![]()

A BRIEF HISTORY OF NOH

Kan'ami and Zeami to the Present Day

Noh theatre as it is experienced today, has a lineage which is directly linked to Kiyotsugu Kan'ami (1332–1386) and his son Motokiyu Zeami (1363–1443). Both were Buddhists and deeply religious. The plays and the theatre form they created, contained much in the way of symbols and imagery, and could be directly linked to Shinto principles.

Their work also revealed a powerful link with the natural and supernatural. All the masked characters represented ghosts which were both ordinary and demonic, real and imagined.

What were the influences which seemed to crystalise into this refined, highly stylised dramatic form, in the hands of Kan'ami and Zeami at this particular time in Japanese history, and what was the essential ingredient which was to allow it to remain almost unaltered in its form of unbroken presentation for the ensuing six hundred years?

Like the emergence of the genius of Shakespeare at the end of a period of medieval experiment by many writers, the Sarugaku-Noh as it was called - a form of masked dance drama which also included in its programme a set of comic anecdotes, written and ‘rehearsed’ by Kan'ami -‘emerged’, and seemed to captivate and engage the sustained patronage of the shogunate of the period.

Where had it come from?

The natural environment often provokes active engagement in corporate worship, the content of which links the basic ingredients of fear and respect by those who wish to survive in harmony with the elements and the landscape. Certainly a form of ritual celebration, central to most dramas, could be traced to the festivals surrounding the seasons, the planting and harvesting of essential crops.

These celebrations and rituals would be held in special places and would be central to the cyclic order of the universe as experienced in the clearly defined seasonal changes. They would bring together the community, and would be prepared for and ‘performed’ with an appropriate sense of occasion.

There were also forms of worship at holy places in which corporate communion would take place at regular intervals, and from which ritual dances, rites, and pantomimes called Kagura evolved. Strictly speaking Kagura means God music, though it became more generally understood to be Shinto music and the rites associated with it.

There was also a strong influence from the differing cultures of China and Asia in the Nara and Heian periods of the seventh century. Dancing and music forms such as Bugaku and Gigaku, and acrobatic and mime narratives called Dengaku and Sangaku were introduced and popularised at court. These ‘entertainments’ brought with them ornate and beautifully fashioned costumes and masks.

As the centuries evolved and there was a fusion of what was native and what was imported, both the Shinto and Buddhist religions encouraged the presentation of their philosophy and faith, through a new dramatic narrative form presented by an assortment of troupes of performers who had become ‘attached’ to their shrines and temples. In a way, a parallel can be made during the same period with the more accessible medieval Miracle Cycles and Mystery plays which were establishing themselves in Britain.

By the time Kan'ami and his professional ‘family’ troupe of players had established their art and sustained a livelihood, narrative elements in the Sarugaku had developed and shifted the emphasis of the form of presentation in performance, and the Sarugaku-Noh had arrived.

In 1374 the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, whilst attending a performance of Kan'ami and his troupe, at the Imakumano Shrine in Kyoto, decided there and then that the new form of Sarugaku-Noh which he was seeing for the first time was so enchanting that he instantly adopted the troupe that performed it and became its patron.

Over the next few years, he took a special interest in fostering the intellectual, artistic and social development of Kan'ami's son Zeami, exposing him to the learned attentions of poets and philosophers. Such a comprehensive education was unusual because of the traditionally lowly social status of the performer. But it is clear that this period in Zeami's development was fundamental in its influence upon the refined form of Noh which was to emerge when he eventually became the young master of the Kanze school on the death of his father in 1386.

The evidence which accompanies this short history of the origins of Noh is open to much conjecture. The facts are few and to some extent are not unlike the kind of developments which were being experienced elsewhere in Europe.

However, the most influential and crucial documents which were compiled and completed towards the end of his life, and was left for future generations of Noh actors to study and follow, were the Treatises of Zeami: twenty-one major statements on the art of Japanese Noh theatre. In my view, this is one of the most important and yet most neglected documents on actor-training that has ever been written.

Before I address my attention to this vital document, in the next chapter, I wish to offer a detailed description of the physical shape and structure of the performance and preparation areas of the Noh stage, of how this space is filled with an assortment of performers, and finally offer a detailed examination of the composition of a Noh play in all its constituent parts.

The Origins of the Noh Stage

The Noh acting space is simply defined as being an approximate nineteen foot square which is physically ‘bridged’ by an entrance corridor for the main performers, linking the ‘dressing’ space to the up stage right corner of the acting square. The audience surrounds two, and sometimes three, sides of this square, thus creating a ‘thrust’ arena.

The design of this simple space evolved over many years, but had become more or less fixed, as described above, by the latter half of the sixteenth century. It is a straightforward matter to trace its shape and scale to the ‘gathering’ space in which celebratory dances and narratives were conducted outdoors, in the natural landscape, within convenient proximity to the community dwellings.

Performers must be seen and heard. The exterior acoustic defines its own limitations for the performer. Gatherings outside seem to have a more embracing sense of contact when the performing space is enclosed within the defined outline of buildings or a garden.

Without exception, all the Noh theatre spaces which have been constructed in Japan possess this sense of intimacy. Audiences are measured in hundreds rather than thousands. Even the National Noh Theatre in Tokyo, despite its magnificent wooden stage and auditorium, is a performing space, where the actor seems always in close proximity to all the members of the audience.

In the early outdoor performances, the travelling troupes carried only the minimum of properties and staging. Essentially fit-up and temporary, it could be set in any reasonable landscape, and could be a system of stakes, ropes and tentage which would simply define the area for preparation, performance, and audience.

It is not difficult to assume that Masters such as Kan'ami, once he had secured reasonable financial support, would invest in such basic needs as a decent portable flooring which could reproduce in its size and surface the training and ‘rehearsal’ space in which the plays were prepared. The evolution and fixing of this performing space would naturally follow from these practical requirements. It is no surprise to actors who are continually performing that the performing area ‘evolves’ naturally once the basic shape and requirement of the drama has been defined.

As the troupes became more and more popular and associated with their patrons and therefore with the social and political development of Japan, so the programmes and place of performance seemed to require a more systemised style of presentation.

Noh stages became fixed in the sense that their basic design was constructed as a roofed building separated from the area (or building) where the audience was seated, and linked to a preparing and dressing space by a corridor. The stage and corridor was raised above a ‘garden’ of gravel or sand which also filled the space between the ‘auditorium’ and the stage.

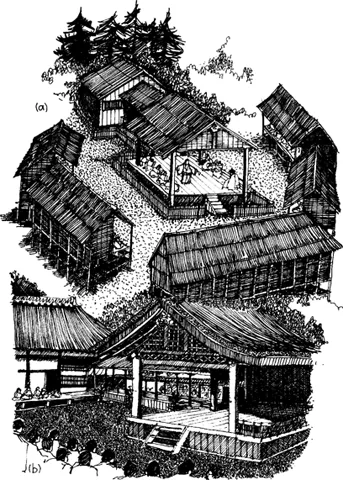

2. Origins of the Noh stage:

(a) A conjectural Noh stage at the time of Zeami

(b) Northern Noh stage at the Nishi Honganji, Kyoto (1591)

The earliest example of such a stage which is still in existence is the northern stage at the Nishi Honganji in Kyoto and dates from 1591 (see ill. 2(b)). Its design serves as the model upon which all subsequent Noh stages have been built, with few modifications.

The other links with its outdoor ancestry is embodied in the stylised painted pine and bamboo designs on the upstage walls, and by the three miniature pine trees which descend in height and perspective from the upstage right pillar, dividing equally the length of the bridge.

Occasionally paper pendants adorn the space between the pillars reminding us of the deep association with the Shintoism and the shrines where Noh is still performed as a religious ritual.

The greatest feature of the Noh stage is its simplicity. Even when it is set within the ‘high-tech’ concrete walls of a towering Tokyo cuboid, the scale and design of this simple performing space seems to carry with it its own, magical, uncluttered focus of pure beauty. As you enter, and join in the communion with the rest of the audience, you are aware of the wooden beams and thatch and open joints and carvings of craftsmen. Here is an immediate and continuing link with the constructing art of a previous age.

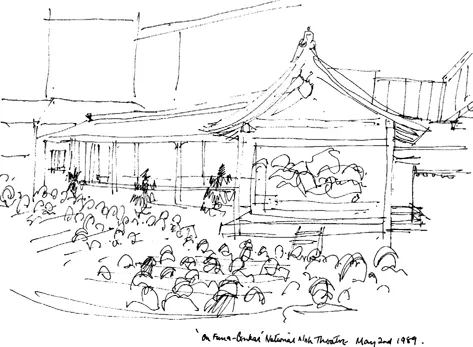

3. On Funa-Benkai, National Noh Theatre, Tokyo

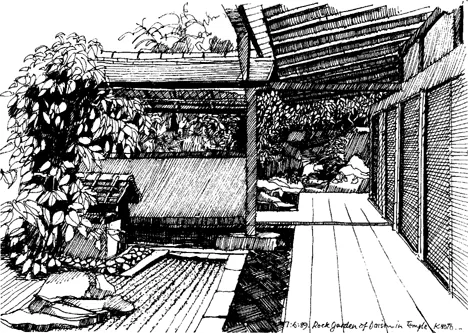

4. The rock garden of the Daisen-in Temple, Kyoto

From the first invocations of the flute to the concluding exit of the musicians, this illusion of time suspended in the distant past is maintained. You remain, as you began, with the stage.

It is transformed in performance in time and place according to the words of the narrative. It is gilded only with the strokes of shapes and sounds and properties which allow the minimal interference with its basic worldliness. This stage is ‘everywhere’ in location and time.

Its definition is altered only by the skills of the performers, and is never tainted by over-elaborate sets and accompanying technological distortions of sound and light. A still, quiet, general light reproduces that of daylight for both performer and audience. The Noh theatre is a place for deep contemplation, and everything in its design supports and respects that philosophy.

The Noh Stage and its Occupants

The stage is made...