eBook - ePub

Late Quaternary Environmental Change

Physical and Human Perspectives

This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Late Quaternary Environmental Change addresses the interaction between human agency and other environmental factors in the landscapes, particularly of the temperate zone.

Taking an ecological approach, the authors cover the last 20, 000 years during which the climate has shifted from arctic severity to the conditions of the present interglacial environment.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Late Quaternary Environmental Change by Martin Bell, M.J.C. Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 Environmental change and human activity

Introduction

Twenty-five thousand years ago the world was in the grip of the last ice age. The 14 ka1 which followed saw some of the most dramatic climate changes in the recent history of the earth. Documentation of the rapid nature of some of those changes is one of the great achievements of Quaternary science, and the evidence makes a persuasive case for the relevance of research on past environments to contemporary environmental concerns such as global warming. The climatic shift from a regime of arctic severity to one of relative warmth that began around 15 ka BP led to the virtual disappearance of the continental ice sheets, to contraction of the mountain glaciers, and to the replacement of barren tundra by mixed woodland over large areas of Europe and North America. Meltwater from the wasting ice sheets raised global sea level by over 120 m, while a combination of climatic and vegetational changes exerted a major influence on a range of other environmental processes such as weathering rates, soil formation and the activity of rivers.

The end of the last ice age at 11.5 ka BP was rapidly followed by the earliest agriculture and then by the first large settlements and increasingly complex societies. In some areas, human activity had significant environmental effects even early in the post-glacial, but with the transition from hunter-gatherers to sedentary agriculturalists, to urban and then to industrial communities, people have had an increasingly profound effect on landscape. Indeed, over the last five millennia, anthropogenic activity in the temperate midlatitude zones has become almost as important as natural agencies in determining the direction and nature of environmental change. Moreover, with the increased burning of fossil fuels and other forms of atmospheric pollution, human activity may be beginning to dictate the course of future climate changes for the first time in the history of the earth.

Landscape, people and climate are three variables which are inextricably linked (Figure 1.1), and an understanding of the course of recent environmental change requires an analysis not only of the elements themselves, but also of the way each influences the other in the broader context of earth systems science. The purpose of this book is to examine the interactions between people and the natural environment against a background of climate change. This reflects an increasing recognition by scientists and politicians alike of the importance of integrating scientific and social perspectives. Together they enable us to understand how natural environments have been transformed as human landscapes. It is also increasingly recognised that this integrated perspective is an essential part of planning for a sustainable future. The main focus of the book is on the northern temperate zone of Europe and North America where the effects of environmental change have been particularly marked and where the evidence for both natural and anthropogenic past processes is especially well preserved. Examples are also drawn from other geographical areas, however, where these help to illustrate the diversity of past people–environment relationships.

The book also seeks to draw on and integrate the differing academic traditions in the study of

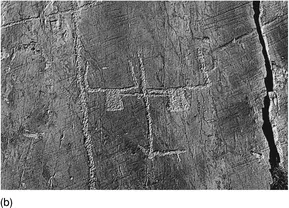

Figure 1.1 The Merveilles Valley in the high Alps of Mont Bégo on the French–Italian border: (a) glacially striated rock surfaces where Bronze Age communities have pecked art showing weapons and animals; (b) a plough scene (Barfield and Chippindale, 1997). This landscape was made cultural by human agency, and we may speculate that seasonal pastoralists in the high Alps attached particular significance to this dramatic landscape, or the route across the Alps on which the art lies (photos Martin Bell)

environmentally focused archaeological science: from North America, anthropological and earth science perspectives; from Scandinavia, ethnohistoric approaches to cultural landscape; and from Britain and western Europe, environmental archaeology and new social and perceptual dimensions.

The time frame of the book covers the transition from the last cold stage in the Northern Hemisphere (Late Weichselian in Europe; Late Devensian in Britain; Late Wisconsinan in North America), to the present warm episode (interglacial) which began around 11.5 ka BP (Holocene in Europe and North America; Flandrian / Postglacial in Britain). The database is broad ranging, drawing on material from geology, geomorphology, geography, biology, archaeology, anthropology, history and social theory. However, the approach to the material is firmly rooted in geography and archaeology, in that the emphasis throughout is on landscape as the home for the human race. In this introduction many of the key concepts and terms (in bold) are introduced and defined and, in particular, we consider the integration of the social and scientific perspectives.

Earth science, geography and archaeology

The relationship between earth science, including physical geography, and archaeology has been long standing and productive. Discovery in ancient sedimentary contexts, such as caves and river gravels, of human bones and stone tools accompanying the bones of extinct animals led, in the mid-nineteenth century, to recognition of the antiquity of humanity (Grayson, 1986). In this way the foundations were laid both for Darwinian evolution and the development of archaeology as an academic discipline. Archaeological sites and finds are preserved within sediments, so that a full contextual understanding generally requires the application of geological, pedological or geomorphological approaches. This has led to the development of geoarchaeology: archaeological research which draws on the methods, techniques and concepts of the earth sciences, and which has been a particularly influential strand of archaeological science in North America (Herz and Garrison, 1998; Rapp and Hill, 1998), where many archaeological sites are stratified in riverine sedimentary contexts. Earth science approaches are becoming increasingly important in north-west Europe (Brown, 1997), the Mediterranean and South-west Asia (French, 2003; Wilkinson, 2003) and in other areas of the world as well.

The disciplines of geography and archaeology have much in common, being concerned respectively with the spatial and temporal dimensions of the human condition. The prime concern of

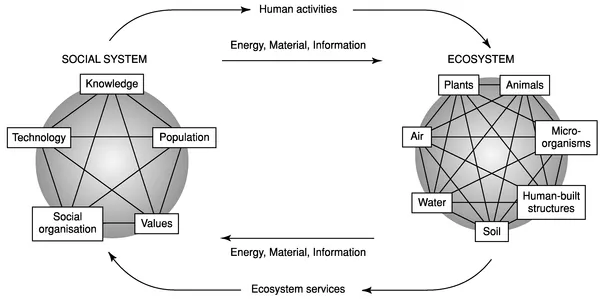

Figure 1.2 The interactive relationship between an ecosystem and a human social system (after Marten, 2001)

geography is to understand the processes that operate within the natural environment (physical geography) and to evaluate the ways in which people interact both with their environment and with each other (human geography). Archaeology deals with those aspects of the human past which are mainly elucidated using material remains (including environmental evidence) rather than written sources. Both physical geography and archaeology have been profoundly influenced by the science of ecology, which is concerned with the interactive relationship of organisms to each other and to their environment.

The components of an ecosystem (a living community and its environment) and its relationship to a human social system are shown in Figure 1.2. This includes two-way exchanges of energy, materials and information and the interactive effects of each factor on others. The diagram also includes the notion of ecosystem services, those commodities and benefits that the environment provides for people (Daily, 1997). This concept, recently developed in the USA, aims to quantify the full range of benefits which may be secured by environmental relationships which are sustainable, i.e. meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Marten, 2001). Each of the various elements (climate, geology, soils, flora, fauna, disease and people) are interlinked so that impact on one factor can have repercussions throughout the system, including a feedback effect on the original factor (Butzer, 1982).

Ecological concepts have been highly influential in the development of the subdiscipline of environmental archaeology: the study of the ecological relationships of past human communities, and the interactions between people and environment through time (Evans and O'Connor, 1999). Palaeoecological investigation using biological evidence has been a major aspect of archaeological science in north-west Europe, particularly Denmark (Kristiansen, 2002) and Britain, for more than a century, and is an approach that is increasingly being adopted in the Americas (Reitz et al., 1996; Dincauze, 2000).

Not only does archaeology benefit from these relationships with earth and biological science but the benefits are reciprocal. Archaeological sites preserve dated contexts containing information about past environments, and these help to provide a past dimension (time-depth) for studies of environmental processes. Such contexts also contain evidence of the interaction between past human communities and the environment, the effect that people have had on their environment through time and the spectrum of environmental relationships experienced by societies, including those very different from our own. In this way the core mission of archaeology can be seen as complementary to anthropology, the science of people (Gosden, 1999). Both explore the diversity and richness of human existence.

It is increasingly recognised that there are few truly natural environments (i.e. those unaffected by humans). People have contributed to the present condition of most of the world's environment types, even in some of the most remote areas such as Pacific islands and tropical rainforest long considered pristine. In most areas of the world, what we see, what environmental scientists analyse and what conservationists seek to preserve is, to varying degrees, a human creation. For this essential reason an understanding of past human activity should often be part of effective conservation strategies (Chapter 8).

Landscapes are a product of the interaction between humans and environment which creates distinctive mosaics on varying scales reflecting particular ways of life, such as agricultural systems (Crumley, 1994). Landforms, soils, plants and animals have been modified by people who, in many areas, have also created a socially constructed landscape marked by particular arrangements of sacred places, wild places, settlements, fields, tracks, tombs, woodland, etc. This is the concept of the cultural landscape, an approach pioneered most notably in Scandinavia, where there has been a close relationship between ethnohistorical research (work on historically attested folk practice) and palaeoenvironmental science (Birks et al., 1988; Berglund, 1991). By definition, therefore, landscapes are the product of human agency. Furthermore, environments do not have a neutral and independent existence, they exist in relation to organisms whose environments they are (Ingold, 1986, 1990, 2000). The materials which people use have physical properties, which make them useful, and they also possess attributed social significance (e.g. high or low status, female associations, magical properties). The heathland plant gorse, or furze (Ulex europaeus), illustrates the point (Evans, 1999: 105). It has a practical value as fuel, animal fodder, etc., but its gathering from the heath would also have played a part in articulating gender and social roles because the ethnohistorical record shows that particular groups were responsible for this activity.

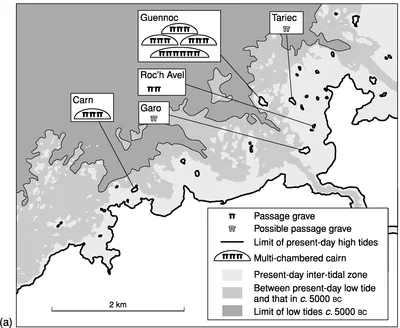

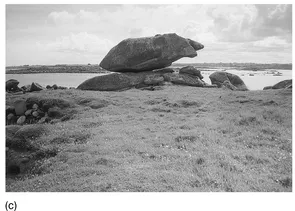

Physical properties and social significance together contribute to the economic role that things play and thus to the articulation of social relationships. A place may be attractive for the resources it offers and the food-gathering opportunities it affords, because of the symbolism attached to striking forms of rock exposure (Bradley, 2000b), their colours (Cummings, 2000) or a combination of factors. These approaches draw, for instance, on phenomenology, i.e. the way in which landscapes were encountered and perceived (Tilley, 1994). Breton tomb locations (Figure 1.3) demonstrate the interrelationships between these perspectives; the example shown is a very rich and diverse coastal estuarine environment, tombs were located on what, in the time of lower Neolithic sea level, were rocky rises, or in the case of Guennoc an island. Rocky landforms are likely to have contributed to the significance of place and tomb passages are oriented on landscape features (Scarre, 2002). Such considerations highlight the need for an interdisciplinary approach, integrating environmental science and social perspectives thereby combining a landscape ecological approach (Forman, 1995) and phenomenology.

Increasingly, cross-fertilisation is taking place between those concerned with environmental and social perspectives (e.g. Edwards and Sadler, 1999; Evans, 2003). Simple explanations of the impact of environmental change on people, and of people on environment, are often not adequate. There is a need to move from an emphasis on the false dichotomy of people versus nature to a more integrated perspective. This may, for example, involve communities and their environments in a process of coevolution, in which interactive relationships have mutual influence (Rindos, 1989; Redman, 1999). Such an approach has proved particularly valuable in developing a better understanding of agricultural origins (p. 151).

Figure 1.3 Aber Benoit, Brittany, France: (a) the locations of Neolithic tombs on what at a time of lower sea level were rocky rises or islands above a now drowned coastal plain, some tombs show evidence of orientation on topographic features (after Scarre, 2002, Figure 6.6); (b) one of the four tombs on the small island of Î...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to Second Edition

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Environmental change and human activity

- 2 Evidence for environmental change

- 3 Natural environmental change

- 4 Consequences of climatic change

- 5 People in a world of constant change

- 6 Cultural landscapes, human agency and environmental change

- 7 People, climate and erosion

- 8 The role of the past in a sustainable future: environment and heritage conservation

- 9 The impact of people on climate

- Bibliography

- Index