This is a test

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Sue Jennings and her three children spent two years on a fieldwork expedition to the Senoi Temiar people of Malaysia: Theatre, Ritual and Transformation is a fascinating account of that experience. She describes how the Temiar regularly perform seances which are enacted through dreams, dance, music and drama, and explains that they see the seance as playing a valuable preventative role in people's lives, as well as being a medium of healing and cure. Her account brings together the insights of drama, therapy and theatre with those of social anthropology to provide an invaluable theoretical framework for understanding theatre and ritual and their links with healing.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Theatre, Ritual and Transformation by Sue Jennings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Setting the scene

We can learn from experience – from enactment and performance of the culturally transmitted experience of others – peoples of the Heath as well as the Book.

(Turner 1982:19)

Life is theatrelike – Theatre is lifelike.

(Wilshire 1982:ix)

Life is not a rehearsal.

(Julie Walters in She ’ll be Wearing Pink Pyjamas)

INTRODUCTION

The Senoi Temiars of Malaysia regularly perform rituals for the maintenance of health as well as the curing of physical, social and supernatural manifestations of ill-health. Their preventive and curative seances are stimulated by, and enacted through, dreams, dance, music, drama and trance media, imbued with complementary themes of the erotic and ascetic, and an underlying aesthetic sense of creative performance. I wish to explore the context of these performances in relation to the Temiar belief system and to consider the complementary roles of shaman and midwives who are engaged in the healing process. In order to understand the Temiar perceptions, it is necessary to describe their beliefs and concepts concerning the human body and the space surrounding the body, both actual and symbolic; as well as the ritually enforced boundaries of what may enter or be kept outside of bodies and space. We shall discover that these phenomena, encapsulated in the ritual dramas enacted at seances, present the Temiar world in symbolic performance. Dominant themes that recur throughout the Temiar beliefs and cosmology, tiger, thunder and blood, are epic metaphors which, through their polysemic properties are constant reminders of Temiar identity. This identity is reinforced both individually and collectively. Ritual and ritual dramas transform undifferentiated experiences into an understandable world within which the Temiars are able to maintain their sense of self and other, particularly in relation to well-being and ill-health.

In addition to relevant anthropological material, I draw upon theories from play, drama and theatre, dramatherapy and psychotherapy. Indeed it is through this study that I have achieved a greater understanding of the fundamental nature of the dramatic act and its significance in human development and creativity as well as in therapeutic intervention. I have had to expand my anthropological frame of reference in order to understand the complexity of the Temiar data and its processes. Additionally, I shall draw out the significance of the role of women in Temiar society, not as a subject in itself out of context, but in order to achieve a balance within the whole.

There is virtually no information on the play of Temiar children, which I feel is necessary to more fully understand the Temiar world view. Before describing the Temiars in any detail, it is necessary to develop the themes of play, drama and theatre in relation to ritual.

Play

The appearance of symbolism … is the crucial point in all interpretations of ludic function. Why is it that play becomes symbolic, instead of continuing to be mere sensory motor exercise or intellectual experiment, and why should the enjoyment of movement, or activity for the fun of activity, which constitutes a kind of practical make-believe, be completed at a given moment by imaginative make-believe?

(Piaget 1962:162)

Play is not ‘ordinary’ or ‘real’ life. It is rather a stepping out of ‘real’ life into a temporary sphere of activity with a disposition all of its own. Every child knows perfectly well that he is ‘only pretending’ or that it was ‘only for fun’.

(Huizinga 1949:8)

Play is a developmental activity through which human beings explore and discover their identity in relation to others through multiple media including their own bodies, projective media and a variety of role-play. Play encourages symbolic thought and action and stimulates the emergence of metaphoric expression. In play we learn to create as well as to set limits; we learn about freedom as well as its boundaries. The human body is the primary means of learning, and experiences in play gradually develop in relation to surrounding space. However, play occurs in a symbolic space, a special space set apart that is imbued with significance for the duration of the play activity: ‘It is “played out” within certain limits of time and place. It contains its own course and meaning’ (ibid.:9).

It is through playing that a child begins to separate out ‘dramatic reality’ and ‘everyday reality’ which is essential for maturation.

The infant is born with creative potential and the capacity to symbolize: indeed, it is the very capacity of human beings to pretend or make-believe which enables them to survive. We cannot envisage a life within which we could not imagine how things are – how they were, or how they might be. The creative imagination is the most important attribute that we can foster in children, and it is the basis of creative playfulness.

(Jennings 1993:20)

The roots of play and expressive behaviour emerge in infants after a few days. Before an infant can walk it can move and make sounds rhythmically, make marks (albeit with food or faeces) and respond mimetically to the facial expression of another. All the experience of sound, movement, mark-making and mimicry are embodied and experienced sensorially in small infants. These are activities which may develop later into music, dance, art and drama. However, in infancy the experiences are undifferentiated, reinforced and heightened by physical handling: touching, stroking and bouncing activity between infant and caring adults. Cultural expectations are transmitted through these experiences, especially those concerning gender and cleanliness. The body is a primary means of learning.

About the time of walking the infant is able to project outside of its own body into more concrete media; differentiation between self and other is projected into a ‘transitional object’ or beloved toy (Winnicott 1974). The ‘transitional object’ takes on a representative role and enables the infant to tolerate absence of the carer for increasing periods of time. He or she is therefore able to symbolise: here/not here and me/not me. Psychologists emphasise that the transitional object is a carer substitute and I contend that other possibilities about its function are neglected. It is my own view that it marks a major stage of dramatic development; for example, the object is usually given a name, is talked to, and answers; it is used to conceal and reveal; for example, when a blanket is put over its head and removed again; it takes on a role, as well as enabling the infant to become that role. It therefore creates a symbolic presence of significant absence as well as enabling projective and role development through objectification and personification (Jennings 1986). Infants today generalise into more extended play through multiple media, and various roles and personalities are tried out. I would describe the play during the first ten months as mimetic; the child embodies the voices, gestures and behaviours of significant others, and, as Mead (1934:225) points out, learns more about itself by becoming the other. By ten months the child is the ‘actor’ and needs an audience (Courtney 1980:45).

I refer to the three stages outlined above as embodiment, projection and role (Jennings 1990:93), which do not develop in a unilinear way but have a cumulative effect and are carried forward into more complex play activity. I maintain that this progression is essential for dramatic play to develop in children. How it develops and whether it will move into what we choose to call artistic activity is culturally determined. Contemporary psychologists have suggested that the two brain hemispheres control complementary areas of activity: there seems to be a dominance in our society of left brain activity (logic, reasoning, words) over right brain activity (intuition, creativity, metaphor). Education at all levels places greater value on science and technology than on the arts. I therefore suggest that we are left brain dominated. The possibilities that are inherent in early play are not developed equally. It is noticeable that left brain problem solving and computerised play are stimulated earlier and earlier.

I maintain that dramatic playing is essential for healthy survival as the growing child separates out everyday reality from dramatic reality. Failure to achieve this can result in everyday life becoming like a Greek drama.

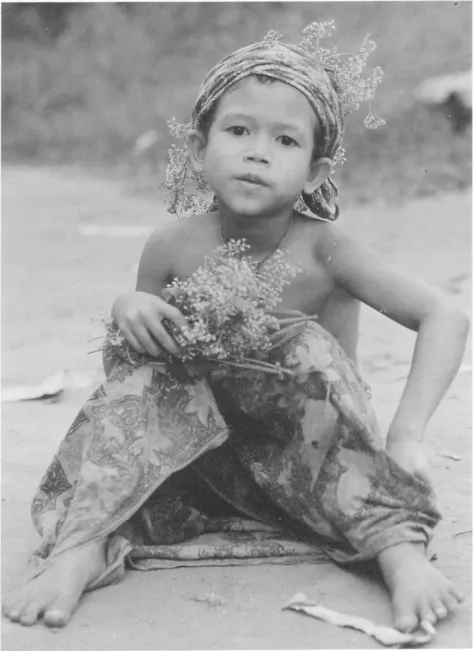

How does this relate to the Temiars? One could claim that Winnicott’s theory will only hold up for western infants, especially since cross-cultural studies of transitional objects and projective play have not, to my knowledge, been carried out. However, the Temiars manage their early childhood development rather differently. There is a strong sense of embodiment of experience in the first year, especially since infants are regularly massaged, stroked and caressed. They are also held tightly but with tension, their ears are covered during thunder storms, and older people chant ‘fear, fear’. Weaning does not take place at a particular time; infants are breast-fed up to 3 or 4 years of age, not only by their mothers but by other breasts that may be available. They are also carried constantly until they can walk. Once they are walking, they become the baby in children’s family play and are carried around on the backs of 5- and 6-year-olds (Plate 2, page 6). Thus the projective stage (without the mediation of a ‘transitional’ object) emerges in play while breast-feeding is still continuing. Infants gradually take on more roles in family play and differentiate several ‘others’. This, I suggest, enables the child to make a more radical transition by the age of 8 when he or she starts to sleep with the peer group rather than close to the parents. Temiar children of 8 and 9 years group together and choose which house they want to sleep in on any particular night. The filial bond is being replaced by the sibling bond as the child’s autonomy continues to grow (this was a very difficult thing for me to adjust to when at the age of 7 Hal went to other houses to sleep with his peer group).

Plate 1 Playing at seance (i)

Plate 2 Playing at families

Children are also encouraged to talk about their dreams, and dreams are seen as a valuable and creative activity. The concept of play carries over into Temiar adult life with the activities of music, dance, enactment and trance in what are termed play-seances. Children will already have been enacting seances in their own play in or under the house or in a corner of the village (Plate 1, page 5).

I do not wish to elaborate here on the many theories of play and development (Jennings 1993:20), but I do want to draw attention to the importance of play in the ontological development of human beings; although satisfactory play experiences are crucial for the development of gross and fine motor skills, identity, relationships, imagination and conceptual thought, I want to stress the importance of play in relation to what we call the arts and dramatic play and drama in particular. Play itself is the activity that is at the root of artistic expression, and for the Temiars it starts with the dream. I now want to move on to discuss drama and theatre, both as metaphors for everyday life, and as creative performances embedded in human societies.

Drama and theatre

Drama and theatre have been used as metaphors to talk about life for hundreds of years. The quotation from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, ‘All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players’, is perhaps the most well-used example. Dramatism and dramaturgy are terms used to describe the study of social dramas in which we are all engaged. Harre suggests that the alternative to scientism is a combination of dramatism and praxiology:

[T]hat we live out our lives in accordance with scenarios centred round the local conventions for the representation of character and the restrictions imposed upon the physical means by which we realise practical projects deriving from the nature of the physical and biological world.

(1981:79)

Goffman has contributed to our understanding of social drama through his detailed studies of interaction and impression management. As he says when discussing performances in public life:

The larger the number of matters and the larger the number of acting parts which fall within the domain of the role or the relationship, the more likelihood, it would seem, for points of secrecy to exist.

(1969:71)

Goffman develops his theory of front-stage and back-stage performance of people’s social roles. Until comparatively recently, research and writing on social drama had been polarised from drama and theatre itself, with the claim that drama is merely a metaphor for describing human behaviour.

Furthermore, we can see within western education that drama and theatre themselves are separated; drama is seen as creative action based on improvisation, and theatre as a finished product or performance (see in particular Slade 1954; Heathcote 1971). Theatre itself has become marginalised from the experience of the majority of people and is often viewed as an elitist activity catering for a minority. Theatres have closed down for lack of subsidy or turned into television studios or bingo halls. Any school curriculum demonstrates its value by the central position that is occupied by science and technology and the low priority given to the arts in general and drama in particular (a recent applicant for funding was told not to mention the word drama but to talk about social learning through social skills!).

Anthropologists have also fallen into the trap of polarising drama and theatre. Victor Turner was criticised for using the word drama when talking about social action, by both Firth and Gluckman. Drama was considered too loaded a word (Turner 1982:91). Many anthropologists make a clear distinction between ritual and theatrical performance; others have suggested that theatre grew out of ritual. However, one cannot separate theatre from ritual by saying that the former is performance. Performance enters all domains of human existence in both secular and religious fields; the ‘dramas of everyday life’ as well as the ‘dramas set apart’, i.e. theatre and ritual. I shall explore ritual in more detail later in this chapter.

The word theatre derives from the Greek theatron which literally means a place for seeing. However, it is also linked to the word theoria meaning spectacle. It becomes more pertinent to my argument when we consider that spectacle also meant ‘to speculate and to theorise’; therefore in the ancient Greek meaning, it was necessary to have something visible, something seen in order to theorise and understand. This was achieved through the spectacle of the drama (from the Greek dron, meaning action). However, Plato vilified the person and nature of the actor and said that the art of acting could be morally damaging. If a person can represent a bad character on stage then it follows that he cannot be a good person. Plato maintains that tragedy will excite in the audience emotions that should be curbed:

Then is it really right, to admire when we see him on the stage, a man we ourselves be ashamed to resemble?

Is it reasonable to feel enjoyment and admiration rather than disgust?

(The Republic)

For Plato, the creation of images is the lowest level of mental functioning and art is an avoidance of reality. He said that any actor who could act any part well should be honoured highly and escorted speedily out of the city!

Wilshire claims that in ancient Greek civilisation, reality and appearance are essentially linked. He says: ‘An occurrence was denoted by a word from which our “phenomenon” derives directly, and it means literally “that which shows itself”. Further “phenomenon” is related to the Greek word for light (phos)’ (1982:33).

He suggests that the perceptual sense of things is rendered by theatre, while analysis and synthesis of the embedded concepts come from philosophy. But he warns against developing a mentalistic view of consciousness: ‘We will assume that the recognition is between consciousness rather than between bodies that are occasionally conscious’ (ibid.: 166, my emphasis), and ‘Most significant is the way a person’s body-image is connected with his direct experience of others’ bodies as they are immediately lived by them’ (ibid.: 188).

Wilshire goes on to develop his theory that the essence of theatre is that the audience is mimetical...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Setting the scene

- 2 Introducing the Temiars

- 3 Boundaries and transformations

- 4 Temiar body: Control and invasion

- 5 Temiar space: Order and disorder

- 6 Dreams, souls and trance

- 7 Women and blood

- 8 Temiar healers: Shaman and midwives

- 9 Healing performances: Dance-dramas of prevention and cure

- 10 The epic metaphor: The paradox of healing

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index