![]()

1

Issues in writing research and instruction

1.1 Introduction

Applied linguistics has concerned itself with the development of writing skills for at least the past 50 years, and that it has done so is entirely appropriate. If one is to take seriously the relatively straightforward definition of applied linguistics as the attempt to resolve real-world language-based problems, then the development of writing abilities, whether for learners of English as a first language (L1), or as a second language (L2), or learners of any other language, surely falls well within the domain of applied linguistics.

There are, however, significant differences between the two groups of learners, since there are wide variations in learner issues within each of these major groups. These differences and their consequences for writing theory and instruction will be explored throughout the book. The treatment of both groups within a single volume is, however, the only logical applied linguistics perspective to adopt since both groups subsume learning and instructional problems which are language-based, and there is significant overlap in their historical evolution over the past 20 years. The decision to ignore English first-language research and practice would not only lead to a badly distorted view of L2 writing approaches, it would also misinterpret the true scope of applied linguistics inquiry with respect to issues in writing development.

This chapter outlines many of the larger issues and problems implicit in the theory and practice of writing instruction, adopting a broad applied linguistics perspective. In exploring issues in writing, basic assumptions about the nature of writing must be considered. For example, why do people write? That is to say, what different sorts of writing are done by which different groups of people, and for what different purposes? More fundamentally, one must ask: What constitutes writing? Such basic questions cannot be discussed in a vacuum but must also consider the larger issues raised by literacy skills development and literacy demands in various contexts. Literacy, incorporating specific writing issues with a related set of reading issues, highlights the necessary connections between reading and writing as complementary comprehension/production processes. It also introduces the distinctions between spoken and written language forms, and the specific constraints of the written medium. Thus, a brief overview of literacy provides an important background for understanding the recent developments in writing theory and instruction.

Any discussion of basic foundations must necessarily incorporate outlines of research on both writing in English as the first language and writing in a second language. From the LI perspective, many theoretical issues and concerns in LI contexts also affect writing approaches in L2 situations. From the L2 perspective, research in L2 writing also highlights differences between the two contexts. The many additional variables introduced in L2 contexts — not only cognitive but also social, cultural and educational - make considerations of writing in a second language substantially different in certain respects.

This chapter also explores the gap between research and instruction and considers how that gap may be bridged. The translation from theory to practice in LI writing contexts has changed considerably over the past 20 years. Such a translation has also had a profound impact on L2 applications from theory to practice; some of these applications have been appropriate, while others have been much less appropriate, given the distinct L2 context. For example, L2 instruction may:

- place writing demands on EFL students, and for some of them, English may not be perceived as a very important subject;

- place distinct writing demands on English for Special Purposes (ESP) students, or on English for Occupational Purposes (EOP) students - demands which may be very different from those on English for Academic Purposes (EAP) students planning to enter English medium universities;

- include writing demands on adult literacy and immigrant survival English students - both groups experiencing very different demands from those which occur in academic contexts;

- include academic writing demands in which a sophisticated level of writing is not a critical concern.

All of these issues form parts of an overview of writing theory and practice from an applied linguistics perspective.

1.2 On the nature of writing

The need for writing in modern literate societies - societies marked by pervasive print media - is much more extensive than is generally realized. When one examines the everyday world, one finds people engaged in many varieties of writing, some of which may be overlooked as being routine, or commonplace, or unimportant. These varieties, however, all represent the ability to control the written medium of language to some extent. It is fair to say that most people, on a typical day, practice some forms of writing. And virtually everyone in every walk of life completes an enormous number of forms. In addition, many people write for reasons unrelated to their work: letters, diaries, messages, shopping lists, budgets, etc.

Describing the various tasks performed every day by writers offers one way of classifying what people write, but a slightly more abstract taxonomy of writing types will prove more descriptively useful. A list of actual writing tasks does not provide a way to group these tasks according to similar function - a goal in understanding what gets written and why. In fact, many different functional sorts of writing constitute common occurrences. These sorts of writing, depending on the context, task, and audience, may be classified functionally in numerous ways, including writing to identify, to communicate, to call to action, to remember, to satisfy requirements, to introspect, or to create, either in terms of recombining existing information or in terms of aesthetic form. Thus:

- writing down one's name identifies

- writing a shopping list may identify, communicate, and/or remind

- writing a memo may communicate and remind

- writing a student essay may at least satisfy a requirement

- writing a diary may promote introspection

- writing a professional article may communicate, recombine, and allow introspection

- writing a novel or a poem may exemplify what is known as aesthetic creativity.

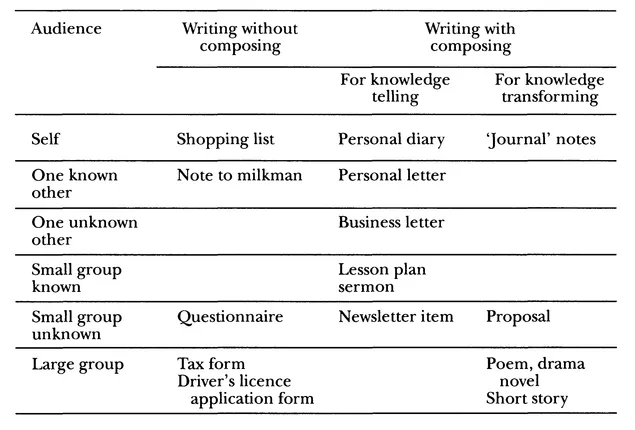

At yet another development level, one may distinguish writing which involves composing from writing which does not; this distinction is useful because most of what is referred to academically as writing assumes composing. Composing involves the combining of structural sentence units into a more-or-less unique, cohesive and coherent larger structure (as opposed to lists, forms, etc.). A piece of writing which implicates composing contains surface features which connect the discourse and an underlying logic of organization which is more than simply the sum of the meanings of the individual sentences. Figure 1.1 illustrates the composing/ non-composing dichotomy in terms of audience. The matrix suggests the possible options that are available for writing with or without composing.

Figure 1.1 Patterns of composing with differing audiences

Composing, further, may be divided into writing which is, in essence, telling or retelling and writing which is transforming. Retelling signifies the sort of writing that is, to a large extent, already known to the author, such as narratives and descriptions. The planning involves recalling and reiterating. Transforming, on the other hand, signifies that sort of writing for which no blueprint is readily available. The planning involves the complex juxtaposition of many pieces of information as well as the weighing of various rhetorical options and constraints (Bereiter and Scardamalia 1987). In this type of writing, the author is not certain of the final product; on the contrary, the writing act constitutes a heuristic through which an information-transfer problem is solved both for the author and for his or her intended audience. This notion of composing is much more comprehensive than the idea of drafting or 'shaping at the point of utterance' (Britton 1983), since it takes in the 'final' product. Many sorts of what traditionally have been labelled expository and argumentative/persuasive texts, as well as 'creative' writing, involve transforming. In Figure 1.1, an attempt has been made to distinguish between retelling and transforming, even though both organizing strategies are available for many sorts of composing.

In most academic settings where students are learning to write, the educational system assumes that students will learn to compose with the ability to transform information. In fact, many students learning to write before they enter the tertiary level have little consistent exposure to writing demands beyond retelling. In some cases, students, both in LI and L2, have minimal practice even with simple retelling. The problems created by these students as they enter the academic environment certainly deserve the attention of applied linguists. Moreover, writing places constraints on student learning that are distinct from the development of spoken language abilities.

To understand these developmental constraints on students, and the more complex demands made by academic institutions, it will be useful to examine briefly the historical development of writing and the changing writing/literacy expectations which have arisen over the last two centuries.

Writing is a rather recent invention, historically speaking. Unlike spoken language - coterminous with the history of the species - written language has a documented history of little more than 6000 years. And while it is generally accepted by linguists that certain aspects of spoken language may be biologically determined, the same cannot be said of writing. While all normally developing people learn to speak a first language, perhaps half of the world's current population does not know how to read or write to a functionally adequate level, and one-fifth of the world's population is totally non-literate. It seems a bit absurd to suggest that this difference is accidental, due to the inaccessibility of writing instruments or material to read. Nor does it seem appropriate to label this one-fifth of humankind as somehow 'abnormal'.

The distinction between spoken and written media calls attention to a significant constraint on the development of writing abilities. Writing abilities are not naturally acquired; they must be culturally (rather than biologically) transmitted in every generation, whether in schools or in other assisting environments. While there are many distinctions between the two media in terms of lexical and structural use, the acquired/learned distinction deserves particular attention. The logical conclusion to draw from this distinction is that writing is a technology, a set of skills which must be practised and learned through experience. Defining writing in this way helps to explain why writing of the more complex sorts causes great problems for students; the skills required do not come naturally, but rather are gained through conscious effort and much practice. It is also very likely, for this reason, that numbers of students may never develop the more sophisticated composing skills which transform information into new texts.

The crucial notion is not that writing subsumes a set body of techniques to master, as might be claimed, for example, in learning to swim; rather, the crucial notion is that writing is not a natural ability that automatically accompanies maturation (Liberman and Liberman 1990). Writing - particularly the more complex composing skill valued in the academy - involves training, instruction, practice, experience, and purpose. Saying that writing is a technology implies only that the way people learn to write is essentially different from the way they learn to speak, and there is no guarantee that any person will read or write without some assistance.

1.3 Literacy and writing

The history of literacy development supports such a writing-as-technology perspective for the nature of writing. Indeed, a number of literacy scholars have argued for this view strongly; any other definition of literacy does not stand up to the historical evidence (Goody 1987, Graff 1987). Since there are, in fact, many types of literacy which have developed historically under very different contexts and for very different uses, any more complex definition tends not to hold up equally well in all contexts (cf. Cressy 1980, Graff 1987, Houston 1988, Purves 1991). Moreover, the history of literacy demonstrates that reading and writing skills were developed and passed on to following generations only in response to cultural and social contexts; these skills were not maintained when appropriate social and cultural supports were removed.

In fact, the definition of writing-as-technology fits extremely well with historical perspectives on literacy because many literacy movements and developments were little more than the wider dissemination of very basic skills, such as the ability to write one's name or fill out a ledger or a form. Such literacy developments hardly count as the sort of writing-as-composing discussed earlier or as the type that is valued academically; yet, these literacy developments undeniably reflect aspects of writing abilities.

The history of literacy development is both enlightening and commonly misunderstood. It is enlightening because the many and varied literacy movements and contexts of literacy development provide a better understanding of the current use of, and expectations for, students' writing abilities; it is often misunderstood because many assumptions about literacy have been widely promoted and accepted without careful documentation and analysis (cf. Graff 1987). One significant point that the study of literacy has demonstrated, both synchronically and diachronically, is that there are many different sorts of literacy skills just as there are many different sorts of writing abilities. Most students who display writing problems in educational contexts do, in fact, have writing skills; they are just not the skills which educational institutions value (Barton and Ivanic 1991, Street 1993). This is particularly true for L2 students in EAP contexts; they clearly come to higher academic institutions with many different literacy practices and many different views on the purposes of reading and writing.

The history of Western literacy begins (from c. 3100 BC) with the early uses of writing for recording events, traditions, and transactions by scribal specialists who were able to translate orally for the masses as was necessary. The powers of priesthood can be attributed to the apparently mystical properties associated with the ability to read and write. The rise of the Greek city-states signalled a greater dissemination of literacy skills among the populace. However, literacy among the classical Greek citizenry was less widespread and less sophisticated than has commonly been assumed. Perhaps only 15-20 per cent of the Greek population consisted of 'citizenry', and oral traditions were still the trusted and preferred means of communicating. Similarly, the Roman period was marked by a limited literacy among the populace; in this context, literacy was due in large part to the rise of public schooling, the need for civil servants to do government business in the far-flung regions of the empire, and the rise of commercial literacy needs. Nevertheless, it was a very small intellectual, political, and religious elite that possessed literacy skills (cf. Goody 1987, Graff 1987).

The decline of Rome saw the role of literacy relegated primarily to the religious infrastructure which emerged across Europe from the fourth to the eighth century. While many schooling traditions of the Roman era persisted throughout Western Europe, most were taken over by the church for the training of priests, clerics, and other functionaries. The development of literacy for other than religious uses began during the eighth to tenth centuries; and contrary to popular belief, the 'Dark Ages' was not a period of complete illiteracy beyond the monastery walls. The tenth and eleventh centuries marked the beginnings of a commercial literacy and set the stage for literacy practices across Europe from the twelfth to the fifteenth century. It is evident from the research of such scholars as Harvey Graff that literacy has a continuous history in Europe from the Greek city-states to the present. What must also be understood is that literacy was still restricted, tied to church, state, or economic necessity, and to particular practices in particular contexts. The mass literacy to which we are accustomed simply did not exist and, during most of this time, the ability to compose was extremely limited.

As noted above, religious institutions played a critical role in the history of Western literacy. It was not until the evolution of Protestantism in the sixteenth century that popular literacy became necessary. Unlike the Roman Catholic church, Protestant theology took the view that personal salvation could be achieved through direct access to the biblical gospels. Protestant sects have contributed importantly to world literacy through missionary activities which supported the translation of the Bible into hundreds of non-Indo-European languages as well as the teaching of literacy in the languages of the missionaries (e.g. English, French, German, Spanish) for purposes of access to the Bible in European languages (e.g. the work of the Summer Institute of Linguistics and the Wycliff Bible Translators).

The first well-defined popular literacy movement in Europe may arguably be traced to the English revolution and the rise of Oliver Cromwell or to Martin Luther and the Protestant reformation. (The earlier development of Hangul in Korea should not be overlooked, though it is unlikely that literacy beyond the aristocracy was a serious objective.) The clearest early case of a successful mass literacy movement, however, is attributable to the Swedish movement of the seventeenth century to require of all Swedish citizens the ability to read the Bible (Arnove and Graff 1987, Graff 1987). This movement was remarkably successful since reading the Bible was a prerequisite for religious confirmations, and confirmation in the church was a requirement for marriage. For the first time, women as well as men were trained in literacy skills. This literacy campaign, however, as in much of the previous history of literacy, concentrated almost exclusively on reading, and in particular on reading the Bible. The role of writing in common literacy development can only be seen as an innovation of the last 200 or so years. Even rudimentary writing skills (beyond signing and recording) among the populace were unknown until very recently.1

In the modern historical era, the rise of popular literacy including the uses of writing for secular purposes beyond government and business - emerged in the late eighteenth century, primarily in England, France and the USA. As traced by Cook-Gumperz (1986; see also Resnick and Resnick 1977), the rise of modern literacy (including writing skills) can be seen as occurring in three stages. Roughly, the period between 1750 and 1850 can be considered to mark the rise of common literacy (not school-directed or taught). In the mid-nineteenth century, parts of continental Europe, the UK, and the USA supported the rise of schooled literacy along with the beginnings of compulsory education. Literacy then became a means...