![]()

1

A tale of two compacts

Introduction

On 19 September 2016, the United Nations convened its first-ever Global Summit on Refugees and Migrants. The 193 member states adopted a far-reaching statement – the New York Declaration on Refugees and Migrants – and set in motion processes that culminated in December 2018 with the adoption of a new Global Compact on Refugees and a new Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. At one level, this book is the story of how these two global compacts came to be and how they were negotiated. But this book is also the story of what this three-year process tells us about the evolution of still-separate global regimes on refugees and migration and about global governance more generally. At an even broader level, the international community’s collective response to the international movement of people has profound implications for the future of multilateralism and collective action.

The Summit and the processes of developing the compacts occurred at a particular moment and in a particular political climate. At the time the Summit was called, hundreds of thousands of Syrians and other migrants and asylum-seekers had begun walking toward Europe; as governments constructed walls and instituted onerous entry requirements at land borders, many of the migrants and asylum-seekers took to flimsy boats and set off across the Mediterranean. This followed the 2014 arrival of tens of thousands of Central American children on the US border; at the same time frontline developing states which had hosted millions of refugees, sometimes for decades, were demanding more international support. When the decision was made to convene the Summit – in December 2015 – there seemed to be a collective yearning for coordinated, multilateral action to deal with the thorny issues of migration and refugee movements. After all, in 2015, the UN had managed to adopt three major multilateral agreements: the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) (UN 2015a), the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN 2015b) and the Paris Agreement on climate change (UNFCCC 2015). All three of these agreements were nonbinding, aspirational in nature and relied on voluntary commitments for their success, but all three dealt with important global issues where international cooperation was necessary. In spite of weaknesses in global governance – particularly the failure of multilateral systems to prevent and resolve conflicts – the UN agreements in 2015 seemed to set the stage for collective action on migration and refugee movements.

But some six weeks after UN member states unanimously adopted the New York Declaration at the Summit on Refugees and Migrants and six weeks after the Obama administration organized a Leaders’ Summit on Refugees, Donald Trump was elected president of the US on a virulently anti-immigration platform. Almost overnight, the US, historically the acknowledged world leader on refugee and humanitarian issues, crossed over to the other side and became a champion of restrictionist policies.

Over the course of the following two years, the very foundations of the international liberal world order were shaken. Alliances which had been seen as fundamental to security were brushed aside. Populism and nationalism surged in Europe and North America. Walls went up in Europe – where free movement of people was the very cornerstone of European integration. European countries struggled with the implications of the UK’s decision in June 2016 to withdraw from the European Union (Brexit) – a decision fueled in large measure by a desire to limit immigration. Protectionism surged. Common commitments and values to the international system seemed to be replaced by transactional politics. Multilateral, collective diplomacy was out and unilateral decision-making on the basis of America First policies was in. Europe fumbled and cracked as right-wing movements gained enough political force to shape national politics throughout the continent – from Denmark to Hungary, from Poland to Sweden.

In this turbulent time, the issues of refugees and migration were thrust into the spotlight. Traditionally, migration, refugees and humanitarian issues have been marginal to the great issues of war and peace. Suddenly, they were catapulted into the center ring of the global diplomatic stage.

The story of how the world is dealing with the movement of people in the 21st century is not just about technical details regarding the negotiations of specific paragraphs in the Compacts. Instead, it is a story with important implications for the future of multilateralism writ large. The international refugee system, developed in the immediate post–World War II period, was based on a very different set of power relations and model of the world order than the current period. To its credit, the refugee system proved to be elastic and, over seven decades, has responded effectively to very different situations than those intended by its founders. But in 2015, the arrival of more than one million refugees and migrants on European borders pushed the system to a breaking point. World leaders agreed that it was time to look again at the response mechanisms for refugee arrivals.

The international migration system is a very different animal than the international refugee regime; rather than being grounded in a specific convention devised by Western powers during the Cold War, the global migration regime is rooted in national sovereignty and only loosely grounded in international law, despite the near-universal ratification of international human rights instruments. Since World War II, hundreds of millions of migrants have traveled safely and legally to work in other countries and contributed to global prosperity. However, over the years there have been periods of anti-immigrant sentiment, often directed at illegal or irregular immigrants. This xenophobia again reared its ugly head around 2015, particularly due to the fact that migrants were often taking the same routes – and using the same smugglers – as refugees. Increasingly, the media portrayed both refugees and migrants as a threat to security, identity and culture.

The acknowledged weakness of the system to withstand the pressures of the movement of a million people in 2015 is a harbinger of other changes to come; the limits of other global institutions developed in the same post–World War II era now show signs of wear. The central premise of this book is that the global compacts on refugees and migration, negotiated in 2018, are both a symptom and a cause of fundamental changes in the global order that has prevailed since World War II.

A word on definitions and data

Almost every discussion of refugees and migrants begins with either definitions or numbers – and usually both. Definitions matter (see Box 1.1 later in the chapter). The international regimes on migration and refugees are very distinct and are rooted in differences in definition between refugees and migrants. Refugees are forced to flee – because of persecution for one of five reasons spelled out in the 1951 Convention – and in broader understanding because of generalized conflict, war and wide-scale violations of human rights. Because they do not enjoy the protection of their governments and because world leaders agreed back in 1951 that it was in the collective interests of the world that they be protected and assisted, refugees were to be allowed to enter the territories of the 1951 Refugee Convention signatory states and not to be returned to countries where their lives would be threatened. Migrants, on the other hand, are presumed to be moving voluntarily in search of better opportunities, jobs or to join family members – although it is clear that many migrants also feel compelled to leave their countries. Unlike the obligations of signatories to the 1951 Refugee Convention, states have no international obligations to allow migrants to enter their territories. While there is a universally recognized right to seek asylum and to leave one’s country, there is no recognized right to migrate. Moreover, state sovereignty has no limits when it comes to accepting migrants – though international human rights law mandates that their basic human rights, whether regular or irregular, be upheld. Most states have their own policies for allowing migrants to enter their countries, usually on the basis of employment or family ties. And yet there is still confusion about the differences between refugees and migrants. For example, reporting on the decision to adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, The Guardian’s headline read, “UN States Agree Historical Global Deal to Manage Refugee Crisis” (McVeigh 2018).

Numbers and trends

Migration trends

People have used migration to adapt to their environments for centuries. Approximately 150,000 years ago, humans emerged in East Africa and, after some 50,000 years, they reached East Asia and Australia. Afterward, they also settled throughout northern Europe, the Americas and the Pacific Islands (Oppenheimer 2003). Today, many continue to use migration to adapt to the resources and risks embedded in the communities where they live. In some communities with long legacies of out-migration, it has become a rite of passage for many young adults (Kandel & Massey 2002; Monsutti 2007).

Most data about the numbers of international migrants are based on censuses that contain information about the birthplace of foreigners and natives. Censuses taken at fixed times, such as every ten years, reveal the numbers of migrants in a specific place and at a specific time, although these estimates are complex because they reflect deaths as well as migrant exits and entrances during that fixed period of time (Rogers 1990).

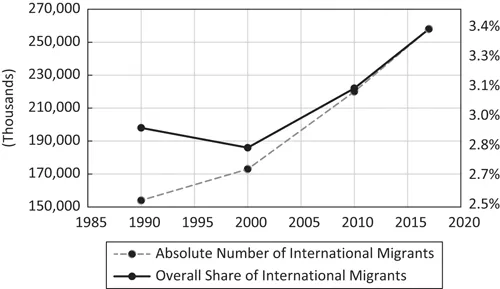

Based on stock estimates – that is, people living outside their country of birth for at least one year – the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) (2017) reported that, in 2017, there were 258 million international migrants, constituting 3.4 percent of the world’s population. Comparing these figures to those for 1990 and 2000, Figure 1.1 documents increases since 1990, when there were 154 million international migrants. By 2000, there were 174.9 million international migrants, representing slightly more than 2.8 percent of the world’s population (UN DESA 2017, 1).

FIGURE 1.1 Recent trends in international migration: 1990–2017.

There are several important patterns and trends in international migration. First, most international migrants reside in a small set of countries and/or regions (UN DESA 2017). More than 60 percent of international migrants live in just two world regions: Asia (80M) and Europe (78M), and most live in a small number of countries. In 2017, more than half lived in just 10 countries/areas, and two-thirds lived in 20 countries/areas. In addition, the share of international migrants living in high-income countries is much higher than that for low-to-middle income countries (64 vs. 36 percent). Second, in many wealthy countries worldwide, migration has been a key driver of population growth. For example, in the US, estimates suggest immigration will drive population growth for the next 50 years (López et al. 2018). Third, although the median age of all international migrants has grown from 38 to 39.2 years between 2000 and 2017, in some regions such as Asia and Latin America the median age of migrants has declined by approximately 3 years (UN DESA 2017). Similarly, although most international migrant populations are gender balanced, ranging between 47 and 53 percent female (Donato & Gabaccia 2015), in some regions, men outnumber women as international migrants and, in others, women outnumber men.

Refugee trends

The number of refugees and asylum-seekers is estimated at 25.9 million, or 10.1 percent of the world’s 258 million international migrants (UNHCR 2018). Like migrants, around half of the world’s refugees and international migrants are women and around half are children. Women face particular risks of violence before, during and after their movement. Children and youth, whether traveling alone or with their families, are at risk during their journeys, at borders and as refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Bhabha & Dottridge 2017).

Among the refugee population, 19.9 million come under the mandate of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) with 5.4 million Palestinian refugees under the mandate ...