![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

Most planners, landscape architects, architects and engineers have an environmental ethic as well as an eagerness to improve the wellbeing of people. The contradiction of advancing ecologically focused (ecocentric) and anthropocentric values simultaneously may explain the gap between philosophy and what we have built over the last five decades. This ethical dualism arises because the professions are hetero geneous in practice types and application scales. Therefore, many design professionals may focus on the parcel scale and not see the cumulative impact of their work. Also, for many professionals the absence of opportunity and the lack of knowledge might explain ineffective or insufficient application of sustainable urban design. Consideration of environmental values and anthropocentric practice is clouded by a veneer of sustainability rhetoric and a focus on the site scale rather than on the larger, more important issues impacting local ecosystems. The small population of professionals engaged in the planning and design of the built environment may also dampen the expectation that individuals, or even the whole profession, can make meaningful stewardship contributions toward solving the worldwide problems of poor human health, habitat loss, species extinctions, global warming, etc.

Value systems

Ecocentric values

The ecocentric perspective posits that every species should have an equal survival opportunity.1 An estimated 21–36 percent of the world’s mammal species, 13 percent of birds, 30–56 percent of amphibians and 30 percent of conifers are threatened with extinction. The number of threatened species has increased in every category since 1996. In 1996, for example, 3,314 species were in the threatened, endangered and critically endangered categories, compared to 7,108 in 2011.2

Fossil records provide us with a normal extinction rate, with the exception of the few mass extinction events, for the earth’s history. Today the species extinction rate is 600–6,000 times the normal rate indicated by the fossil record.3 The primary cause of extinctions and biological diversity (biodiversity) reductions is habitat loss.4 The rapid growth of the human population and the conversion of land to human use is the reason that the survival of so many species is threatened. Clearly, the ecocentric ethic does not guide enough human decisions to secure the survival of thousands of other species. Is it immorality, ignorance, impotence, unrecognized cumulative impact or intractable problems that result in such destructive behavior by governments, professions and individuals? Have the seven billion humans simply exceeded the carrying capacity of the planet? These are troubling questions and the planning and design professions can begin to address only a few of them. However, there are many opportunities for the design professions to positively impact the lives of people and their relationship to the survival of other species. This book explores the values, concepts, knowledge areas, planning processes and detailed design techniques that lead to positive human and ecosystem outcomes.

Anthropocentric values

Urban design professionals are anthropocentric in their processes and outcomes.1 The anthropocentric perspective gives humans an elevated status based on philosophical or religious foundations, or simply through overwhelming self-interest. It also expresses man’s relationship to the environment in terms of resource management, husbandry of some species or ecosystems instead of others, or conversion of the natural world for the economic and cultural benefit of humans (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Sprawling low-density residential development at the edges of all American cities is represented in this view of Tucson, Arizona. The energy, climate, habitat and other impacts of this growth are well understood and better models have been demonstrated. Photo 32°12'43.87" N 110°51 '23.93" W by Google Earth.

When involved in community planning or master planning of large developments, landscape architects use participatory and strategic planning processes to resolve conflicts among competing interests. In a deliberative democracy, decisions about land and resource use are social decisions that, ideally, involve the clear communication of information, goals, interests and power relationships. Unfortunately, economic self-interest, political philosophies and social prejudices are all involved in this process, with the possible effect of subverting or corrupting the democratic process. From the perspective of power relationships, the strongest interests and values in the planning process will determine the character of the outcome. Human, and especially economic, interests dominate planning and design solutions since the process itself is anthropocentric.1 The empirical expression of this is the relentless expansion of suburbs. At the current rate of suburban growth we can expect more that 60 million acres of land in the US to be converted within a few decades.

Green infrastructure

Human population growth leads to the loss of biodiversity. The world population is expected to grow from 7 billion to 9.1 billion,5 while in the US the change from 309 million to 439 million is expected by 2050.6 The twin impacts of population growth and low-density residential housing are causing more damage than the envir on ment can sustain. Either reductions in population growth or new strategies for high-quality and higher-density residential living are necessary.

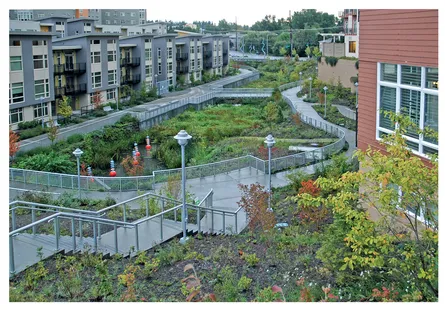

Using information emerging from urban ecology and ecosystem research, planners and designers can fashion a set of policies and practices that embed both ecocentric and anthropocentric values into green infrastructure systems at various scales. As a systematic, holistic approach, involving transdisciplinary cooperation, green infra structure addresses pollution, habitat, recreation, open space and urban form (Figure 1.2).

In addition to the erosion of habitat and subsequent loss of biodiversity, municipal governments are increasingly unable to provide the amenities and services sought by citizens within the political and budget constraints of single-use solutions. We must also adapt to changes in the global climate that will disrupt our food and energy systems and impact natural ecosystems in unpredictable ways.

We need effective and efficient solutions to these problems and others. Furthermore, the solutions should not generate other future problems. In fact, we want solutions that improve the quality of our lives, through better living, working and recreation environments.

Figure 1.2 Restoration of creeks, the creation of constructed wetlands for pollution reduction and high-density mixed-use development can be combined, as at Thornton Creek in Seattle, Washington.

The need to address many problems simultaneously is what makes green infra structure cost-effective and efficient. A comprehensive network of linear parks, open spaces and habitat patches can structure our neighborhoods and save threatened species. It can remove the pollutants from road runoff and feature inspiring trails through naturalistic landscapes. It can conceal our electrical and data lines below urban agriculture. It can assure the purity of our drinking water, serve as educational resources for our schools and entice new business and residents to locate in our towns and cities.

This book challenges municipalities to reformulate their policies for trails, parkland, stormwater management, wildlife habitat and other green infrastructure components. Green infrastructure won’t significantly mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, but it can help us adapt to the changes we can no longer avoid.

Definitions and themes

“Green infrastructure” is a term that is evolving in its meaning. We are familiar with the infrastructure of transportation (highways, bridges, traffic signals, automobiles, petroleum refineries, etc.), potable water (wells, reservoirs, water mains, etc.), sewage treatment, communications (telephone, data, television, radio, internet) and energy generation (hydroelectric dams, transmission lines, transformers, etc.). These foundational systems of urban life are sometimes called gray infrastructure. Even a quick consideration reveals that these systems are important to human health and wellbeing, particularly if the regional food system is also considered to have infrastructure components. This book defines infrastructure as a system of components connected by a network, just as are the transport, communication and electric networks.

There are, of course, networks in nature. Rivers, streams, lakes and oceans compose a natural infrastructure that supports ecological functions. For many plants and animals access to this infrastructure is necessary for survival. It is easy to construct other spatial, energy, material and movement networks, in our imagination, when considering the needs of plants and animals.

As a continuous network of corridors and spaces, planned and managed to sustain healthy ecosystem functions, green infrastructure generates pollution mitigation, recreation, economic value, urban structure, scenic and other human benefits. The context of green infrastructure is suburban and urban, but optimally connects to wild nature and fully functioning ecosystems.

Green infrastructure is a phrase sometimes used to mean the conversion of a gray infrastructure element to a more renewable or sustainable one. For example, photovoltaic generation of electricity is sometimes suggested as a green infrastructure option since it reduces the need for finite fossil fuel. However, that definition is far too narrow to capture the concept advanced by this book. Site scale elements, however environmentally beneficial, are not considered part of the green infrastructure if they are geographically isolated from a network of open-space corridors and spaces. This distinction emphasizes that connectivity between spaces large enough to support ecosystem functions and human use is a critical characteristic. Multiple functions are other key aspects of the definition. Single-purpose solutions, such as stormwater detention ponds, are impoverished green infrastructure components even if they were connected to the network, unless additional benefits of recreation, habitat, water quality improvement and aesthetics are added to them. These secondary benefits increase cost-effectiveness and efficiency through multiple use and compact organization.

In summary, this book will develop the following themes:

- the benefits of green infrastructure as a planning and conservation tool;

- the requirements of ...