![]() Part 1

Part 1

Foundations![]()

1

Geographies of empire: the imperial tradition

Learning objectives

In this chapter we will:

- Provide a working definition of empire, imperialism and colonialism.

- Explore the role of imperial expansion in shaping the content of academic geography and introduce the ideas of Halford Mackinder, Ellen Churchill Semple and Petr Kropotkin.

- Examine the theoretical frameworks emerging from the relationship between imperialism and geography.

- Trace the legacies of these theories and approaches for contemporary geography.

Introduction

In this chapter we explore how geographical thought was shaped by, and shaped, the age of European imperialism. In confronting these relationships we are exploring an extremely important issue from geography’s past. However, following the argument of geographers Cloke et al. (1991: 4), we are not engaging with imperialism and geography out of some ‘antiquarian’ concern for the discipline’s history, but rather because many of the underlying themes and discussions that emerged in this period continue to shape current geographical debates and institutional priorities. This legacy is often difficult to discern, since it has shaped research agendas and institutional

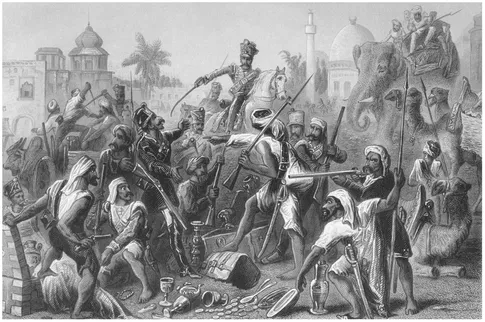

The 1847 Indian Mutiny

Source: Alamy Images/Classic Image

relationships in complex ways. These will be explored later in this chapter, but it is important to emphasise at the outset that imperialism is not a discrete phenomenon that can be confined to the distant past and is unrelated to the present. Rather, imperial institutions, practices, assumptions and imaginaries continue to shape the content of geography and the conduct of geographers.

As we shall see throughout this chapter, the 18th and 19th centuries were a time of imperial expansion, as powerful states, particularly those in Western Europe, used their military and scientific advances to claim territories in Africa, South America and Asia from their indigenous inhabitants (see photo). At the time, many explained this action as a ‘civilising mission’, bringing order to barbarous parts of the world that lacked the supposed civility of the European states. Although certain commentators, such as Harvard University’s Professor Niall Ferguson, have sought to retain this celebration of benevolent imperialism, others have drawn attention to the violence, racism and plunder on which empire thrived. The position of geography within this story is not straightforward. Certainly, geographical skills of cartography and exploration were vitally important to imperialist objectives; knowing about the world and how to traverse its surface allowed European powers to lay claim to disparate territories. But the merits of imperial expansion were the focus of sustained scholarly debate at the time. While we cannot talk of a single intellectual position among geographical scholars, there is much evidence of the ideas and theories that geographers were developing to help justify the process of imperial expansion. As geography institutionalised, it produced a range of theories that helped to explain why it was morally just that imperialism was occurring, thus entering the realm of normative theorisation (how the world should be) as opposed to simply positive theorisation (how the world is ). Theories such as ‘environmental determinism’ suggested that imperial powers were predisposed to rule over colonial territories on account of their climate and topography. Therefore, for geographers Neil Smith and Anne Godlewska (1994: 2), empire was ‘quintessentially a geographical project’.

In this chapter we explore this contention over five sections. In the first we explore what is meant by ‘imperialism’. While we predominantly examine Western European imperial conquests in this section, we must be cognisant that, just as there are many geographies, there are many imperialisms. As we have mentioned, we cannot view the age of imperialism as a discrete epoch confined to the past, but rather we can trace imperial relationships and practices in the present day. The second section explores the institutionalisation of geography over the 19th and 20th centuries. It is important to note that this process is not restricted to the emergence of geography as a scholarly discipline in universities and schools, but rather as a practical pursuit documented in museums and exhibitions, and undertaken by geographical societies across Western Europe and North America. In the third section we explore the early content of geography as it was shaped by the demands of empire, in particular drawing out the reliance on the natural sciences and the primacy of objectivity. This position, encapsulated by the theory of environmental determinism, was thoroughly discredited in later years, although its influence in geography can still be felt. But we must not assume that there was unanimity in the adoption of any single theory or school of thought. The fourth section outlines the contemporary dissent at the nature of geography, inspired in particular by the work of Russian-born geographer Petr Kropotkin. In the final section we document some of the lingering practical and theoretical implications of geography’s entanglement with empire.

Empire, imperialism and colonialism

A brief glance at the available disciplinary histories of geography gives an indication of a long association between geography and the militarised attempts to claim territory on behalf of a particular imperial project. But if we examine these accounts more closely a number of initial – and very serious – questions come to light.

First, what is meant by the discipline of geography? There are no clear boundaries to any academic discipline, since intellectual activity takes place in a diverse range of settings: universities, schools, professional societies, public associations and so on. As the geographer David Livingstone (1992) has persuasively argued, we should not attempt to locate the boundaries of the discipline of geography – this would be pointless – and instead appreciate that geography has meant different things at different times and in different places. This means that we need to understand and explore geography in context and understand that what counts as geographical inquiry may mean different things to different people. In addition, the discipline of geography has always been characterised by debate and disagreement, so it is impossible to suggest that it displays a single political or intellectual perspective. It happens that much of the institutionalisation of geography as an academic discipline took place in the latter part of the 19th century, which coincided with a period of European imperial expansion. But this should not be taken as evidence of an obvious link between geography and empire; rather, it should lead us to question the nature of this relationship and explore the range of different perspectives on imperialism voiced within the geographical discipline.

The second question that immediately comes to the foreground when reading existing accounts of the foundation of geography in the age of empire is, what is meant by terms such as imperialism, colonialism and empire? These terms are explored throughout the chapter but, as an initial comment, we should say that we cannot understand these as simple descriptors, since there were many different practices of imperialism and colonialism that differed greatly in their form and substance. Just as we need to be careful not to assume a singular definition of geography, we must be similarly attentive to accounts of imperialism and colonialism that reduce these to simple characterisations. Geographers such as Livingstone, Mike Heffernan, James Sidaway and Klaus Dodds have provided rich accounts of imperial practices in a range of different places that illustrate the shared traits but also the considerable divergences between these processes.

The third question that comes to mind is to what extent was geography alone as a discipline that is inextricably linked to the age of European imperialism? This is a crucial question, since some accounts of the relationship between geography and empire present this as an occurrence unique to this discipline. Instead, we can trace similar processes in the institutionalisation of disciplines such as anthropology, biology and medicine. As we will see, the common thread between these endeavours is a desire to utilise the analytical strength and disciplinary prestige afforded by advances in scientific practices and theories. Processes of imperial expansion necessarily drew on these same scientific practices of measurement and calculation, and thus connections may be made between these disciplines and imperialism. But we need to be careful in our unproblematic presentation of science as a benevolent form of rationality desired by many different academic disciplines. Often scientific ideas were transformed or truncated in their adoption by different disciplines and therefore their meaning was changed. As we will see, one of the key examples of this troubled adoption is Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. The geographer David Stoddart (1966) has provided a detailed account of the dangers of piecemeal adoption of Darwin’s ideas, where certain facets of his theory were ignored and others accentuated.

Defining terms

Empire, imperialism and colonialism are terms that are used to describe how people and territory are ruled. As we have discussed, definitions of these terms are necessarily of limited use, as it is in practice that we see specific differences. But as a starting point, it is important that we grasp the basic differences implied by these terms.

Imperialism is derived from the Latin word imperium, which roughly translates as power or ability to command. Therefore imperialism relates to the practice of enacting power over a particular group of people or territory. In conventional usage an empire is created through the successful deployment of imperial power. An empire can therefore be defined as an unequal territorial relationship between states often based on economic exploitation. This definition is somewhat problematic in the cases of ancient empires, such as the Roman Empire, where individual states may not have been discernable, but the economic system was still clearly structured around the extraction of wealth, or tribute, from peripheral areas back to the imperial centre in Rome.

In contrast to the idea of unequal imperial relationship, the Berkeley geographer Michael Watts describes colonialism as the ‘establishment and maintenance of rule, for an extended period of time, by a sovereign power over a subordinate and alien people that is separate from the ruling power’ (2000: 93). Thus, while imperialism focuses on an unequal relationship between states, colonialism draws our attention to the physical settlement of territory for the material or military advantage of a colonial sovereign power. As these definitions would suggest, we cannot divorce the exercise of colonial or imperial power from the expansion of the capitalist system and the emergence of a global division of labour. Therefore we would draw attention to three aspects of empire:

- The establishment and maintenance of rule by a sovereign power over a range of separate territories.

- There is a fundamental economic imperative underscoring these imperial or colonial practices.

- We can trace relations of exploitation from a discernible imperial centre towards a colonial periphery.

In order to understand the emergence of geography as an academic discipline and its entanglement with colonial practices, we need to identify some general historical points. In identifying such a historical narrative it is easy to rely on generalisations of large and complex systems of rule, for example to identify overriding characteristics of empires that covered large tracts of the Earth’s surface for several hundred years. In short: we need to remember that imperialism and colonialism have always been diverse and dynamic practices of rule, that are best confronted and understood through empirical examples.

Portuguese and Spanish empires

Let us take the example of European imperialism from the 15th century onwards to explore the central tenets of colonial expansion. Although preceded by Portuguese colonial exploration, we could isolate the voyages of Christopher Columbus between 1492 and 1504 and Vasco de Gama in 1498 as starting points of the era of European colonial expansion. Columbus was originally from Genoa (in present-day Italy) although he was largely funded by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. His voyages across the Atlantic to the Caribbean, Central America and the coast of South America ensured personal enrichment and paved the way for Spanish colonial expansion. At this early stage, geographical and navigational knowledge was vital, although not always well developed. For example, Columbus famously never accepted that he had landed on a ‘new’ continent for European explorers; he remained certain that he had sailed to the eastern coast of Asia. Vasco de Gama similarly assisted Portugal in its colonial ambitions, serving as the first European to round the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and sail to India. These early explorations allowed Spain and Portugal to establish extensive colonial possessions. From the 15th to the 16th centuries, Portugal earned great wealth through the spice trade between Asia and Europe. At a similar time, Spain enjoyed a ‘golden era’ as its conquistadores (conquerors) decimated the Inca, Maya and Aztec populations in Central and South America. These acts of violence established access to lucrative reserves of silver and gold across their fledgling colonies, while the creation of sugar plantations in the Caribbean provided further revenue streams. In addition, both the Portuguese and Spanish empires were sustained through the trade and exploitation of slave labour.

At a straightforward level these examples illustrate how geographical knowledge, and particularly navigational skills of cartography, combined with military might to help European powers project their power and economically exploit distant territories. But in the example of Portugal the geographers James Sidaway and Marcus Power (2005) have pointed to a more complex picture that underpinned processes of imperial expansion. In a line of argument that we will see repeated in later parts of the chapter, these scholars suggest that the effects of imperial expansion should not simply be traced in terms of militarism and economic exploitation. They examine how processes of imperialism have fostered forms of cultural transformation in Portugal that are still felt in the present day, arguing that imperial experiences are central to the country’s culture:

This is a state whose ‘national anthem’ begins with the words ‘herois do mar, nobre povi’ (heroes of the sea, noble people), whose flag features at its center the navigational sphere, and whose coins and banknotes (before they were subsumbed into the euro) featured maps of southern Africa and portraits of explorers.

(Sidaway and Power, 2005: 528)

Consequently the authors argue that the imperial experience is central to Portuguese understandings of national identity, in particular centring on Portugal as the metropolitan centre of an expansive empire. The authors are making an important geographical point here. They are suggesting that rather than seeing imperialism as a process of territorial expansion (literally the amount of land ruled by one state) it is, in fact, a process of identity formation. The process of imperial expansion shifts how people think and act about themselves and others.

British Empire

The combination of geography, militarism and exploitation exhibited in the Portuguese and Spanish examples was repeated on a greater scale in the case of the British Empire. Initially established in the Caribbean and North America in the 17th century, the roots of the British Empire can be found in England’s superior naval power and geographical knowledge. The initial colonies established on the coastal fringes of present-day America and the Caribbean led to the establishment of significant trade flows in sugar, tobacco, cotton and rice as well as greater numbers in the slave trade. But the empire did not remain static; the colonies in the present-day United States of America were lost after the War of Independence from 1775 to 1782 and Britain outlawed the use of slave labour in 1807. But perhaps the most significant shift occurred as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom over the course of the 18th and 19th century. The profound economic and social changes that took place over this period transformed the pace and scope of British colonial expansion. The rise of new mechanised industries, driven by steam power, acted as a catalyst to emergent circuits of global capital, structured around a need for new markets, new access to raw materials and new opportunities to invest profit ...