This is a test

- 102 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The aim of this text is to promote an understanding of dyspraxia and movement development among professionals who work with children, and also to offer a text which is accessible to parents. It presents a cognitive processing model of dyspraxia from a developmental perspective, and addresses issues of social development in addition to the more easily observable motor planning difficulties which are associated with dyspraxia. The difficulties which may face the dyspraxic child at home and at school are described with strategies for managing their difficulties. Details are provided of the support services available and how they may be accessed.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dyspraxia by Kate Ripley,Bob Daines,Jenny Barrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

What is Dyspraxia?

Praxis is a Greek word which is used to describe the learned ability to plan and to carry out sequences of coordinated movements in order to achieve an objective.

Dys is the Greek prefix ‘bad’ so dyspraxia literally means bad praxis.

A child with difficulties in learning skills such as eating with a spoon, speaking clearly, doing up buttons, riding on a bike or handwriting may be described as dyspraxic. The movements which are involved in these activities are all skilled movements which are voluntary and may be affected by dyspraxia. Voluntary movements, unlike reflexes, are under the conscious control of the individual who carries them out.

Developmental dyspraxia is found in children who have no clear neurological disease. This book is about movement problems in children which are complex and involve various poorly understood aspects of how the body and the brain work.

Box 1.1

A formal definition of dyspraxia by a neurologist:

A disorder of the higher cortical processes involved in the planning and execution of learned, volitional, purposeful movements in the presence of normal reflexes, power, tone, coordination and sensation (Miller 1986).

Some researchers (Dawdy 1981) describe children with developmental dyspraxia as showing impaired performance of skilled movements despite abilities within the average range and no significant findings on standard neurological examination. Other researchers have identified links with learning, language, visual-perceptual and behavioural problems (Henderson and Sugden 1992). It is important to remember that all children are different and that some difficulties may not become apparent until specific demands are made, such as learning to use a pencil. A difficulty becomes significant when it interferes with the way that a child is able to carry out the normal range of activities which is expected at his or her age: the usual developmental goals.

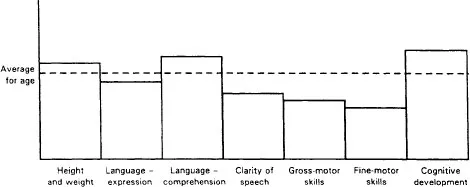

Figure 1.1 A developmental profile

The idea of a developmental profile may be helpful when considering a child who has difficulties with coordinated movements (see Fig. 1.1). If motor skills are at a different level from the other areas of development, there may be a specific problem such as developmental dyspraxia.

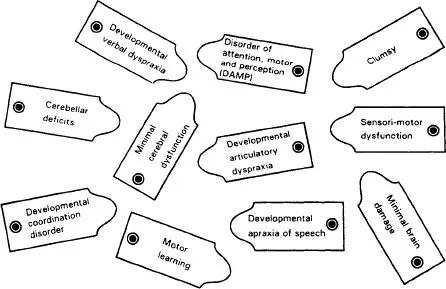

The term dyspraxia is used differently by professionals within and across occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, psychology and medicine. There is also a range of other labels which may be used to describe developmental dyspraxia but they have no clear definition (see Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Labels that are used to describe development dyspraxia

In this book we have used the term developmental dyspraxia to refer to difficulties associated with a vital area of development in children, the development of coordination and the organisation of movement. That is, problems with

Getting our bodies to do what we want when we want them to do it.

How praxis develops

Praxis is learned behaviour but it also has a biological component. The sequence of motor development is pre-determined by innate biological factors that occur across all social, cultural, ethnic and racial boundaries (Gallahue 1982). The development of movement abilities is an extensive process which begins with the earliest reflex movements. The developmental schedule for voluntary movements unfolds between the ages of two and twelve years when an adult level of competence is possible. According to Luria, a famous Russian neurologist, the area of the brain which is responsible for simple voluntary movement, e.g. hammering a peg into a hole, is developed on average by four years of age. By six to seven years the area of the brain which is needed for more complex movement combinations is developed. Children with difficulties continue to make more movement errors and action errors than other children of the same age.

The sequence of motor development can, however, only become operational by continual interaction with the external environment. The learning of early movement skills usually takes place in the context of play.

The early learning of movement patterns

Box 1.2

One of the early toys that most babies have is the rattle that parents attach to the pram. A baby will respond to this novelty by showing general excitement which involves random movements of his arms and legs and even the whole body. The movement itself will cause the toy to vibrate and make a noise which in turn stimulates more interest in the toy. An accidental contact with the toy, as a result of the excited movements, will give pleasurable feedback in terms of noise and movement of the toy. In a relatively short time most babies learn how to strike the toy deliberately in order to get it to move and to make a noise. The action of the baby becomes more skilled over time so that one arm, rather than all four limbs, will be involved and it will be used with an increasing degree of control over the force, direction, distance and amplitude of the movement. The baby’s movements become better coordinated and more efficient as they become more skilled.

Parents carefully record and even video the motor milestones which their baby achieves but the complexities of the learning of the coordinated movements of muscle groups which are required in order to raise the head, to roll over, to sit up, to stand and to walk are lost to most memories. As we watch babies and young children we are aware that a great deal of practice is needed in order to ensure the smooth performance of these skills which come under automatic control for most people at an early age. As older children and adults we don’t consciously have to plan how to move our bodies in order to stand up or scratch our nose – we just ‘do’ it. Learning to drive may be the only time when adults are faced with the complexities of learning a new skill which demands the coordinated action of different parts of the body together with the fine tuning of the force, amplitude and timing of a sequence of movements.

Children with developmental dyspraxia have difficulties acquiring both the early motor skills and learning new, more complex skills. They may, with more practice than others of their age, reach a reasonable level of competence for a specific skill such as placing the pieces in a favourite tray jigsaw, but this skill will not necessarily generalise to other related skills.

Where things might go wrong

Organised physical movement is dependent upon the sensory information which the body receives from its environment. Some sensors operate very early in life, possibly even before birth. The sensors that are important for movement are the:

• tactile receptors;

• vestibular apparatus;

• proprioceptive system.

People are seldom consciously aware of the roles of the vestibular apparatus or the proprioceptive system although information from the tactile receptors may impinge on consciousness as when we tread on a drawing pin. We are more consciously aware of processing the information which we receive from the senses of taste, smell, sound and vision. One theory about dyspraxia (Ayres 1972) gives central importance to the ability to integrate the information which is received from the senses. If this is disrupted the ability to plan and to execute skilled or novel (new) motor tasks may be impaired.

Box 1.3 Tactile receptors

The tactile receptors are cells in the skin that send information to the brain about light, touch, pain, temperature and pressure.

Box 1.4 Vestibular apparatus

The vestibular receptors are found in the inner ear. The vestibular sense responds to body movement in space and changes in head position. It automatically coordinates the movements of eyes, head and body, is important in maintaining muscle control, coordinating the movements of the two sides of the body and maintaining an upright position relative to gravity.

Box 1.5 Proprioceptive system

The proprioceptors are present in the muscles and joints of the body and give us an awareness of body position. They enable us to guide arm or leg movements without having to monitor every action visually. Thus, proprioception enables us to do familiar actions such as fastening buttons without looking. When proprioception is working efficiently, adjustments are made continually to maintain posture and balance and to adjust to the environment, for example when walking over uneven ground.

Most researchers (Cermak 1985, Conrad et al. 1983) emphasise two elements in developmental dyspraxia:

• ideational or planning dyspraxia;

• ideo-motor or executive dyspraxia.

Dewey and Kaplan (1992) identified three groups of children: Group 1 showed problems in both areas, Group 2 difficulties with the execution of movement patterns and Group 3 difficulties with the planning of sequences of movements.

Conrad et al. (1983) divided the individuals with ideational or planning dyspraxia into those who had difficulties with the planning of sequences of movement and those who had difficulties with moving themselves or objects in two- or three-dimensional space. The latter involves spatial awareness and directional awareness which can present additional problems for some dyspraxic children.

It is probable that all three elements: sensory integration, the planning of action and the execution of the plan, are involved in the efficient carry...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- 1 What is Dyspraxia?

- 2 Dyspraxia: a Developmental Perspective

- 3 The Assessment of Dyspraxia

- 4 The Development of Voluntary Movement and How to Help

- 5 Living with Dyspraxia

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Useful addresses

- References

- Index