This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Did the Thatcher years and their aftermath constitute a revolution or a restoration in education. Do they represent a departure from, or a reinforcement of tradition? Contemporary Debates in Education is a thought-provoking volume which reviews the reforms of the eighties and early nineties, then follow this with an examination of the long-standing issues in education over the last century in order to relate current reforms and changes to their broader historical background, so that those with a general or professional interest in education can better understand the process in which they are involved.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Contemporary Debates in Education by Ron Brooks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Contemporary Issues in Education

CHAPTER 1

A decade and more of debate

Teachers in post and students in training face a dilemma. The reforms of recent years, which have left no sector of education untouched, have made and will continue to make demands on the time and energies of teachers in training and in post which are far greater than at any other period in the history of the profession; yet, more than ever before, they need time to reflect on the nature of the changes and reforms in order to meet effectively the challenges which they pose. But time is in short supply whether it be on the overcrowded timetable of teacher training courses or in the increasingly busy schedules of the classroom. Such apparently simple questions as ‘What are the aims of the national curriculum?’, ‘Does the concept of a state curriculum stand outside British tradition?’ or ‘Why has technical education been given such a high priority in recent years and do the values upon which this priority depend conflict with the traditional values of British education?’ require careful thought in order to arrive at an informed response. Satisfactory answers to such questions can only be given by reference to historical developments. This book seeks to help students, teachers and the many lay people now involved in running the nation’s schools to understand the historical nature of change by turning history on its head. This approach is used in order to maximise understanding in the short time available.

TURNING HISTORY ON ITS HEAD

The relevance of the history of education to an understanding of contemporary issues in education has sometimes been obscured by its treatment on training courses. On initial training courses it has taken the form of a historical chronology of developments in education from early times to the present day. This approach, from Bell to Baker or from Montessori to MacGregor in less than twenty lectures, is thankfully in decline. It was often too brief and sketchy to provide any satisfactory or immediate insights into the historical nature of present-day issues in education. At in-service meetings it tends to be replaced by a second approach, that usually subsumed under the programme heading ‘historical background’ or ‘historical introduction’. This tends to marginalise the value of the history of education. It treats it akin to a booster rocket which can be discarded once the lecture is lifted into scintillating orbit. It ignores the vital point that today’s issues in education are not simply historical in their background; they are historical in their very nature. To change the metaphor, it is not akin to a plug and socket, something which is detachable. The following chapters seek to avoid the chronological gallop and plug-and-socket history by adopting a third approach.

The third approach is to turn history on its head, to consider first not the most distant but the most recent history in order to identify within their historical context those issues which today confront the student, teacher, school governor, educational administrator or the many other groups involved in education. The term ‘educationist’ covers a much wider group of people than have been involved in education hitherto. Having identified these issues within their recent history, the book then traces their more distant but equally relevant historical development on an issue-by-issue basis rather than by a bland historical chronology. By doing this it aims to show that present-day concerns are historical in the sense that it is their history that gives them their meaning. Brief documentary extracts will be provided to point up key aspects of educational history and to provide a succinct basis for discussion of particular issues. By turning history on its head, by considering more recent historical developments first, it is hoped that discussion will be encouraged from the outset, with later chapters dealing with earlier developments this century progressively widening the scope and deepening the content of such discussion.

THE EDUCATIONAL AGENDA SINCE 1976

Where do we begin the identification of current issues within their recent historical context? For one main reason, 1976 makes a convenient starting point. That was the year in which the Labour Prime Minister, James Callaghan, made his Ruskin College speech – a sort of educational state-of-the-nation speech – which launched what his Education Secretary, Shirley Williams, termed the ‘Great Debate’ of February and March the following year. Rarely do prime ministers make public pronouncements about education, and thus his speech is of importance for several reasons. Firstly, it signifies the growing interest of central government in the various sectors of education. Coming as it did two years after the reorganisation of local government which seemed to leave education more firmly in the grip of the 104 enlarged local education authorities than ever before, it marked a stage in the assertion by central government of its stake in the nation’s education system. This stage was followed by the rapid extension of the powers of central government in the 1980s. Secondly, it marks a stage in the transition of Britain from the expansionist, swinging sixties, through the sober seventies to the austere eighties. The sober tones of the Ruskin College speech marked the realisation that the public purse was not bottomless and that education should give value for money in the sense of contributing to what politicians believed was the national good. This was interpreted by Callaghan, his Labour Government and successive Conservative governments of the 1980s largely in economic terms. Thirdly, the Prime Minister’s homely rhetoric, eminently quotable, spanned most of the items on the educational agenda. It crystallises much contemporary political opinion on a broad range of issues from primary to university education. There is, however, a fourth reason of particular relevance to the approach of this book: it provides a good basis not simply for identifying current issues in education but also for outlining some of the views on these issues. In his speech Callaghan acknowledged his indebtedness to one of the leading Labour educationists of the twentieth century, R. H. Tawney, from whom he claimed to have ‘derived a great deal of (his) thinking years ago in the early days … when he was one of the originators of the Labour Party programme on education’.1 In fact, Tawney had very different views from Callaghan on most educational issues. Educated at Rugby and Balliol College, Oxford, he defended a traditional system of liberal values and practices in the years to 1950, so very different from that advocated by Callaghan and his immediate advisers in 1976.2 Thus we have a bifocal perspective on the issues. The Ruskin College speech provides the structure for the present chapter and the framework for discussion in later chapters. Tawney provides the historical peg on which we can later hang these issues.

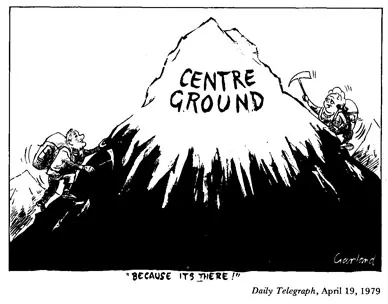

Fig. 1.1 ‘Because it’s there!’

CENTRAL GOVERNMENT AND THE CURRICULUM

It is not my intention to become enmeshed in such problems as whether there should be a basic curriculum with universal standards – although I am inclined to think that there should be. (Callaghan, 1976)

Callaghan’s Ruskin College speech testifies to the growing interest of central government in the school curriculum. While he was cautious not to make any explicit reference to government direction of the curriculum, it was difficult to believe – given his diagnosis of the problems confronting education and the general drift of his thinking about how they should be resolved – that he was not envisaging some kind of increased central government involvement. In the opening paragraph of his much-heralded speech, he argued that educational matters were of public concern, and deplored those who had advised him ‘to keep off the grass’. His homely horticultural imagery was not too far removed from that of Sir David Eccles, the Conservative Minister of Education in 1960, who argued that the school curriculum should no longer be regarded as a ‘secret garden’.3 Callaghan was insistent that there should be no ‘holy cows’ in education, that there should be no areas that ‘profane hands’ were not ‘allowed to touch’. He did not say precisely whose ‘profane hands’ these should be, but the purpose of the ‘Great Debate’ to which his speech was a prelude was intended, in part at least, to justify increased government involvement in the running of education. He had to be mindful as a Labour prime minister not to antagonise the teachers’ unions, especially the NUT, but was anxious to do something about the fact that government had little direct leverage on the curriculum.

Tawney belonged to a different age and had fought long and hard to remove central government’s stranglehold on the curriculum in the years to 1926.4 His fear was that government had, and could in the future, abuse its power over the curriculum to make it serve the interests of those other than pupils, such as industry or political ideologies. As a member of the Board of Education’s Consultative Committee, and close friend of such educationists as Percy Nunn, he had come to respect the judgement of professionals and argued that, within the general framework of a balanced curriculum, the teachers were the people best able to decide its content. In Secondary Education for All (1922) and during the Consultative Committee’s enquiry into adolescent education (1924–26) he argued for variety of curricular provision to meet the needs of the different abilities and interest of pupils. He thus saw the role of the state largely in terms of making provisions for raising the school leaving age and providing free secondary education for all to ensure that all pupils were able to benefit from a teacher–controlled curriculum up to the age of 16. The task of central government was to make such provision and to prod laggardly local education authorities into making sure that local resources were adequate and well directed.

This kind of thinking was very much in retreat half a century later. While Shirley Williams, Callaghan’s Education Secretary, was noted for her willingness to enter into prolonged discussions about educational issues with teachers and other interested parties, the Conservative governments of the 1980s reduced the length of consultation to effect legislation in a manner which was totally alien to that in which earlier legislation, especially the 1944 Education Act, had been effected. The more forthright ministerial style of Conservative education secretaries was characteristic of most Ministers in the Thatcher era. Shortly after coming to power in 1979 the Conservative Government published a document on the curriculum, signalling its intention to strengthen the centralist grip over this area. While ‘A Framework for the School Curriculum’ was intended as a discussion document it indicated clearly the avenues along which discussion should proceed, advocating...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- The Effective Teacher Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Editor's Preface

- Author's Preface

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Part One Contemporary Issues in Education

- Part Two Generic Issues in Education

- Bibliography

- Index