![]()

PART ONE

THE ARCHIGRAM NETWORK

![]()

INTRODUCTION

THE IMAGE OF CHANGE

Not all [architectural] revelations have to be buildings. They could be a paragraph from Ruskin’s Stones of Venice, or Geoffrey Scott’s Architecture of Humanism, or even Asimov’s Caves of Steel. But architects being the visual, graphics-besotted creatures they are, the revelations are more likely to be engraved plates in the works of Viollet-le-Duc, or the patent application drawing that revealed the essence of Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-ino, the space-cathedral sketches of Bruno Taut or the renderings of imaginary skyscrapers by Hugh Ferris, the Fun Palace drawings of Cedric Price, the colored collages of Archigram’s Peter Cook … or Ron Herron’s Walking City drawing, a long-legged revelation stalking the surface of the globe, a truth or illusion in search of a site on which to settle and become real … But then, the work of the architect as he bends over the paper, pencil in hand, is all illusion. He produces simulacra of reality, diagrams which, by some form of sympathetic magic, are supposed to cause real buildings to happen out in the instrumental world. We all know that it is not sympathetic magic but a vast and frequently fallible industrial complex that will turn the illusory vision into real construction but, for architects, the moment of magic, the revelation of truth, is when the pencil marks the paper, and the process of making architecture begins.1

History is always written from the sedentary point of view … even when the topic is nomads. What is lacking is a Nomadology, the opposite of a history.

G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Transformation loomed large on the horizon of the postwar period, especially in those vocations directly engaged in reconstruction. With the struggle to establish modernism accomplished, the architectural profession was poised to address the changed context. But modernism itself would be ever more subject to reconsideration as the demand for flexibility of program increased, along with the sentiment for user participation in and control over the environment. For some the capacity for architecture to readily accommodate changing conditions was elevated to the primary concern. This agenda relied on the emergence of electronically driven technologies within the popular domain of consumer products and services, with the obvious time lag behind developments in the laboratory. Digital technology indicated a potential way to overcome the limits of the prevalent industrial model, and the more commercially viable it became, the more tenable the promise of compliant structures. Images of adaptive architectures that addressed the element of duration began to proliferate at the institutional fringes and even generate new forms of representation. Conjectures would range from systems design and cybernetic planning to ephemerals of all kinds, including tensile, auto-destructive and inflatable structures. The role of architecture shifted from its traditional task of designing hardware (walls, floors, masonry) to that of designing ‘software’: programs to enable diverse situations in a given space.

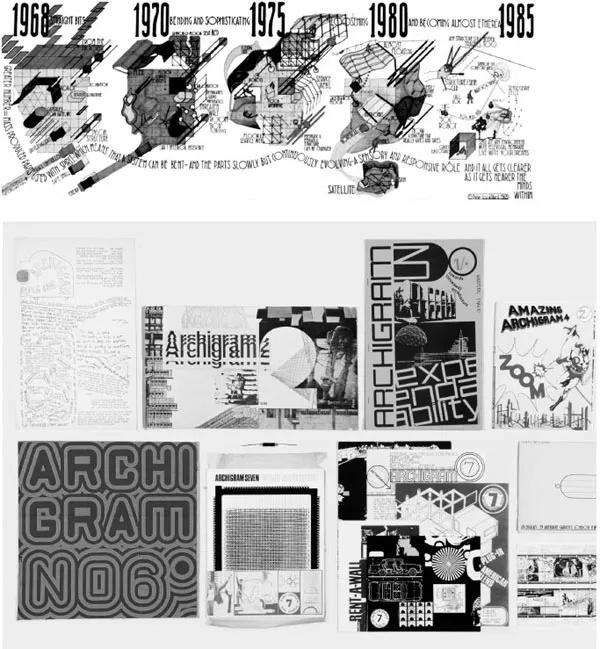

0.2

Peter Cook, ‘Metamorphosis’, 1968.

0.3

The Archigram magazines showing their relative dimensions and formats.

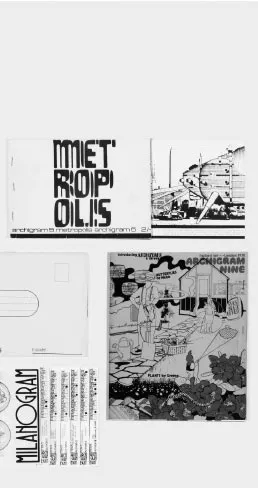

0.4

Covers of magazines, including Domus, Marcatre, Cuadernos Summa-Nueva Visión, Daily Express, Hogar Y Arquitectur and the Weekend Telegraph, featuring Archigram.

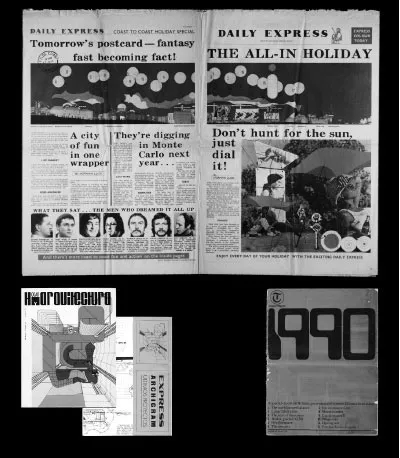

0.5

Covers for the entire run of Focus (1938–9) and of the 1948 issues of Plan, as well as the final special issue of 1951 dedicated to the Festival of Britain.

The fabrication of a visual language to express the agenda of reflexive architecture at this juncture is at the heart of this study. In particular, the focus is concentrated on Archigram, a magazine dedicated to the representation and dissemination of such environments. In the nine issues of Archigram that were published at irregular intervals from 1961 to 1970, a representational groundwork was prepared for a discipline overwhelmingly dependent on industrial processes and materials to integrate complex and indeterminate systems with architecture.2 Archigram was a publication venture that culled images and ideas from elsewhere to generate a context for the new proposals that it circulated and that would then make their way to the pages of other, more mainstream magazines at home and abroad. This project attracted attention within the architectural community through the compound use of imagery, calculated freedoms of overall layout, manipulation of common printing procedures and strategic dissemination to the project. The content self-consciously evolved from the tension between the durable and transient to proposals for megastructural networks in the first half of the decade, then on to others for self-contained skins in the second half, and finally to those for the disintegration of architectural objects into a technologically driven landscape at the end. Through the production and dissemination of imagery, the Archigram enterprise formulated an architectural vocabulary and shaped the visual output for what are now commonplace tools in the practice of design. The functioning of the publication sought to do away with the division between what was architecture and what was not – from theoretical propositions to consumer products. Even the compounded name, with its overtones of a transmission device, suggested a communications network. This attempt to conceive material objects, from cities to housing, in a world increasingly interpreted through a series of impulses was among the earliest architectural explorations of the dilemmas introduced by electronic culture.

Form

Archigram fitted the counterculture of the small magazine – the broadsheet, the samizdat, the zine – a venue considered to be a seedbed for new ideas and measure of things to come. In Britain, where there were precarious and unprofitable publications aplenty, this phase before the radical project became familiar was an easily recognized form. The period of and following World War II was a notable exception as a severe paper shortage had resulted in a 1940 governmental ban on any new publications, rendering impromptu magazines virtually non-existent.3 Once the restrictions were lifted, however, the numbers of experimental magazines surged. The architectural field in particular had experienced a lapse in the domain of ephemeral periodicals dating back to the institutionalization of modernism in the 1930s. In Britain, of the four little architectural magazines that had been started before the war, only two championed modernist solutions. The pioneer, Focus (1938-9) by students from the Architectural Association, was shut down after only four issues by the paper restrictions and other austerities. In 1943, Plan was initiated by the consortium of the Architectural Students’ Association and survived until 1951 by shifting its base of operations from school to school.4

By the 1950s, the dominance of modernism in the professional journals had been established, as the contents of the Architectural Review well illustrate, and the authors of the early alternative magazines had become the establishment. Student communities, on the other hand, grew vocal in their criticism of what was now old. There were not many opportunities for the publication of student work, though after Theo Crosby became the technical editor for Architectural Design in 1953 that magazine provided an outlet for a certain segment of the younger generation.5 Over thirty little magazines debuted from 1955 to 1970 to challenge the status quo.6 The postwar alternative reviews continued, like those that preceded them, to deviate from what was being taught in the schools and to promote a sense of professional crisis. Extremity of statement varied. From its inception in 1956, Polygon, by students from the Regent Street Polytechnic, was more successful than the Bartlett’s Outlet (1959–62) at establishing itself as radical; Manchester’s 244 (1955–62) was known for its controversial articles.7 These were all student-run magazines and, like the first two issues of Archigram, were dedicated primarily to student projects. The proliferation of such magazines was indeed so remarkable that in 1966 the critic Peter Reyner Banham (1922–88), a driving force on the alternative London scene of the fifties and sixties, declared the trend a movement.8 In an article that was key for the promotion of the Archigram project, ‘Zoom Wave Hits Architecture’, Banham identified four little magazines at the core of the trend. The oldest, Polygon, was often evoked as a seminal publication for Archigram, especially as it was where Mike Webb would publish his fourth-year studio project while attending the polytechnic, initiating a sequence of reproductions and commentary that culminated with inclusion in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960 and the initial Archigram in 1961. The newest of the lot was Clip-Kit, begun a full decade after Polygon by Peter Murray together with Geoffrey Smythe when he arrived at the Architectural Association. Another was Murray’s previous four-issue effort, Megascope (1964–6), which he had started together with Dean Sherwin while they were students at Bristol.9 The ‘reigning champion of protest mags’ was, of course, Archigram, with Amazing Archigram 4: Zoom Issue naming the trend.10 Banham’s article was centered on the Archigram case, deploying the two contemporary publications to further exemplify the influence of Archigram interests, including geodesics, plug-ins, megastructures, plastics and inflatables.

0.6

Cover of Megascope 3 (1965), the third of four issues of the student magazine edited by Peter Murray and Dean Sherwin while at Bristol.

In addition to its role as a document that lays out fundamental beliefs, the small magazine was itself a literary genre replete with a history pertaining to layout, representational techniques and typography, as well as the subversion of written and visual language. The nexus formed by the exchange of periodicals among groups of like-minded people, only compounded by the swapping of content, undermined the traditional dialectic of centrality and periphery within a profession. The result was a kind of international framework, a conceptual network, which flew in the face of the previous generation’s desire, particularly marked in Britain, to domesticate modernism to the specificities of locality, whether through social or geographical regionalism.

In tone, these magazines resembled the manifestos of the avant-gardes of the 1910s and 1920s that Banham had struggled to rehabilitate into the modernist narrative as part of his doctoral research conducted under the supervision of Nikolaus Pevsner.11 Banham was particularly interested in the alternative views of technology that had been offered by strains of modernism and throughout his career would continue to privilege work that took changing environmental or social conditions as its premise. By identifying practices that took on technologically adaptive structures, ...