![]()

1

Introduction

All during this century, but with especial frequency during the last thirty years, a large number of discoveries have been made in biomedical science. The area of therapeutic drug discovery and use may perhaps serve as an example of what is happening in many other areas of biomedicine. Three of what are now the eight major classes of prescribed therapeutic drugs were unknown thirty years ago. These three are the antibiotics, the antihistamines, and the psychoactive drugs. Two other major classes of drugs, the sulfas and vitamins, were introduced between World Wars I and II. Somewhat earlier in the century, barbiturates and hormones were discovered. In sum, of the eight major classes of prescribed therapeutic drugs, only narcotic drugs were known to antiquity, and today’s representatives of even this class, with the exception of morphine and codeine, are recently developed drugs.1

Accompanying this rapid progress in biomedicine, indeed a prerequisite for it, has been a very large and very rapid increase in the amount of use of human subjects in biomedical research. Although research starts in the laboratory and then proceeds to animal testing, eventually all new procedures, new techniques, new drugs have to be tested for efficacy in man. As Dr. Henry Beecher, a pioneer among those concerned for the ethics of research, has put it, man is “the final test site.” Or, in other words, “man is the animal of necessity” in this situation.

Of course, all this successful biomedical research on human subjects has enormously benefited the health and welfare of those who enjoy modern medical care anywhere in the world. However, as with probably all purposive social action, there have also been some unintended and undesired side-effects, in both the medical and the moral realms.2 Chief among the undesired moral side-effects has been the apparent failure to achieve the highest, and in many cases even adequate, standards of professional moral concern and behavior with the human subjects used in this necessary biomedical experimentation. At the center of our interest in this book are the social sources of satisfactory and unsatisfactory standards of concern and practice with human subjects.

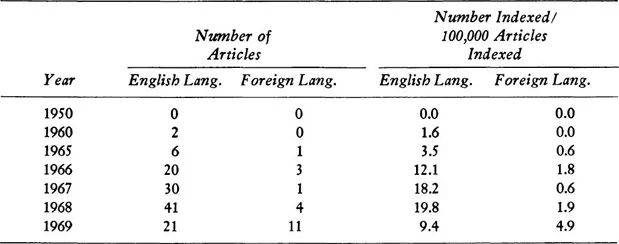

Although there has been a rather long history of attention to the problem of the possible or actual abuse of the subjects of medical innovation and medical experimentation, this attention has increased a great deal during the last ten years or so.3 First, increased attention and concern were expressed from within the biomedical research community itself.4 A little later, a number of biomedical researchers, joined by professors of law, moral philosophy, and social science, organized symposia to compose a rounded view of the problem.5 The recent increase of concern in the biomedical research community can be seen perhaps most clearly in the dramatic rise of medical journal articles devoted to facets of this problem. If we look at Index Medicus, we find an increase in both the absolute number and the proportion of articles in this area. Table 1.1 documents the results of our count of all those articles listed under the headings “Ethics, medical” and “Human Experimentation” whose titles indicate that they are indeed on the subject of the ethics of biomedical research on human subjects. It will be observed that the figures begin to get large in 1966, when the classificatory heading “Human Experimentation” first appeared in Index Medicus and when the U.S. Public Health Service first issued its requirements and guidelines to grantee institutions for safeguarding the rights and welfare of human subjects. The figures are given for both foreign-language and English-language journals and they indicate considerably greater concern in the English-language world.

Table 1.1. Number and Proportion of Articles on Human Experimentation by Year and Type of Journal

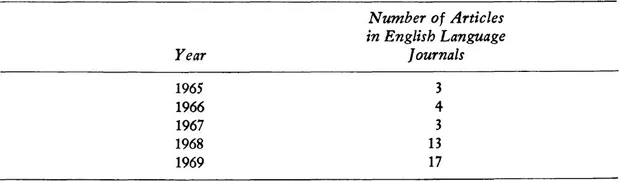

It should be noted that all articles on the subject of the ethical problems of tissue transplantation were excluded from Table 1.1. Transplantation in its early phases involves the use of experimental human subjects, of course, but it includes other ethical problems as well, for example, the ethical problem of when “life” should be ended. That is why it is indexed separately. Although tissue transplantation has been a highly publicized issue in the last few years, especially since the first heart transplants, the articles on transplantation specifically are fewer than half as many as those on experimentation more generically. In 1950 and 1960 there were no articles indexed on tissue transplantation. Table 1.2 shows the figures for 1965 to 1969.

Second, increased attention and concern have been expressed in new governmental regulations, most powerfully in those of the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration.6 Because they have mandated peer review for all biomedical research that they have supported since 1966, which includes a considerable part of all the biomedical research done in the United States as a whole and in nearly every individual biomedical research organization, the National Institutes of Health have played an especially important role in the regulation of the use of human subjects.7 The scope of governmental regulation in the biomedical and other human experimental areas has been steadily increasing. In 1971, the Food and Drug Administration, which up to that point had required only written voluntary consent from subjects, added the requirement of peer review for all clinical research. And in 1971 also, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare moved its control over the use of human subjects to a higher level than that of its subdepartment, the National Institutes of Health. The Department’s Office of Grant Administration Policy has been given authority for “establishing uniform policies for the protection of human subjects involved in research, demonstration, and other activities supported by the Department’s grants and contracts.”8 Although determination of the applicability of the policy is left to the professional judgment of the operating agencies involved, the policy is now supposed to cover all psychological, sociological, and educational research using human subjects and “certainly includes all medical research.” The Department’s new uniform policies have been stated in the Office of Grants Administration Manual, Chapter 1–40, and this statement on “Protection of Human Subjects,” now supersedes the 1969 N.I.H. regulation, “Protection of the Individual as a Research Subject.”

Table 1.2. Number of Articles Indexed on Tissue Transplantation

Third and finally, increased attention and concern have been widely and continually displayed in the mass media. This concern has been especially focused on three causes célèbres during the last ten years: the thalidomide disaster in Germany; the Southam and Mandel case in New York State in which live cancer cells were injected into geriatric patients without their informed consent; and the bitter controversy between Drs. DeBakey and Cooley of Baylor University and Houston over their own priority rights and the rights of patients in their artificial heart and heart transplant programs.9

Unfortunately, all this literature of concern, both past and present, has some important defects. Though often wise, it contains a paucity of hard and detailed facts based on representative samples of experience. Also, it lacks the understanding of some of the sources of possible ethical shortcomings in this area which can be provided by sociological analysis. Finally, because of its inadequate factual basis and its unsatisfactory analysis, the policy recommendations made in this literature have often been limited or defective. The purpose of the studies and the work carried out over a period of several years by our Research Group on Human Experimentation has been to make improvements in all these respects: to provide better facts, better analysis, and better policy recommendations.

The extensive details of our empirical findings, our sociological analysis, and our policy recommendations are presented in this book. Here, as a guide to the reader, we offer a prospect of what our book contains, a brief and synoptic outline presented to help keep the macroscopic picture in view when we come to focus on the microscopic detail that is of its essence.

Since our work represents the first attempt ever to obtain systematic empirical estimates on both expressed ethical standards and actual behavioral practices with regard to the use of human subjects in biomedical experimentation, we start with a detailed account of the design and methodology of the two studies in which we collected our data.10 The careful reader of a scientific monograph, we recognize, always looks first to see how the data were collected and measured. In this case, for example, the careful reader will want to inspect the representativeness of our samples and the validity of the instruments with which we collected data on the two key issues in this area: the issue of informed voluntary consent and the issue of the proper balance between risk and benefit in experiments done with human subjects.11 The first of our two studies, our National Survey, obtained responses to a mailed questionnaire survey from a set of 293 biomedical research institutions which our analysis shows to constitute a nationally representative sample along several important dimensions of all American institutions of this kind.12 The second study, our Intensive Two-Institution Study, obtained responses to lengthy personal interviews, using a different instrument from the first study, from the active researchers in two biomedical research institutions chosen by cluster analysis to be representative of a very large number of the institutions in our national sample.13 In one of these two institutions, University Hospital and Research Center, we obtained 331 interviews or questionnaires; at the other, Community and Teaching Hospital, 56. It is likely that, because of our high response rate (72%) and because of the method of selecting these two institutions, we do have here a set of representative responses from biomedical researchers who use human subjects.14

After describing in detail in Chapter 2 the design and methodology of our two studies, we proceed to report what we found, what the different patterns of expressed standards and self-reported behavior are with respect to the two key issues of informed consent and the risk-benefit ratio. The data, presented in Chapter 3, show two types of patterns. They show, first, that a majority of biomedical researchers using human subjects are very much aware of the importance of informed voluntary consent, that a majority express unwillingness to take undue risk when confronted with hypothetical research proposals, and that a majority do not themselves actually do studies in which the risk-benefit ratio is unfavorable for the patient-subjects. These patterns we call “strict.” But the data also show that there is a significant minority that manifests a different type of pattern, what we call “more permissive,” in each of these three respects: unawareness of the importance of, or concern with, consent; willingness to take undue risk; and actually doing studies that involve unfavorable risk-benefit ratios.

These two types of patterns, together with some other findings, are what the rest of our book seeks to explain. They are what we take as our dependent variables. Or rather, they are better seen as two “values” of each dependent variable, consisting of these ethical standards and behavior in this area of the use of human subjects for biomedical experimentation. One type of pattern is apparently the more “conforming” value of each variable, the other apparently the more “deviant” value of each variable. And both conformity and deviance with respect to each dependent variable, we feel, must be explained by the same independent variables, not by different variables.15 It is variation in the same independent variables, we try to show, that does indeed help to explain the variation we find in each dependent variable.

Our explanations, or independent variables, are of two kinds. The first looks to the conflict of equal values in socially structured situations that puts pressure on some individuals to place one value ahead of another.16 The second looks to three different types of social control processes and structures: socialization (or training) structures and processes, research collaboration groups and other informal interaction networks, and peer review committees.

Using our first kind of explanation, we assume that biomedical researchers face a conflict that we call “the dilemma of science and therapy” because they hold two equal but potentially conflicting values: to be an original discoverer in science and to be a physician who treats his patients humanely. As our data show, the majority of biomedical researchers are apparently in socially structured situations that permit them to balance these two values off against one another very nicely and thus to conform to both of them. But our data show that our more permissive or deviant researchers are in socially structured situations that put pressure on them to place the science value at least a little ahead of the humane therapy value. There are two of these sodaily structured situations that exert pressure toward deviance. One is the situation of relative but deserved failure in the structure of competition in the national and international biomedical research community. Here we have found that it is the “extreme mass producer,” the man who publishes many papers that are not admired and therefore not cited by his scientific colleagues, who is more likely to manifest the more permissive patterns of ethical standards and behavior. The second situation is the one in which there occurs relative but undeserved failure to get just treatment in the structure of rewards in the local-institutional research setting. Here we have found that a more permissive pattern with respect to the risk-benefit ratios of his human studies is followed by the man who holds a less high rank in the l...