![]()

Part One

The Tudor Crown, the English Nation, and the Heritage of Anglo-Norman Expansionism 1550-1603

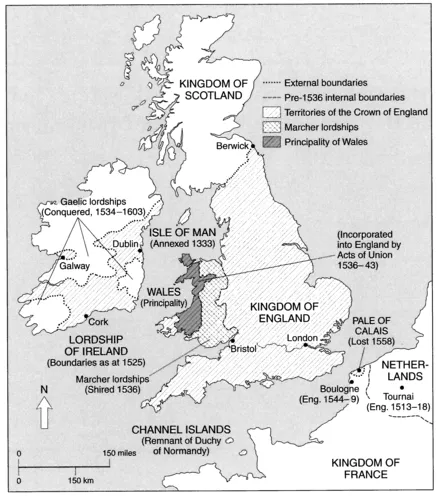

Map 1 Dominions of the Crown of England under the Tudors, c. 1540

![]()

Chapter One

Colonial Englishmen face up to the Tudors

The Tudor dynasty seized control of the Crown of England and of its core territory almost by accident. No rational observer can have been sure of the outcome when the young Henry Tudor, the future Henry VII, invaded England through Wales as the sole surviving- viable leader of the aristocratic Lancastrian faction opposed to King Richard III. Of national identity in the modern sense, he was no clear-cut example, being by birth one quarter Welsh, one quarter French, and half English. His army at the decisive Battle of Bosworth had a large French contingent in it. This was not surprising as he had invaded from France, with significant aid from its monarch, Charles VIII. That there were a thousand soldiers from England's other traditional enemy, Scotland, in his ranks, owed much to the presence of Scots mercenaries in the service of the French Crown. Welsh supporters naturally came in, though not in the numbers Henry might have hoped for. There were exiled English nobles and their followers in the invasion force, and other noble adherents of Henry's Lancastrian faction joined him later, but Henry, like his army, was a product of cosmopolitan neo-feudal political banditry. His claim to the throne was dubious. Backing him was an extreme form of risk-taking in the field of redistributive industry.

That the gamble came off was due to the fact that his opponent, Richard III, proved lo be an even bigger gambler than Henry, who had been forced into this invasion by the collapse of all other options. Richard chose to try to snatch a quick victory by heading a charge against the heart of his rival's army. It was not a necessary decision by a desperate man, as the Tudor propaganda of Shakespeare's Richard III would have us believe. It was a reckless throw by a very brave one. It nearly came off. Henry's standard-bearer was killed, and his dragon standard bit the dust. Henry himself came close to death, but in the event it was Richard III who was killed. Unhorsed, his crown was knocked from his helmet, his body was hacked to pieces, and his helmet smashed into his skull.1

The kingship which the inexperienced Henry so luckily seized that day in August 1485 was recognisably the feudal lordship of England established by force of arms at the Norman Conquest of 1066. Yet it was radically different from that lordship in the sense that it did not draw strength from or add crucial resources to continental metropolitan territories. That was the main significance of the original conquest of 1066 in European terms. That was why William the Conqueror was plunged for the rest of his life into war with an alarmed king of Scots and a deeply threatened king of France.2 The Angevin counts who succeeded the Norman dukes as lords of this cross-Channel territorial complex were even greater rulers than their predecessors. King Henry II, the ablest head of their Plantagenet dynasty, was lord of a feudal empire very much made in France. Culturally he was French. England was a province.3

The Crown of England which Henry VII gamed was the mere wreckage of this once great feudal structure. He was technically still duke of Normandy, but only in that surviving scrap of the once autonomous duchy which was the Channel Islands, and even they had been annexed to the Crown of England by his predecessor Henry III. Purely technically, the kings of England maintained a claim to the throne of France until the early nineteenth century. Originally, between 1316 and 1328, King Edward III of England had had a very good claim to the hereditary succession to the kingdom of France. In that sense, the arguments of Shakespeare's archbishop of Canterbury in the first act of Henry V to the effect that the French had manufactured false precedents to keep the English monarch off their throne have substance behind them. Yet in 1485 this was such an academic point that Charles VIII of France had granted Henry facilities to recruit troops. It was clear that Henry was no threat to France.

What was much less clear was the nature of the bounds of the community of the realm which in practice gave substance to the concept of the Crown of England. Allegiance is about the only word which can be used to describe the sense of 'Englishness' implied by such a body, and then only if used in a broader sense than the purely feudal, though that feudal relationship was still very important for large sections of the ruling classes within the community of that realm. The subjects of English kings were a complex of interlocking communities using different forms of law, speaking several different languages, and adhering to different customs, but they were united by a common status as subjects of the Crown of England and from that status they derived a common identity. It was seldom their only identity, but it was important to them.4

The regions subject to this monarchy were roughly patterned into core and peripheries. About the core there was no doubt, for it was south-east England. One of the factors which had destabilised the regime of Richard III was that his own power-base was a northern one and he lacked support in the south-east. Partly the south-east was dominant because of its agricultural wealth in an age of ineffective drainage techniques which made its lighter soils very desirable. There were, however, other reasons - such as the unique urban development which was London, and the continental background and obsessions of the royal court and government - which made proximity to France and the Low Countries of paramount importance to them. Some peripheries were more peripheral than others. On the mainland of Britain only the north of England was a true frontier zone, and it was a zone confronting a long-established Scottish kingdom with the same sort of feudal framework as England.

Internal frontiers had existed in other marginal regions of England-in-Britain, but by the early Tudor era these frontiers had really closed. Cornwall, for example — despite the survival, especially in its west, of the ancient Celtic tongue had been for centuries securely associated with the English Crown. The Cornish rebellion of 1497 had been against taxation for the defence of the northern frontier against the Scots, and the Cornish rising of 1549 was against the imposition of radical Protestant usages by the government of Edward VI. These were essentially arguments about the terms of association. The defeat of both rebellions and the replacement of uncooperative conservatives among the local ruling class by a new gentry oriented towards the Tudor court and government settled the argument on the terms of the royal government.5 The fact that the Council of Wales and the Marches survived into the seventeenth century did not mean that even in the sixteenth century there were autonomous marcher lordships, militarised to take advantage of a frontier of expansion and exploitation against what was perceived as the alien, fractured world of the Welsh principalities. Edward I had destroyed the Welsh princes. The council was an instrument of royal rule. The government of Henry VIII, helped by an underlying native Welsh tendency to identify with the perceived 'Welshness' of the Tudors, was able to carry through a systematic legislative union of Wales with the English Crown between 1536 and 1543. Such were the advantages to the Welsh nobility and gentry of closer association with government that the union proved very stable.6

On the other hand, in the Lordship of Ireland the community of the Crown of England had a genuine frontier march in the sixteenth century. Like the medieval barons of the Welsh marches, from whom they were often descended, the magnates of England-in-Ireland abutted onto societies which were perceived as being absolutely outwith the community of the realm — as indeed they were, not so much because they spoke Gaelic as because they, in practice, defied the concept of any meaningful political community beyond the bounds of the regional ascendancies into which they were divided. The Old English magnates of the Lordship were very much an active part of the community of the realm owing allegiance to the Crown of England. The trouble was that they were disproportionately disposed to support the Yorkist side, which was ultimately defeated in the struggle for the throne by the rival Lancastrians led by Henry VII. Of course, the English in Ireland claimed the same privileges as Englishmen in England. They denied they might be taxed without the expression of their consent in an appropriate and convenient legislative assembly. It was a view subsequently held by the English in Virginia. Since the barons of Ireland were of French extraction, they naturally thought of a parliament as the appropriate assembly. That the king might have several parliaments in his realm was not in the least odd. The French kings had representative Estates in many of their provinces, and an Estates-General for the whole of the realm.

Nor was it at all unreasonable for the Irish parliament to insist that it could not be bound by the legislation of a parliament held in, say, Westminster. Parliament had normally very limited functions. The Common Law was the king's law, prescribed by custom and usage universal amongst the Englishry, and unalterable in fundamentals, even by the king. Mainly, parliaments were about exceptional taxation and certain aspects of judicial activity. A parliament was a high court, indeed the king's highest court of law. Above all, the king was parliament. It was an aspect of his sovereignty. The whole notion of the sovereignty of parliament beloved of later Westminster politicians was a perversion. It was clearly stated in the by then meaningless formulas of United Kingdom statute even in the early twenty-first century that it is the monarch who legislates, with advice. That the Irish parliament in 1460 tried to limit the king's writ in Ireland under the guise of restating platitudes about its own powers was intolerable, for the aim of the exercise was to protect Richard, Duke of York, a claimant to the throne. It was not a declaration of independence. No parliament could be independent of the reigning monarch who was its most important part, either in person or by representative. It was a move in a civil war.7 Nor had the Yorkist sympathies of the Irish magnates vanished by the time of Bosworth, as they proved by providing the springboard for the first serious strike against Henry's fragile new regime.

With leadership from the powerful Earl of Kildare, the whole Lordship apart from the city of Waterford went over to the first serious Yorkist pretender, Lambert Simnel, who pretended to be the imprisoned Earl of Warwick, in 1487. Simnel had actually been crowned king of England in Christ Church Cathedral, the cathedral of Norse Dublin founded in 1038 by King Sitric, the local Viking ruler. Its bishops had originally been consecrated at Canterbury. Simnel, in this great church of the Lordship, claimed its crown - England's. With 2000 German mercenaries supplied by Margaret, dowager Duchess of Burgundy, and support in Cornwall and Lancashire, the Irish Yorkists invaded England with their associates Lords Lincoln and Lovell in June 1487. Landing in Lancashire, they were defeated at Stoke by King Henry within a matter of days.8

As late as the 1950s and 1960s English historians who mentioned these events in their texts were liable to repeat the then accepted interpretation that this proved how anxious 'Ireland' was to throw off 'English' rule. This was a bizarre misreading of evidence which clearly shouted exactly the opposite. The fact that Sir Thomas Fitzgerald, chancellor of Ireland, died fighting against Henry VII at Stoke in the Midlands of England underlines just how clearly he and his fellow Old English noblemen from the Lordship saw themselves as integral parts of the English political community; so much so that they were following the classic ploy of trying to use forces created on the periphery of the political system to seize power at the centre. It was a hard-fought field, and The Great Chronicle of London records the grim resolution of Martin Schwartz, commander of the German mercenaries, when he realised that the Earl of Lincoln had been unable to rally to the Yorkist standard more than a fraction of the forces he had promised. Both Lincoln and Schwartz died fighting. As a bid for power, this episode was far more serious than, say, Buckingham's rising against Richard III in 1483, a rising in which the future Henry VII, then nobody's candidate for the throne, had played an abortive role.9

In an age when water united and land divided, the Irish Sea was the great inland sea of the English communities, and no monarch could afford to ignore what went on on its western shore. The ease with which the Yorkists had invaded Lancaster after crowning Simnel king of England in Dublin underlined that. It is true that the next pretender to plague Henry VII, the young man Perkin Warbeck who claimed to be the dead Richard, Duke of York, was at his most dangerous during the substantial period when he was entertained and backed by James IV of Scotland. Yet Warbeck's extraordinary political career, which ended on a gallows at Tyburn in 1499, had begun in the city of Cork in 1491, where he had succumbed to heavy local pressure to assume the role of a Yorkist pretender. He spent the winter of 1491—92 in Munster, beginning to learn to speak English among other ploys. He was later to become the focus of a great deal of discontent in England proper, so it is interesting to note that his original backers were in no wise deterred by the fact that he did not yet speak English. The language of the Common Law, in Dublin as much as London, was that eccentric survival of Norman French known as Law French. Most of the Welsh nobility was bilingual in Welsh and English, and the magnates of the Englishry of Ireland were by the sixteenth century as often as not as comfortable in Irish Gaelic as in the slightly archaic Chaucerian English of the Lordship. The most prestigious language among the ruling class of the domains of the Grown of England was probably French, which admittedly few spoke as a native tongue but many knew passing well. Warbeck's last, disastrous foray against Henry VII took the form of a landing in the far west of Cornwall in late 1497, an area where Cornish was still very much the dominant language.10

So any attempt to see 'Ireland' as 'England's first colony' around 1500 entirely misses the point that the Lordship was a march of the kingdom of England. Equally, the Gaelic lordships against which it was set, and with which it interpenetrated, were not bits of 'Ireland' waiting to be more securely attached, but independent regions of a Gaidhealtachd united by culture, by a common cultural language, and by a common repudiation of the concept of the centralised state - even in the very tentative form it had reached in the greater monarchies of Western Europe. United by the galleys which coursed the convenient seas between its regions, that Gaidhealtachd stretched from Kerry to Cape Wrath in the north of Scotland, with a very important detached section in the Wicklow hills and adjacent coast of Leinster. Even here the Irish Sea provided convenient direct access to the rest of the Gaidhealtachd, whether to the north or west. Yet if the modern connotations of the word 'colony' are singularly unhelpful in explaining the nature of the Lordship, there is an important sense in which that Lordship faced the new Tudor dynasty with the only part of the ruling class of their dominions which can be described as colonial Englishmen. These aristocrats were still attracted by the idea of expansion into the lands of Gaelic rulers. Their ancestors had probably been amongst those feudatories most resentful of control, which is one reason why they moved further away from their monarch, to try to re-create the conditions which had obtained in the feudal community of England before the powerful, diabolically clever, and constantly innovative Angevin Henry II succeeded to its throne.11 Nevertheless, their protestations of loyalty were not insincere, for they needed the ultimate resource of the power of the Crown of England should the fortunes of local war run too disastrously against them. The sixteenth-century Englishry of the Lordship were both loyal and defensive of local autonomies. They were very like metropolitan Englishmen in some respects, very different in others. One crucial difference between them and eighteenth-century American Englishmen was that they had transferred a genuinely aristocratic social order to their new homes. Their leading magnates were comfortable in the royal court, except when they were actively trying to overthrow a given monarch. In other respects, their political position prefigured that of future frontier elites created by the territorial expansion of English subjects.

On the other hand, the aristocratic social structure of the Lordship was crucial in shaping its politics. Around the seat of royal government in Dublin, the strict equivalent of London-Westminster down to the duplication of the major organs of administration and the four central courts of the Common Law, there lay the only truly arable territory in the Lordship, the four fertile counties of Dublin, Kildare, Meath, and Louth. This was the Pale, where direct royal administration of a society very ...