- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Joseph II

About this book

Joseph II (1741--90) -- son and eventual successor of Maria Theresa -- has conventionally been seen in the context of the "Enlightened Despot'' reformers. Today's turmoil in his former territories invites a rather different perspective, however, as Joseph grapples with the familiar and intractable problems of creating a viable unitary state out of his multi-national empire in Central Europe. Professor Blanning's brilliant short study, based on extensive archival research, offers a history of the Habsburg monarchy in the eighteenth century, as well as a revaluation of the emperor's complex personality and his ill-fated reform programme.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Joseph II and the Habsburg Inheritance

. . .

Assets

'Everything in politics is very simple — but even the simplest thing is very difficult'. This paraphrase of Clausewitz's dictum on war would have carried conviction on the lips of Joseph II. On 1 January 1781, only a month after the death of his mother (on 29 November 1780), he wrote to the Grand Duke and Duchess of Russia that his elevation to sole rule had brought crushing burdens which kept him at his desk from early in the morning until late at night. He lamented that in such une vaste et grande machine as the Habsburg Monarchy, good could be achieved only slowly and with great difficulty, while the slightest mistake did harm very quickly. With rueful humour, he added that when a German bureaucrat, trying to speak French, mispronounced his place of work as a bourreau [hangman] when meaning bureau [office], he spoke truer than he knew.1 After less than ten years of torment at the hands of the hangman, Joseph died (on 20 February 1790), exhausted, prematurely aged, embittered and deeply disappointed by his apparently total failure. As his own despairing epitaph put it: 'Here lies a prince whose intentions were pure, but who had the misfortune to see all his plans collapse'.2

When assessing the validity of this crushing selt-indictment, it is difficult but important to avoid the 'teleological trap'. By that is meant the knowledge that the Habsburg Monarchy lurched from one crisis to another after Joseph's death (1797, 1801, 1805, 1809, 1848, 1859, 1866 and so on) and was finally expunged from the map of Europe altogether by the peace settlement which followed the First World War. Once the final destination - the telos-is known, all previous events can be seen as rites of passage on a journey as preordained as is every human's route from birth to death. Oscar Jaszi's influential work The dissolution of the Hahsburg Monarchy begins with the very foundation of the dynasty's fortunes in the late thirteenth century, while those of A.J.P. Taylor and C.A. Macartney on the same theme take Joseph II as their point of departure.3 Whatever the theoretical preconceptions of the author, this is history with a sense of inevitability built-in. It necessarily stresses problems and failures at the expense of assets and achievements. Not only does it distort the eventual collapse by exaggerating its inevitability, it also leads to a misunderstanding of the nature of the past, especially by the application of anachronistic concepts taken from a later period.

Although it is clearly impossible to forget what came afterwards, it is not necessary to write the history of joseph II as if it were one episode in the pre-history of the Fall of the house of Habsburg,4 An attempt, at least, can be made to follow Ranke's dictum that 'every age stands in direct relationship to God', or in other words that every age has its own identity and validity and should be studied on its own terms and for its own sake. With specific reference to the Habsburg Monarchy during the life of joseph II (1741-1790), this requires a recognition of opportunities that were missed as well as traps that were blundered into.

First and foremost, it requires the recognition that the European states-system in the mid-eighteenth century was exceptionally fluid. In 1700 the largest country in Europe in terms of area (with the exception of Russia) had been PolandLithuania, the greatest empire had been ruled by Spain, while the richest, most populous and most powerful state had been France. By the time Joseph II died, a truncated Poland-Lithuania was sliding towards total elimination from the map, the Spanish empire in Europe had been partitioned and its hegemony overseas had been wrested by the British, while France was immobilised by revolution. Other casualties included the Swedish empire in the Baltic, conquered by Peter the Great of Russia in the Great Northern War (1700-21) and the possessions of the Ottoman Turks around the Black Sea, conquered by Catherine the Great of Russia in the two wars of 1768-74 and 1787-92. In the course of the eighteenth century, four empires (the Spanish, the Swedish, the Polish and the French) collapsed, a fifth (the Holy Roman Empire) began to totter terminally and a sixth (the Ottoman) was pushed back to the European periphery.

As the frontiers of eastern and southern Europe waxed and waned, opportunity knocked with the same insistence that danger threatened. Countries with the will and ability to adapt could move from obscurity to hegemony in just a few generations. In 1657 Louis XIV sent a letter to Tsar Michael of all the Russias, unaware that he had been dead for twelve years;5 in 1735 a Russian army marched to the Rhine; in 1759 a Russian army raided Berlin; and in 1779 Russia became a guarantor of the peace of Teschen and thus a guarantor of the status quo in Central Europe. Poland, by contrast, lost about a third of her territory and population in the first partition of 1772, about a half of what remained in the second partition of 1793 and all the rest in the third partition of 1795. She was to remain conspicuously absent from the European map for 124 years.

The Habsburgs were well-placed to take advantage of this territorial upheaval. Prudent and lucky marriages dating back to three all-important unions with the heiresses of Burgundy (1477), Castile and Aragon (1496) and Hungary and Bohemia (1515) had created an empire which stretched across the breadth and much of the length of Europe, not to mention the New World. Despite the division into separate Spanish and Austrian branches in 1521-2 and the extinction of the former in 1700, resulting in the cession of Spain and the overseas possessions to a Bourbon, there was plenty left by the time Joseph II was born in 1741 to form a collection of territories impressive in both its quantity and its quality. In the Austrian Netherlands (covering much of present-day Belgium and Luxemburg) and the duchy of Milan there were towns, high population-density and wealth; in parts of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Lower Austria there were rural industries; in Styria, the Bohemian massif and the mountains of Upper Hungary, there were deposits of iron ore; on the great plains of Hungary, bisected by the navigable Danube, there was at least the potential to make the entire Monarchy self-sufficient in agricultural produce; on the southern and eastern periphery of the Monarchy there was a great deal of empty space awaiting settlement and development.

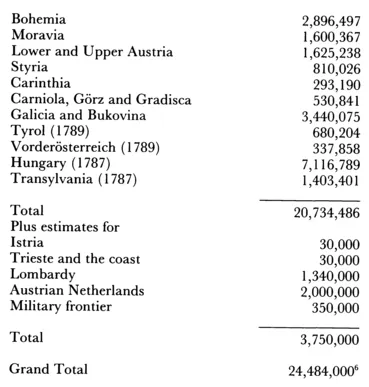

In the great-power currency of the day, what mattered most was population. Although difficult to credit, there was a widespread belief that the population of the world had been declining steadily since classical times, so there was no perception of the problems which could arise from demographic pressure. By this yardstick, the Habsburg Monarchy was well-placed. With its total population of about 25,000,000, it was rapidly overhauling France (28,000,000 in 1789) and not so very far behind the Russian empire. The figures yielded by the conscription of 1791 revealed the following provincial distribution:

Moreover, the core of the Monarchy, centred on the Danube valley, was ringed by a cordon of natural obstacles — the Bohemian forest, the Moravian Heights, the Carpathian mountains, the Transylvanian Alps, the Dinaric Alps and the Alps proper — which invaders always found very difficult to penetrate. As no less a person than Frederick the Great ruefully conceded in 1744 after his failed invasion:

It must be allowed that it is more difficult to make war in Bohemia than in any other country. This kingdom is surrounded by a chain of mountains, which render invasion and retreat alike dangerous.7

Of all the Habsburg Monarchy's numerous and varied enemies, only Napoleon ever succeeded in taking Vienna.

Relatively secure behind this natural rampart, the Habsburgs were well placed to influence, if not dominate, events in the Balkans, eastern, central and southern Europe. In addition, the scraps of territory in south-western Germany (known collectively as Vorderdsterreich or 'anterior Austria') and the substantial possessions in the Low Countries brought western Europe too within their orbit. Only the Baltic lands clearly lay beyond their grasp, although even here a Habsburg presence was maintained by virtue of the fact that northern Germany as far east as the Leba (not far from Danzig) formed part of the Holy Roman Empire. Indeed, the imperial nexus gave the Habsburg emperor influence, both formal and informal, right across German-speaking Central Europe.

This relationship between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Holy Roman Empire was as important as it is confusing. As the map on page 220 shows, the two overlapped but were by no means identical. Founded by Charlemagne's coronation as emperor by Leo III in Rome on Christmas Day 800, the Empire had developed over the centuries into a decentralised amalgam of princes great and small, both secular and ecclesiastical, together with fifty-odd self-governing municipalities, and all presided over by an elective emperor. By the mid-eighteenth century, there were nine electors: three ecclesiastical (the archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier), and six secular (the king of Bohemia and the electors of the Palatinate, Saxony, Bavaria, Brandenburg and Hanover).

From 1452 onwards these electors had always chosen a Habsburg as emperor, so there was a natural tendency to assume that the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy merged into each other. Their essential separability, however, was demonstrated in 1740 when the emperor Charles VI died without a male heir. The possessions he had ruled by virtue of being head of the house of Habsburg — the Habsburg Monarchy — passed to his daughter Maria Theresa, who ruled them using the most senior of the many titles she had inherited — 'King of Hungary'. However, under the Salic law which governed the Holy Roman Empire, as a woman she could not have been elected empress, even if the electors had been inclined to do so. Attempts to secure the title for her husband —Francis Stephen — failed, the electors preferring one of their own number, Charles Albert of Bavaria, whom they elected as emperor Charles VII in 1742. It was not until 1745, following Charles' brief and unhappy reign, that Francis Stephen could be elected as emperor Francis I and the connection between Holy Roman Empire and Habsburg Monarchy restored.

It is important to realise, however, that the connection was still only personal — it was based on the essentially contingent fact that the Holy Roman Emperor, Francis I, and the ruler of the Habsburg Monarchy, Maria Theresa, were married to each other. Their son Joseph was elected 'King of the Romans' in 1764, which in effect gave him the automatic right to succeed his father as emperor on the latter's death. When that happened the following year, Joseph became the emperor Joseph II, but the government of the Habsburg Monarchy remained firmly in the hands of his mother. He did become 'coregent' of the Monarchy, but this was due solely to the generosity (or cunning) of Maria Theresa. As we shall see in a later chapter,8 the relationship between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Queen of Hungary — between son and mother — was not always amicable. It was not until Maria Theresa's death in 1780 that Holy Roman Emperor and head of the house of Habsburg (or, more correctly, the house of Lorraine or perhaps LorraineHabsburg) were one and the same person once aeain.

In other words, between 1740 and 1780 there was a separation between Holy Roman Empire and Habsburg Monarchy, although it was only between 1740 and 1745 that the separation was total. It will be argued later that this separation, caused simply by the inability of the last of the Habsburgs Charles VI — to sire a legitimate male heir, had a profound and mainly detrimental effect, not only on the Habsburg Monarchy but also on Germany and even Europe as a whole.9 Here what needs to be stressed is the influence which the emperor was able to exercise and the benefits this brought to the Habsburg Monarchy.

As with so much else relating to the politics of eighteenthcentury Europe, it mainly concerns religion. When the religious upheavals of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries finally abated and both Catholics and Protestants were obliged to accept that they could not achieve total victory, about twothirds of the population of the Holy Roman Empire had become Protestant.10 This denominational balance was not reflected, however, in the political structure of the Empire. On the contrary, there the ratio was almost exactly reversed. This was due mainly to the survival of most of the ecclesiastical principalities — eighty-odd archbishoprics, bishoprics, monasteries, even nunneries, which all enjoyed princely status, or in other words were full self-governing members of the Empire, were not subject to any other prince and were represented in the imperial parliament (Reichstas).11

These prelates naturally gravitated towards the Habsburg emperor on that most reliable of political principles: 'my enemy's enemy is my friend'. The enemy in question was the group of larger secular princes, most of whom were Prot...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Dedication

- Chapter 1 Joseph II and the Habsburg Inheritance

- Chapter 2 Joseph II, Maria Theresa and Josephism

- Chapter 3 Joseph II and the Enlightened State

- Chapter 4 Joseph II and the Privileged Orders

- Chapter 5 Joseph II and the Great Powers

- Chapter 6 Joseph II and the Crisis of the Habsburg Monarchy

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

- Chronology

- Map

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Joseph II by T C W Blanning,T.C.W. Blanning in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.