![]() I

I

Theoretical Perspectives![]()

1

New Directions in Loss Research

Eric D. Miller and Julie Omarzu

University of Iowa

Most of us experience losses during our lives. Perhaps we even experience relatively minor, ephemeral losses on a daily basis. We might not get the grade we had hoped for on a certain exam, or perhaps a friend rebuffed us at a social event. Usually, upon reflection, we decide that these losses are relatively minor in our lives. We can usually tell someone what major losses we have experienced in life: for instance the death of a sibling, the loss of a romantic relationship, a severe illness experienced by a close friend, and the loss of self-esteem due to harassment at work. These are just a few "major" losses we could mention. Why are they considered major? Perhaps it is because these losses have never really "left" our consciousness. Perhaps we think about them daily; maybe we could, and do, even talk about them at a moment's notice. Maybe they have changed us, for better or worse—but they have greatly affected our lives. Although we may not necessarily have control over whether these loss events occur, we can control how we respond to them.

This chapter (and this sourcebook) attempts to thoughtfully examine the nature of loss in a thorough, scientific manner. However, as the previous paragraph illustrates, loss is not just an academic matter to be dispassionately studied. Loss events can be the most personal and emotional happenings that humans experience. This point should never be underemphasized. As a matter of fact, it is the ultimate reason why loss needs to be studied from an academic and scientific perspective.

What is Loss?

"Loss is nothing else but change, and change is Nature's delight."

—Marcus Aurelius

The origin of the word "loss." One relatively objective way to understand what exactly is meant by "loss" can be achieved by briefly considering the origin and history of this word. According to The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology (1995), the word loss, found in Old English form, was probably first used before 1200 and was synonymous with death and destruction. The word loss was also probably influenced by the word lose, which originally meant "to be deprived of" (p. 443). The term loss suggests that we no longer have someone or something that we used to have.

Loss as defined by college students. An innovative way to understand what precisely is meant by loss is to simply ask laypeople how they would define this term. To this end, Miller et al. (1996) randomly divided students enrolled in a class titled "Loss and Trauma," at The University of Iowa, into two experimental conditions. (This was done on the first day of class.) These two conditions involved the following variations: 74 college students wrote for five minutes regarding a recent major loss experience (defined by the subject); a second group of 74 students wrote for five minutes about a recent joyful experience (defined by the subject). For the purposes of this chapter, we shall only discuss the responses of students who wrote about a recent major loss experience.

Among the questions posed to the students in the "loss" condition were the following two open-ended questions: "Please list in order the first thoughts or images that come to your mind when you think of loss," and "How many major losses have you experienced in life to date? Please briefly identify each with two or three words or phrases."

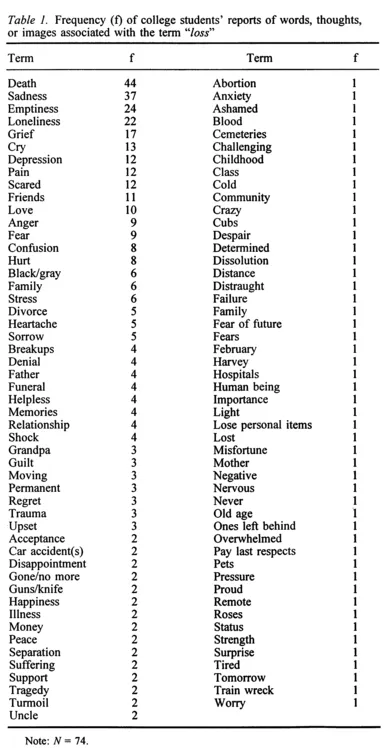

Table 1 lists all of the words, thoughts, or images that students associated with the term loss. After examining these terms, it becomes clear that most students tend to view loss as a negative occurrence. In particular, the nine most frequently listed terms appear to have clear negative connotations. Moreover, very few terms tend to overtly convey a sense that loss is or can be a positive event (i.e., associated with psychological growth). Another intriguing finding is that nearly half of all terms provided were stated only once by the entire sample; this may further suggest that loss is an event that affects individuals in very idiosyncratic ways.

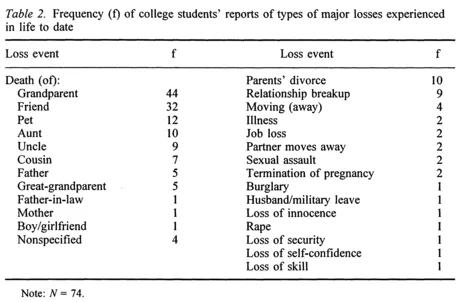

Nearly 60% of the students (N = 44) associated the term loss with death; this term was, in fact, the most common word associated with loss. This theme is also quite prevalent in the descriptive data from Table 2. Table 2 lists all of the types of major losses that college students experienced in life to date. The 74 students who responded to this question listed a total of 171 loss events. Of these 171 loss events, 131 events (76.6%) were loss events involving death. It appears that the term loss serves as a memory prime for the term death. However, this study was conducted on the first day of class; it is possible that in the final weeks of the class their answers may have provided more variation.

Is loss research synonymous with the study of death? Based on the responses from the study described above, one might be tempted to answer this question affirmatively. Clearly, though, death is only one form or type of loss that a person can experience.

Loss can take many different forms. Harvey (1996a) offers a sampling of the many different types of losses that we may endure, including loss of biological parents early or late in life due to death, loss of health because of disease or injury, loss of home because of poverty, loss of contact with friends because of one party moving, loss of peace of mind, war-time trauma, and victimization due to domestic abuse or crime. Surely, the chapters in this sourcebook also present many other intriguing and interesting types of losses. Ultimately, Harvey (1996b) suggests that a major loss is an event involving a significant diminution in one's resources. Moreover, as Rando (1988) posits, there are two basic types of losses:

physical losses, where something tangible has been made unavailable (e.g., death of a spouse), and symbolic losses, where there are abstract changes in one's psychological experiences of social interactions (e.g., losing status as a result of job demotion).

Yet, the question still remains: why are the terms loss and death often used interchangeably? To be sure, the majority of studies pertaining to loss tend to focus on death. Solomon, Greenberg, and Pyszczynski's (1991) terror management theory suggests why death is the ultimate form of loss. In short, the authors argue that thinking about one's death creates the potential for terror, since we may feel as though we are living meaningless lives. But perhaps there is an even simpler reason why death is the ultimate form of loss. Although all losses have the potential to cause pain and suffering, death is a special and unique form of loss. We can recover our sense of self-worth; we can receive organ transplants or artificial limbs; we can even remarry the same person whom we divorced. Death is probably the only type of loss that can never be recovered: death is loss forever.

Moving beyond Traditional Definitions of Loss

Why loss is an important topic to study. As we suggested from the outset of this chapter, the ultimate reason why loss is such an important topic to study is that it can truly have a dramatic, everlasting impact on the lives of people. Actually, we would argue that no one really is immune to the experience of loss.

Although some people seemingly withstand transitions and tragedies better than others, it would be difficult for any one of us to pass through life without experiencing a major loss or upheaval of some kind. Death robs us of people we love. Illness or disability may cause us to lose treasured abilities or force us to abandon some dreams. Social changes cost us jobs, friendships, or social status. Loss is an everyday, common event. As such, it has an impact on human emotion, cognition, and behavior that merits concentrated study on the part of social and behavioral scientists. Without an understanding of how people cope with and perceive loss experiences, we cannot hope to completely understand human nature.

Harvey and Weber (in Chapter 24 of this volume) provide many more thoughtful reasons why there must be a psychology of loss, and they discuss how loss has been represented in contemporary society. We would like to briefly extend that discussion by providing some recent anecdotes of how the topic of loss now pervades (American) popular culture.

To be sure, the importance of loss events can be most easily seen in the prevalence of loss themes and images in popular culture. Funerals are among our most powerful social and religious ceremonies. Kübler-Ross' (1969) "stages-of-grieving" model has become common knowledge in our society. Support groups abound for almost every type of loss experience imaginable, from death of a child to unemployment.

Loss clearly was a major theme in the 1996 U.S. Presidential election. Many were moved by Vice President A1 Gore's tribute to his deceased sister at the Democratic National Convention; likewise, many were moved by the life-long ability of Republican standard-bearer, Bob Dole, to overcome his personal war injuries. Although President Clinton was ultimately reelected, many consider that "The Comeback Kid" may not have won had it not been for a major crisis, namely, the Oklahoma City bombing (Mitchell, 1996). On a related topic, Celente (1997) forecasts that the Oklahoma City bombing is only the beginning of a new wave of horrific terrorism that will sweep across the United States. Clearly, the psychological consequences of terrorism are still understudied.

The themes of loss can easily be found in contemporary music and movies. For instance, the song "One Sweet Day," by Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men—which is ranked as one of the longest-running "Number 1" pop single in "Hot 100" history, according to Billboard magazine (Bronson, 1996)—deals with the hope that deceased friends have found peace in the afterlife. In addition, many of the recent Academy Award-winning Best Pictures have had loss as central plot themes. In a recent column, Goodman (1996) suggested that the classic film It's a Wonderful Life has more relevance today than it did when it was released in 1946, due to the harsh realities of contemporary American life. If nothing else, Americans were inundated with the theme of loss via the ongoing O. J. Simpson saga.

These examples from popular culture are not intended to serve merely as provocative stories. Rather, they show that the theme of loss is strongly embedded within contemporary American culture and society. This is another reason why it is essential to conduct loss research.

The study of loss is not yet a fully recognized academic discipline. How do people cope with different types of losses? What makes up the experience of loss? Do different kinds of loss events produce similar emotions and behaviors? What is happening when someone talks about "recovering" from a loss; what has changed? Why are some people more affected than others, and how can we help them? Is there a way to satisfactorily explain the loss experience so that we may better understand it and grow from it? While these questions have been examined by researchers, none has been definitively answered.

We contend that, at this point, the current literature in most loss research topics is largely disjointed, disorganized, and descriptive. It is a given that loss researchers must be fully aware of all developments in their respective areas of research. Moreover, we are not simply arguing that more loss research needs to be done. Rather, we suggest that too much loss research has been conducted that has not been grounded in a larger theoretical context. In addition, there needs to be more overall integration in the area if it is to be recognized as its own independent discipline.

This point can be dramatically illustrated by considering the paltry amount of research that developmental psychologists have conducted about how children cope with the death or illness of a parent. Siegel et al. (1992) note that while this topic has been considered in the clinical literature, most of the studies have been descriptive. Issel, Ersek, and Lewis (1990) add that "virtually no research has focused on the impact of a parent's chronic physical illness on school-age children. Consequently, the effects of parental illness such as cancer on school-age children are poorly understood and warrant empirical investigation" (p. 5). Not only is it puzzling that this topic has been largely ignored, but it is just as surprising that developmental researchers have not made vigorous attempts to link this topic with the larger theoretical models of attachment (Bowlby, 1969, 1980), internal working models (Bretherton, 1985; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985), and the emotional security hypothesis (Cummings & Davies, 1994).

In sum, we maintain that unless loss research is placed within pre-existing or newly developed theoretical models, this area will continue to be disjointed.

Previous models of loss and how they differ from what we are discussing. Much early loss research was derived from Freud's (1957) psychoanalytic ...