agencies at the state or county level. Generally, as with adults, the least serious offenders are maintained at the county level, where they are given a disposition of probation that is supervised by court probation departments, although county correctional programs are becoming more diverse and creative in a few jurisdictions, such as Los Angeles County and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

The juvenile court has two broad options with serious offenders. Offenders charged with violent felonies can be transferred to adult court, which in some states is also called certification, bindover, or waiver, for an adult trial and sentence. Alternatively, the juvenile court has the option in most states to dispose of these cases itself, just as it has with any less serious cases, by “committing” the youth to state jurisdiction. In many states, this means that the judge directly sentences a youth to a particular institution. In a growing number of states, however, the judge has more limited control and merely sentences the youth to the state correctional agency, which then determines the placement. If the youth does indeed remain under control of juvenile corrections, as opposed to being convicted and sentenced as an adult offender, there is a presumption that rehabilitative efforts will be made. Traditional efforts include psychological treatment as well as skill-building in educational and vocational areas. More recent rehabilitative efforts for juveniles include substance abuse counseling, violence and gang prevention, AIDS education, specialized programs for juvenile sex offenders, and pre-natal health care for pregnant girls.

Although rehabilitation has been widely debated as an appropriate goal for seriously violent juvenile offenders, it is generally believed to be appropriate for the majority of non-violent juveniles due to their relative receptiveness to outside influences on their behavior, both positive as well as negative. In terms of their psychological and social development, most experts believe that adolescents are clearly different from adults, even though their offense behaviors may make them appear otherwise. The motivations for their offenses are often situational or group-induced. Commonly...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Trends in Philosophy and Politics

- 2. State Systems in Juvenile Corrections

- 3. Local Reforms in Juvenile Corrections

- 4. The Changing Role of the Juvenile Court

- 5. Balanced Decision-making in Juvenile Corrections

- 6. Developing Effective Juvenile Correctional Systems

- 7. Correcting Imbalance in Juvenile Justice

- Appendix A: Baird, Storrs, and Connelly, 1984 Juvenile Probation and Aftercare Assessment of Risk

- Appendix B: Alabama Risk Assessment Instrument and Alabama Needs Assessment Instrument

- Appendix C.1: San Bernardino

- Appendix C.2: San Bernardino

- Appendix D: North Dakota

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Balancing Juvenile Justice by Susan Guarino-Ghezzi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.