![]()

1

Prepare for Four Degrees

The UK government issued a report in summer 2008 entitled: Adapting to Climate Change in England: A Framework for Action (Defra). This is a clear statement of the perceived scope of government responsibility in this matter. In his Introduction the Secretary of State for the Environment, Hilary Benn, conceded that:

Even with concerted international action now, we are committed to continued global warming for decades to come. To avoid dangerous climate change we must work, internationally and at home, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Even so, we will have to adapt to a warmer climate in the UK with more extreme events including heat waves, storms and floods and more gradual changes, such as the pattern of the seasons.

(Defra, 2008a, pp4–5)

The report later explains the role of government which is:

Raising awareness of changing climate … will encourage people to adapt their behaviour to reduce the potential costs as well take advantage of the opportunities.

(Defra, 2008a, p20)

Finally the report concedes that ‘Governments have a role to play in making adaptation happen, starting now and providing both policy guidance and economic and institutional support to the private sector and civil society’ (Defra, 2008a, p8). In other words, ‘over to you’.

Getting down to the detail, the report’s action plan is divided into two phases. The objectives of phase 1 are:

• develop a more robust and comprehensive evidence base about the impacts and consequences of climate change in the UK;

• raise awareness of the need to take action now and help others to take action;

• measure success and take steps to ensure effective delivery;

• work across government at a national, regional and local level to embed adaptation into Government policies, programmes and systems.

In terms of the first objective, there is already enough evidence to gauge the impacts that will affect society, in particular urban society. The Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published between February and April 2007 contains data that should provide incentives to all concerned with the built environment to raise their sights to meet the extraordinary challenges that lie in wait as climate changes. However, since its publication, the IPCC report has come under some criticism.

The Defra document used the IPCC report as the framework for its adaptive strategies. The problem with the IPCC report is that the cut-off date for its evidence base was the end of 2004. Since then, there has been a considerable accumulation of scientific evidence that global warming and climate change have entered a new and more vigorous phase since 2004. This has caused scientists to dispute some of the key findings of the report. To understand why this is important to all concerned with adaptation strategies for buildings, it is worth summarizing the various divergences from the IPCC.

First, the IPCC Report has been criticized for understating projections of climate impacts, not least by Dr Chris Field co-chair of the IPCC and director of global ecology at the US Carnegie Institute. In an address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science he asserted that the IPCC report of 2007 substantially underestimated the severity of global warming over the rest of the century. ‘We now have data showing that, from 2000 to 2007, greenhouse gases increased far more rapidly than we expected, primarily because developing countries, like China and India, saw a huge upsurge in electric power generation, almost all of it based on coal’ (reported in the Guardian, 16 February 2009).

This has been endorsed by James Hansen (Hansen et al, 2007), director of the NASA Goddard Space Institute, who believes that the IPCC prediction of a maximum sea level rise by 2100 of 0.59m to ‘be dangerously conservative’. Reasons include the fact that ice loss from Greenland has tripled since 2004, making the prospect of catastrophic collapse of the ice sheet within the century a real possibility. The IPCC assumed only melting by direct solar radiation, whereas melt water is almost certainly plunging to the base of the ice through massive holes or moulins which have opened up across the ice sheet. This would help lubricate and speed up the passage of the ice sheet to the sea.

According to Dr Timothy Lenton (2007) the tipping point element with the least uncertainty regarding its irreversible melting is the Greenland ice sheet (GIS). Above a local temperature increase of 3°C, the GIS goes into mass melt and possible disappearance. As the Arctic is warming at about three times the global average, the corresponding global average is 1–2°C.

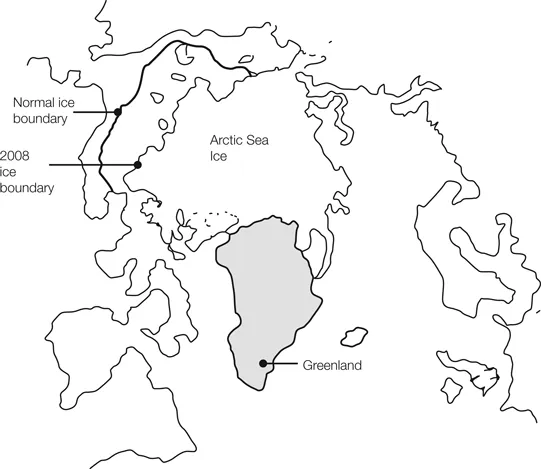

This rate of warming has resulted in the Arctic sea ice contracting more extensively in 2008 than in any previous year. A satellite image recorded on 26 August 2008 shows the extent of summer melt compared with the average melt between 1979 and 2000 (Figure 1.1).

Source: Image: Derived from the US National Snow and Ice Data Center

Figure 1.1 Extent of Arctic sea ice on 26 August 2008 compared with the average extent 1979–2000

As further evidence of impacts, 2007 has revealed the largest reduction in the thickness of winter ice since records began in the early 1990s.

Whilst the 2007 IPCC report considered that late summer Arctic ice would not completely disappear until the end of the century, the latest scientific opinion is that it could disappear in late summer as soon as three to five years hence (Guardian, 25 November 2008, p27). One consequence of this melt rate is that an increasing area of water is becoming exposed and absorbing solar radiation. According to recent research, the extra warming due to sea ice melt could extend for 1000 miles inland. This would account for most of the area subject to permafrost. The Arctic permafrost contains twice as much carbon as the entire global atmosphere (ref Geophysical Research Letters, Guardian, 25 November 2008, p27). The most alarming aspect of this finding is that the effect of melting permafrost is not considered within global climate models, so is likely to be the elephant in the room.

The latest evidence of climate change from Antarctica has come from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). It reported in 2008 that the massive Wilkins ice shelf is breaking off from the Antarctic Peninsular. The 6180 square miles of the shelf is ‘hanging by a thread’ according to Jim Elliott of the BAS. The importance of ice shelves is that they act as buttresses supporting the land-based ice. This part of the Antarctic ice sheet has the least support from ice shelves. When it breaks away completely, this will be the seventh major ice shelf in this region to collapse. In January 2009 Dr David Vaughan of the BAS visited the ice shelf ‘to see its final death throes’. He reported that ‘the ice sheet holding the shelf in place is now at its thinnest point 500m wide. This could snap off at any moment’ (Figure 1.2).

Source: Photo Jim Elliott, BAS

Figure 1.2 Wilkins ice shelf undergoing calving

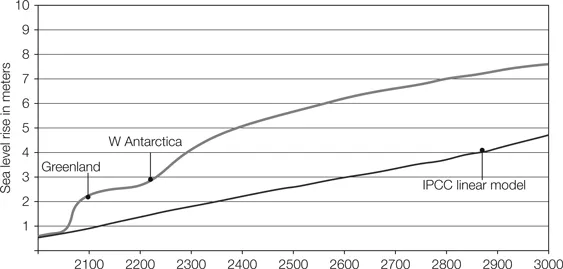

These are amongst the reasons why the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research has taken issue with the IPCC over its prediction that global warming will produce change on an incremental basis or straight line graph. Tyndall has produced an alternative graph linking temperature change to sharp and severe impacts as ice sheets melt; Figure 1.3 illustrates both scenarioa. The IPCC has since come to accept the validity of Tyndall’s scenario.

Source: Lenton et al, 2006

Figure 1.3 Potential for abrupt changes compared with linear IPCC forecast

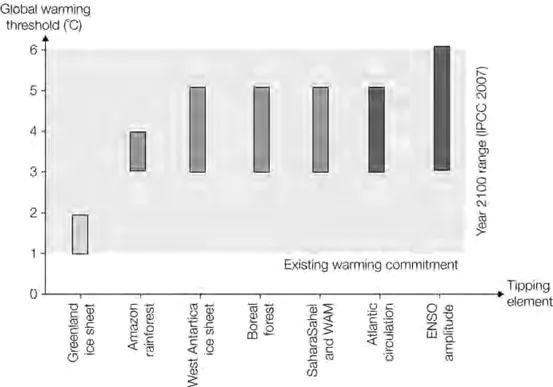

The Tyndall Centre has produced a timetable of suggested tipping points for various climate change impacts such as the melting of Greenland ice sheet which, it indicates, is underway already (Figure 1.4).

Source: Lenton, 2007

Figure 1.4 Tyndall tipping points

The idea that climate changes could be abrupt has also received endorsement from proxy evidence from the Arctic. This relates to the Younger Dryas cold period, which lasted ~1300 years and ended abruptly about 11,500 years ago. Samples from insects and plants of the period indicate that the end of this cold episode was dramatic. This has been reinforced by ice cores that show that there was an abrupt change when the temperature rose around 5°C in ~3 years. This is just one example of many sharp changes revealed in the ice core evidence and offers little room for confidence that such a change will not happen in the near future for the reasons outlined by James Hansen above.

Inevitable Warming

Hansen and colleagues (Hansen et al, 2007) suggested that the Earth climate system is about twice as sensitive to CO2 pollution than suggested in the IPCC century-long projection. A conclusion that followed is that there are already enough greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to cause 2°C of warming. If true, this means the world is committed to a level of warming that would produce ‘dangerous climate impacts’. The team has concluded that ‘if humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to the one in which civilisation developed and to which life on Earth is adapted … CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385ppm to, at most, 350ppm’. They suggest that this can only be achieved by terminating the burning of coal by 2030 and ‘aggressively’ cutting atmospheric CO2 by the planting of tropical forests and via agricultural soils.

John Holdren, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and appointed to a key post in the Obama Administration, has added weight to the argument: ‘if the current pace of change continued, a catastrophic sea level rise of 4m (13ft) this century was within the realm of possibility’ (BBC interview, August 2006).

Optimism Over Gains in Energy Efficiency

A further problem with the IPCC report has been explained by the UK Climate Impacts Programme (UKCIP) in a 2008 paper in Nature by Pielke, Wigley and Green. This paper claims that the technological challenge required to stabilize atmospheric CO2 concentrations has been underestimated by the IPCC. In particular the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) makes its calculations on the assumption that there will be much greater energy efficiency gains than is realistic, thereby understating the necessary emissions reduction target.

Pielke et al argue that the IPCC SRES scenarios are already inconsistent in the short-term (2000–2010) with the recent evolution of global energy intensity and carbon intensity. Dramatic changes in the global economy (China and India) are in stark contrast to the near-future IPCC SRES. This leads Pielke et al (2008) ‘to conclude that enormous advances in energy technology will be needed to stabilise atmospheric CO2 concentrations’.

The Amended Stern Report

A further blow to the IPCC was administered by Nicholas Stern. His UK government sponsored report, known as the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change was based on IPCC data. Since its publication in 2006, Stern has admitted that he underestimated the threat posed by climate change as posited by the IPCC. He said:

emissions are growing much faster than we thought; the absorptive capacity of the Earth is less than we’d thought; the risks of greenhouse gases are potentially much bigger than more cautious estimates; the speed of climate change seems to be faster.

(Stern, 2009, p26)

Stern concludes: ‘Last October [2007] scientists warned that global warming will be “stronger than expected and sooner than expected” after new analysis showed carbon dioxide is accumulating in the atmosphere much more quickly than expected’ (2006, p26). The Stern Review recommended that greenhouse gases should be stabilized at between 450 and 550ppm of CO2 e (equivalent). In January 2009 Stern amended the limit to 500ppm.

Scientists tend to refer solely to carbon dioxide since it is the gas that is the dominant driver of global warming and is the one that is most readily associated with human activity. It comprises around two-thirds of all greenhouse gases. On the other hand, politicians and economists often lump together all greenhouse gases and then refer to their CO2 equivalent (CO2 e).

This means that the call t...