This is a test

- 410 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rhythms of English Poetry

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Examines the way in which poetry in English makes use of rhythm. The author argues that there are three major influences which determine the verse-forms used in any language: the natural rhythm of the spoken language itself; the properties of rhythmic form; and the metrical conventions which have grown up within the literary tradition. He investigates these in order to explain the forms of English verse, and to show how rhythm and metre work as an essential part of the reader's experience of poetry.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Rhythms of English Poetry by Derek Attridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Traditional approaches

One kind of insight into the history of metrical study in English can be gained simply from a glance at the collections on the subject held by most large, long-established libraries. The shelves are dominated by fading volumes from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: unwieldy surveys thick with scanned quotations; elegant essays dabbling in this or that prosodic sidestream; scientific investigations of syllabic duration or vocalic quality; handbooks for the schoolroom parading lists of Greek terms and recherché metres culled from Swinburne and Bridges. Most of these works evince a deep passion for the subject: absolute truths are proclaimed in heavy capitals, opponents despatched in savagely civil footnotes, snippets of verse triumphantly displayed like newly-discovered zoological specimens. Very few fail to offer some illumination of a corner or two, or to provide some problematic example which demands an explanation; but by and large their undisturbed repose on the library shelves is not unmerited.

Within this vast demonstration of scholarly and critical ardour ranging from the comically idiosyncratic to the laboriously obvious it is possible to trace two main approaches to English metre, and these form the subject of this chapter. To categorise in this way is, of course, to over-simplify and misrepresent a complex web of arguments; but the survey that follows is intended not as a history of prosodic study, but as an examination of those ways of dealing with metre which have proved most tenacious in their hold on the English literary consciousness, and which are most likely to affect – whether we realise it or not – our present reading, teaching, and criticism of verse. This examination will have the double aim of providing an outline of the metrical assumptions which underlie most critical discussions of English poetry, and of assessing what is valuable and what misleading about these traditional accounts. While prosodic approaches of more recent origin, to be discussed in the next chapter, have begun to make themselves felt in literary criticism, it is still true to say that most comments on the rhythms of English poetry owe their existence to theories which bear the dust – or the patina – of centuries upon them.

1.1 THE CLASSICAL APPROACH

When, in the sixteenth century, English poets, scholars, and educators joined the general European revaluation of classical literature, and set the verse of Greece and Rome on the highest of pedestals, it was inevitable that the literary endeavours of Englishmen in their own language should come under fresh scrutiny, and equally inevitable (until the last quarter of the century) that in the ensuing judgement the home-grown product should be found wanting. One obvious respect in which English verse failed to match the high art of the ancients was in its apparent lack of metrical organisation and subtlety, since the only tools of analysis possessed by the early humanists were those of classical prosody, and these afforded no purchase on the lines of English poets. The syllables of the English language, unlike those of Greek and Latin, had not been definitively classified by means of minutely detailed rules and the hallowed example of great poets, and any attempt to scan English verse by the familiar procedures of classical prosody revealed only chaos. To be sure, the sound of English verse had a kind of crude regularity, but very few educated readers expected to find the principles of metrical patterning so obviously in what they heard: they read Latin verse with a mode of pronunciation which gave no aural embodiment to its metrical structure, and their sense of its fine artistic precision came from an intellectual perception of the ordered ranks of abstractly categorised syllables.1

One natural result of this dissatisfaction was the protracted endeavour by English poets to create in their own language an equivalent of classical metrical forms: the efforts of some thirty writers survive from between 1540 and 1603, including examples by Ascham, Sidney, Spenser, Greene, and Campion. Although some of this ‘quantitative’ verse achieved critical acclaim and a degree of popularity, by the end of the century it was evident even to the most diehard humanist that poetry in the native accentual tradition had come closer to equalling the achievements of Greece and Rome than any imitations of classical metres, and that a more valuable enterprise might be the study of the indigenous verse forms created by English poets without prosodic apparatus and scholarly effort. But in the absence of any phonetic analysis of the English language, or even any vocabulary with which to begin such an analysis, those undertaking the task naturally fell back on the only metrical terminology they possessed – that of classical prosody – and applied it to the native English forms. In doing this, they were drawing on procedures which the humanist education instilled at an early age: Prosodia formed the fourth section of Lily’s grammar, on which the Elizabethan grammar school syllabus was founded, and it was the intention, as a 1612 handbook for teachers put it, to make all boys ‘very cunning in the rules of versifying’ and ‘expert in scanning a verse’ (Brinsley, p. 192).

Nevertheless, the exact manner in which classical terms and methods of analysis were to be transferred to English verse was far from obvious: George Gascoigne, the father of English metrical studies, is unusual in clearly perceiving the alternating stresses of English metre, but he identifies English stress with both ‘grave’ and ‘long’ syllables in Latin, thus combining the separate features of accent and quantity (1575, pp. 49–51). He initiates a long tradition by using the term ‘foot’ to refer to accentually-based subdivisions of the English line, and laments that only one type is employed by English poets; but he does not associate it specifically with the classical iambic foot. Three years later, however, Thomas Blenerhasset, commenting on the metre of his ‘Complaint of Cadwallader’, states that it ‘agreeth very well with the Roman verse called Iambus’ (1578, p. 450); and by 1586 William Webbe can remark that ‘the natural course of most English verses seemeth to run upon the old Iambic stroke’ (p. 273). And so the terms of classical prosody became lodged among the commonplaces of English metrical analysis, in spite of the sharp differences between the two languages and their prevailing metrical forms. The understanding of metre implied by these terms, which for convenience we can call the ‘classical’ approach, was not systematically elaborated for some time, however: the main tradition in prosodic theory until the end of the eighteenth century was based on syllables and accents rather than feet,2 and only with the new interest in Greece and Rome in the nineteenth century did foot-scansion come into its own as a mode of analysis, accompanied by another round of experiments in English classical metres.

It is important to see this approach to metre in its historical context, and to understand how it came into being, so that its sheer familiarity does not confer on it any unwarranted authority. Latin is no longer a staple educational diet from an early age, and we should therefore find it easier than our forebears to question the appropriateness for English verse of terms and concepts borrowed from an ancient language, which were themselves a borrowing from an even earlier one. Nevertheless, because of its importance in the writing of both poets and critics, the outlines of the classical approach, at least, have to be mastered by anyone with an interest in English poetry. What follows is a mere sketch of its commonest form: upon this simple foundation much more elaborate theoretical edifices have been erected to take account of the huge variety in English metrical practice, but these should be consulted in their original presentations.3

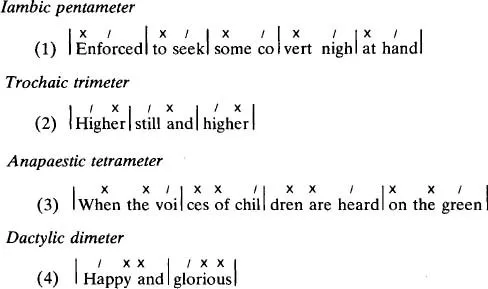

The classical approach to English metre takes as its fundamental unit the foot, a group of syllables each of which is defined as stressed or unstressed, matching the ‘long’ and ‘short’ of the classical originals. Most English metres consist of the same foot repeated a fixed number of times, and the traditional names of the metres derive from the type of foot and the number of its occurrences in the line. The following list contains the essential vocabulary of the classical approach, x standing for an unstressed syllable, or nonstress, and / for a stress (a less misleading notation than those which retain one or both of the classical symbols for long and short syllables):

(a) Types of foot

x / | iambic foot or iamb |

/ x | trochaic foot or trochee |

x x | pyrrhic foot or pyrrhic |

/ / | spondaic foot or spondee |

x x / | anapaestic foot or anapaest |

/ x x | dactylic foot or dactyl |

(b) Types of line

monometer | one foot |

dimeter | two feet |

trimeter | three feet |

tetrameter | four feet |

pentameter | five feet |

hexameter or alexandrine | six feet |

heptameter | seven feet |

octometer | eight feet |

Since the English language is incapable of a long succession of either stressed or unstressed syllables, it will be obvious that of the six kinds of foot listed, only those which include syllables of both types can be used as the foundation of a simple metre, producing four main varieties of verse. Those which make use of the two-syllable feet are said to be in duple or binary metres, those which use three-syllable feet in triple or ternary metres. The following are examples of the four types of metre in differing line-lengths:

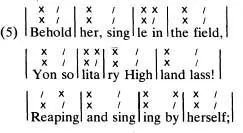

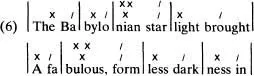

In order to relate these simple schemes to the much more varied lines which poets actually write, the classical approach has recourse to the notion of substitution, according to which the feet of the basic metre can be replaced by other feet. Thus a trochee can be substituted for an iamb, and vice versa; and a spondee or a pyrrhic for either. The following lines will serve as an illustration, the lower set of symbols indicating the basic metre, and the upper set the actual stresses and nonstresses of a possible reading:

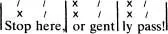

In the basic metre, three lines of iambic tetrameter are followed by an iambic trimeter. However, each of the three tetrameters has one pyrrhic substitution; the third line begins with a trochaic substitution (often called an inversion, and in this position an initial inversion); and the final line begins with a spondaic substitution. It is also possible to replace a duple foot by a triple foot; this is known as trisyllabic substitution, and its most common form involves the doubling of the unstressed syllable to replace an iamb by an anapaest, or a trochee by a dactyl. Thus in the following example the iambic tetrameters are varied by means of an occasional anapaestic substitution (I show only the substituted feet on the upper level):

Triple metres are dealt with on the same principle, though less elegantly, since the many possible substitute feet demand further raids on the stock of Greek prosodic terminology.

Another classical term inherited by English prosody with a changed signification is caesura. In the analysis of English verse it is used to refer to a pause within the line created by the syntax; thus one can say that in (5) the first and the fourth lines have a prominent caesura, the former after the third and the latter after the second syllable. The term does not refer to anything in the structure of most English verse, however, and there is no reason to prefer it to ‘pause’ or ‘syntactic break’ in describing a line. Two other terms, of more value in metrical discussion, can be introduced here: a line which ends with a syntactic break is end-stopped, and one which does not is run-on (or enjambed). All the lines in (5) are end-stopped; the first line of (6) is run-on. It is also worth mentioning a metrical phenomenon which the classical approach does not easily accommodate: lines of iambic verse may have an extra unstressed syllable, or occasionally two, after the final stress; these are, respectively, feminine and triple endings (as opposed to the masculine ending which terminates the line on a stress), and have to be regarded as ‘extrametrical’. We shall see in due course that the endings of much trochaic verse also create problems for the classical approach.

What I have described is merely a mode of scansion, but it implies a particular conception of poetic rhythm: a simple underlying metre on which is superimposed a more complex pattern representing with greater fidelity the actual pronunciation of the words. Most modern defenders of the classical approach would argue that this picture of two levels, partly coinciding, partly conflicting, reflects what in fact happens as we read metrical verse, and reveals one source of its special character. Many attempts have been made to capture the level of actual pronunciation by means of an analysis more delicate than that provided by classical prosody, and we shall consider some of these in 1.2 and 2.1 below. But however the two levels are represented, the notion of the interplay, or counterpoint, or tension, between a simple metrical pattern and a more varied arrangement of stresses corresponding to the pronunciation of the line in one of the most suggestive features of the classical approach, and one to which we shall return.

Let us now subject the concept of the foot itself to closer scrutiny, without allowing ourselves to be awed by its classical pedigree. At the heart of the analysis of English verse in terms of feet is the understanding that the line is constituted by a series of repeated events, and that its character is determined in part by the number of those repetitions; thus a tetrameter has a distinctively different quality from that of a pentameter. English verse is shown by this means to be different from, say, French or Italian verse, in which there are no such repeated syllabic groups. So far so good; but the rub is that in offering this insight into the structure of the lines, the classical ap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Part One: Approaches

- Part Two: Rhythm

- Part Three: Metre

- Part Four: Practice

- APPENDIX: RULES AND SCANSION

- Bibliography

- Sources of examples

- Index