![]()

Part I

BoP vision and capability

The importance of purpose and culture

![]()

1

The importance of vision and purpose for BoP business development

Urs Jäger

INCAE Business School, Costa Rica and Nicaragua

Vijay Sathe

Peter F. Drucker and Masatoshi Ito Graduate School of Management, USA

Ever since the work of Prahalad and Hart opened business eyes and minds to the opportunities offered by the world’s four billion poor people who live on less than five dollars a day, there has been a corporate awakening and quite a few initiatives to access the base of the pyramid (BoP) space. We first describe some of these efforts to gain a deeper appreciation of the circumstances that led to success and failure. We then turn to the question of what your company’s vision for this BoP space is, and what it should be.

It is both costly and difficult to succeed in the BoP space, so why should a company’s vision include this space? One reason is that the purpose of the enterprise compels or at least suggests that the company should have a successful BoP business. Another reason is the Vision 2050 report, which points to the increasing importance of the BoP market. A third reason is leadership that believes in what Peter Drucker wrote many years ago, that every social problem is a business opportunity in disguise.

Even if a company wants to operate in the BoP space for these and other reasons, both ambition and capability are required to succeed. Purpose, together with ambition and capability, then determines what a company’s BoP vision currently is, and what it should be.

1.1 Corporate awakening in accessing the BoP space

Ever since the work of Prahalad and Hart opened many eyes and minds to the opportunities offered by the world’s four billion poor people who live on less than five dollars a day (Prahalad and Hart 2002), more and more companies have attempted to access the “BoP space”. We use the term “BoP space” to refer to the complex and dynamic web of resources (tangible and intangible), rules (formal and informal) and relationships (economic, environmental, political and social) that companies doing business at the base of the pyramid (BoP) must learn to navigate if they are to be successful. In this chapter we examine how a variety of companies have attempted to do business in the BoP space, and what everyone can learn from their experience.

For instance, Khanna and Palepu (2006) show how “emerging giants” from developing countries, companies such as Tata in India and LG in Korea, have successfully accessed BoP markets based on their intimate understanding of the BoP space. Examples of other emerging giants are the Mexican company Cemex, Chile-based ENAP (Empresa Nacional de Petróleos), PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela SA) from Venezuela, and Petrobras from Brazil. While in 1990 the Fortune 500 rankings listed only a few companies from emerging countries, the number had already reached 52 by 2006.

Multinational companies from the developed world are also entering the BoP space. Companies such as Tetra, Puma, Danone, Coca-Cola, Nestlé and Walmart have invested millions of dollars in initiatives to explore new market opportunities in the BoP space with some success. For example, Starbucks and Nespresso have profitably integrated BoP coffee producers into their supply chains and such sourcing has become a common business practice, particularly in Europe and the United States. Fairtrade, a European non-governmental organization (NGO), reports a 52% increase in its certified coffee producer organizations worldwide between 2002 and 2011, representing more than half a million small farmers in rural areas across 28 countries.

These new business realities of emerging giants, multinationals and other companies, some of which are quite small, also find expression in new concepts to describe “doing business in the BoP space” such as social business, creating shared value, corporate social responsibility, impact investing, social entrepreneurship and social enterprise. However, despite the growing interest in doing business in the BoP space, there are still far too few examples of enterprises that have created a successful BoP business. Why?

1.2 Reasons for lack of success

Two recent studies provide insight into why so many attempts to access the BoP space have failed; each offers helpful pointers on what is needed to create a successful BoP business.

Garrett and Karnani (2010) analysed three well-known BoP ventures by multinational companies. In 2005, Essilor teamed up with two Indian not-for-profit eye hospitals to launch a BoP venture to provide inexpensive eyeglasses for India’s millions of rural poor. After a few failed attempts, in 2000 Procter & Gamble launched PuR, a powder that, when mixed with water, produced clean drinking water. In 2006, Danone teamed up with Grameen Bank, the pioneering microfinance organization in Bangladesh, to create Grameen Danone, with the mission of developing a yoghurt product specifically designed to alleviate child malnutrition in Bangladesh. Procter & Gamble and Danone have failed to generate profits so far. Essilor’s initiative has become profitable, but it remains marginal in terms of size and growth.

Garrett and Karnani (2010) identify four traps that one or more of these ventures fell into that led to disappointing results. The first trap is to assume that unmet needs constitute a market. For example, it is easy to estimate how many millions of Indians need eyeglasses but it is far more difficult to know how many of them can afford to buy eyeglasses at various price points. The second related trap is to assume BoP customers can afford even drastically reduced prices, even for desirable Western products that are specifically redesigned for BoP markets. The third trap is to underestimate the cost and difficulty of reaching BoP customers, and the fourth is to focus on so many BoP objectives that the project loses its focus.

Garrett and Karnani (2010) offer two basic recommendations for success in the BoP space: (1) reduce product cost and increase affordability via technological innovation, as was accomplished in the case of mobile phones in India; and (2) more controversially, reduce quality to a level that is acceptable to and affordable by BoP customers, as in the case of Nirma detergent that blisters poor hands that cannot afford a gentler but more expensive alternative. Their overriding conclusion is that success in the BoP space requires the same strategic and executive discipline as success in any other business space requires: focused objectives, understanding the customers, and appreciating the role of economies of scope and scale to bring price points down to levels that make the value proposition attractive and affordable to the poor.

Drawing on a larger database of more current experience, Simanis (2012) reaches the same basic conclusion: higher production, distribution and marketing costs, as well as a higher cost of capital (30%) than is paid by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs (20%), make it very difficult and expensive to reach BoP customers, and success requires that good intentions be grounded in hard-headed business fundamentals.

Simanis goes further to identify the conditions under which it may be possible to lower BoP costs and increase BoP volumes to the levels needed for a successful BoP business: ability to reduce production and distribution costs by being able to leverage the existing infrastructure; lower costs to educate customers because they are already familiar with the product. Unilever could do both to enable its Wheel detergent to successfully take on BoP market leader Nimra. Simanis also challenges the conventional wisdom that business solutions for the BoP space must be based on a low-price, high-volume business model by showing that a higher-price, lower-volume model can generate the required level of profits by bundling and localizing products, offering an enabling service and cultivating customer peer groups.

But Simanis does not address the concern that some people may perceive high-price, high-margin products and services sold to the poor as exploitation of the poor. In fact, the question of whether even well-intentioned BoP ventures are actually good for the poor is not adequately addressed in the BoP literature. Two points are worth noting: First, companies might assume that customers from the BoP space will buy their products and services only if they meet their needs. “Doing good” or having impact is thus measured according to an economic logic: the more a company sells, the higher its contribution to the BoP. But second, given the conditions of life in the BoP space, what is good for the individual may not be good for the community as a whole. However, it is not easy to measure the impact of products and services on the BoP space. Articles such as Herman Leonard’s “When is doing business with the poor good—for the poor?” (2007) provide an introduction to the highly complex field of social impact assessment. Methods for measuring these impacts are urgently needed in light of one of Peter Drucker’s famous injunctions: To manage, one must be able to measure (Drucker 1973: 400).

The conclusions of both Garrett and Karnani (2010) and Simanis (2012) emphasize the importance of getting back to the basics: success in the BoP space requires business models and strategies that are appropriate for this market. But a more fundamental question that is rarely asked in the BoP literature is: since doing business at the base of the pyramid is so costly and difficult, why bother with it? It is important for company leaders to ask this question seriously and answer it honestly in order to decide whether their company should even have a BoP business. If the purpose of the enterprise compels or at least suggests that it should have a BoP business, what is the right model for it?

1.3 What is the right model for a BoP business?

The classic distinction between for-profits and non-profits is no longer adequate to describe the purpose of the enterprise. The former are engaged in activities that were previously the province of non-profits, and the latter are doing business to fund their operations. What then is the right business model for enterprises doing business in the BoP space?

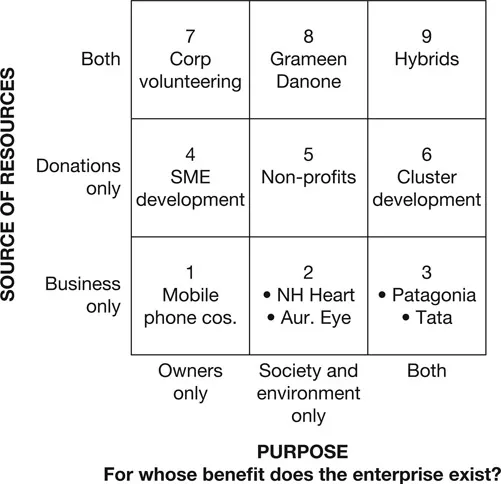

Figure 1.1 provides a taxonomy to answer this question. The horizontal axis represents the purpose of the enterprise. For whose benefit does the enterprise exist—its owners only, society and environment only, or both? The answer of course depends on the legal structure of the enterprise and its charter, but it is also important to determine for whose benefit the enterprise exists in practice. How this can be done is explained shortly. The vertical axis represents the source of funding for the operation of the enterprise—is it from business activities only, from donations of financial and non-financial resources (houses, cars, services or the time of volunteers) only, or both? Each cell in Figure 1.1 represents a business model. Let us briefly examine each one.

Figure 1.1 Map your enterprise on its purpose and the source of its resources

Cell 1. These are classic shareholder or privately owned companies. But as the example of mobile phone companies in India shows, these for-profits can produce social and environmental benefits that match or even exceed those of the nonprofits whose explicit purpose is to realize such benefits. This applies above all to BoP spaces where the creation of jobs providing regular income and social stability have high social value.

Cell 2. These are social enterprises that generate all the resources they need through their business activities and do not rely on donations. The Narayana Hrudayalaya heart hospital and the Aravind eye hospital, both in India, are world-famous examples of this type of enterprise. Both create high social value by their relatively cheap health services and fund their operations by selling those services at a very low price to the poor and a higher—but still affordable price—to the middle- and upper-class people.

Cell 3. These organizations are similar to the ones in Cell 2, but both the owners and society/environment are the intended beneficiaries. We will examine Patagonia shortly, but first consider India’s Tata Group. As a senior executive of this company recently told The Economist (2009), “Return on capital is not at the centre of our business. Our purpose is nation-building, employment and acquiring technical skills.”

Cell 4. Examples are enterprises that depend on donations to facilitate economic development by promoting business entrepreneurship and ownership and better management of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Cell 5. These are non-profits such as World Vision, which are financed by donations only and exist for the benefit of society or the environment.

Cell 6. Examples are enterprises that depend on donations to promote cluster development. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank and other donors support the economic development of areas (such as all of Costa Rica) and invest in companies as well as institutions designed to promote foreign investment.

Cell 7. Corporate volunteering is in vogue. Companies permit or encourage employees to work for a social or environmental cause chosen by the company or by themselves, with time either paid by the company or volunteered by the employee. The purpose of these efforts is employee growth and development as well as reputational benefits for the company from its corporate social responsibility initiatives.

Cell 8. This represents an enterprise that exists for the benefit of society and the environment and relies on revenues from its business activities as well as on donations to fund its operations. Professor Yunus, Grameen’s founder, called the Grameen Danone venture a “social business” and he would probably place it in Cell 2, but since it promises to return only the principal to the shareholders and no interest or dividends on the amount invested, the investors are in fact donating the cost of capital.

Cell 9. Hybrids are combinations of for-profit and non-profit enterprises. For example, a non-profit museum with a for-profit gift shop is a hybrid.

The business models in Figure 1.1 may qualify for legal protection a...