As I walked through the village in the Maasai Mara National Reserve asking questions about traditional education for his people, my host stressed the importance the community placed on their children. The Maasai people are regarded as Africa’s greatest warriors. They live in circular villages in the savanna, using their famed swords to protect their families and livestock from lions. For generations, their traditional greeting has reflected their core values. One Maasai meeting another, whether the strongest and fiercest warrior or the eldest grandmother, would ask, “Kasserian Ingera?” which translates to “How are the children?” The traditional and hoped-for response is, “All the children are well.” The Maasai understand that societal health is dependent upon the wellbeing of all the children.

All of our children are not well. In our global society, too many of our children are living in poverty. Too many of our children do not have access to food or clean drinking water. Too many of our children are living with the consequences of conflict and war. While many organizations and individuals are working to ensure the health of our next generation, collectively, we have prioritized other goals and have put our future in jeopardy. Many of our children are not well because we have been more focused in our education systems on what is easily quantified rather than what is most important. We have lost sight of what our children need to be happy, healthy, and contributing citizens to the global society they will inherit from us.

Education is one of the most fundamental human acts. From the time that humans developed the capacity to communicate, older generations have passed knowledge on to their successors, carefully sharing the most important aspects of who we are. Our ability to feel and empathize defines us as a species, and it is no coincidence that the part of our brain that evolved to control memory is also responsible for supporting our emotions.1 Because teachers represent the most important relationship to students in schools, and human relationships are essential to learning, the excellence of our education system will never reach beyond the caliber of the educators within it. Outstanding education systems are filled with outstanding schools. Outstanding schools are made so because they are filled with outstanding teachers.

The backbone of our society is education. All around the globe from the most affluent cities to the most isolated rural villages, schools are the center of the community. Societal health is dependent upon our ability to pass skills necessary for survival to our future generations. Each community has different educational needs and challenges that must be addressed, but every society’s success is dependent upon its ability to maintain an educated populace over time. Our future hinges on the learning and wellbeing of our children.

The New World of Learning

We are now entering an unprecedented time in human history. Increasing computer power along with nearly ubiquitous Internet connectivity will change the way humans live, work, interact and relate to each other. As we mentioned in the Introduction, Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, describes this period of expansive digitization and automation as “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.” As Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning, the “Internet of Things,” biotechnological advances, and nanotechnology turn the most imaginative science fiction into reality, we will be forced to continually reevaluate the question, “What does it mean to be human?”

This increased digitization and automation have significantly impacted education in recent years. Content delivery is increasingly accessed online. The Khan Academy was started in 2004 when Salmon Khan started recording tutorial videos for his cousins and posting them on the Internet. As others discovered the benefits of learning through online videos, Khan developed more content to meet the demand. The nonprofit service has expanded to become the flag bearer for online educational content with more than 40 million students and 2 million teachers using the website every month. Anyone wishing to learn about a topic can probably find dozens of relevant videos on YouTube. In 2016, 58 million people took Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) offered by over 700 different universities.2 Knowledge is more easily available, cheaper to access, and more easily curated than ever before in human history.

At the same time, the importance of understanding how knowledge in different disciplines connects, understanding the applications of knowledge to solve complex problems and grasping the ethical implications of those applications is more valuable than ever before. As the Internet age made information ubiquitous, the workforce began to transition toward a focus on “21st Century Skills” such as critical thinking, creativity, communication and the ability to collaborate with others. Now, in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, a further transition is taking place. As the communication between computers and AI increases, information will be shared without humans. That digital transfer of information between devices, combined with advances in the capabilities of AI, will lead to the automation of any job that can be represented by a series of algorithms. We’ve already seen this trend start to take place.

In 1996, someone hired to drive a truck of goods from farmland to the city would have needed to be very knowledgeable about the roads he or she would have to drive. If a road was unexpectedly closed, a new route would have to be used. Drivers who knew the geography of their area well were able to reroute without taking time to stop their truck to look at paper maps. This saved time and money.

By 2006, GPS systems and crowdsourced traffic mapping by Waze, an app for mobile devices, made paper maps obsolete. Truck drivers no longer needed to be geography experts to efficiently navigate around obstacles. Ten years later in 2016, self-driving Uber cars began driving passengers around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Within a decade, it is very possible that truck drivers will cease to exist. The trucks, loaded by machines rather than humans, will drive themselves.

An education system that does not address this trend is irrelevant. An education system unable to adapt to the speed of innovation in society is obsolete. An education system that is not preparing citizens to be happy and healthy in the world they will live is worthless.

I graduated university and started teaching in 1997, 20 years before this book was written and just a few years after the World Wide Web began to be widely used. My first experience with the Internet was accessing information using the University of Minnesota’s Gopher Protocol, a precursor to the Internet we know today. Being able to send an email or access a weather report on a monochrome screen seemed groundbreaking at the time. I didn’t even mind walking a kilometer across the university campus or waiting my turn to use one of the shared computers in the library. At that time, research was still mostly done by looking at old journal articles on microfilm or micro-fiche. It was both difficult to find relevant information and extremely time consuming.

In my wildest dreams, I could not have imagined what teaching would be like now, when the entirety of human knowledge is accessible through a device in my pocket. I regularly have live video conversations with people around the globe. Tools like Skype Translator and Google Pixel Buds make it possible to have those conversations with those who do not even speak the same language. With Moore’s Law telling us that processing power doubles every 18 months and with quantum computing on the horizon, it is clear that the changes in the last third of my career will be far greater than those in my first 20 years.

The same technology that is changing my job as a teacher is giving my students the opportunity to become empowered problem solvers. They collaborate with children across the planet on projects to overcome inequities they identify. In the past 4 years, they have interviewed scientists in Antarctica, learned from astronauts on the International Space Station, and collaborated with people in over 90 countries. Each connection allows them to share a little of our community and themselves with the world and to internalize transformational experiences that only come with being exposed to different cultures. My students have read books on natural resources to Ukrainian kids, discussed gender equity in STEM careers with peers in Tunisia and partnered with classes around the globe to tackle some of the world’s biggest problems.

Each new exciting learning experience that is available to my students brings with it new questions. Am I preparing them for the future they will face? Am I giving them the skills they need to face the problems with which our generation is leaving them? How do I continue to meet the demands of my job and also stay current with the rapidly changing world outside our school’s walls?

Perhaps most importantly, I am forced to ask myself if I am preparing students for the ethical challenges they will face in this new world. In his 2013 New York Times article titled “The Perils of Perfection,” Evgeny Morozov details the pitfalls we face as a society when technology is used to solve problems for economic gain without regard to the humanistic threats the solutions would pose to society.3 It might seem like an incredible advancement to be able to implant a chip into an individual’s brain that gives them instant access to all the information available on Wikipedia. But, what do we do if such a chip gets hacked? It will be wonderful to cure diseases like cancer and heart disease, but how are we going to deal with issues of overpopulation and resource scarcity that will ensue? Globalization, driven by technology, is reshaping the human experience. Digital applications that eliminate memory loss, medical advancements that allow for the genetic altering of unborn children, and programs that allow social media accounts to posthumously communicate on our behalf using algorithms to determine what we probably would have posted – all could be possible in the near future. Each advancement comes with ethical strings that threaten our human identity.

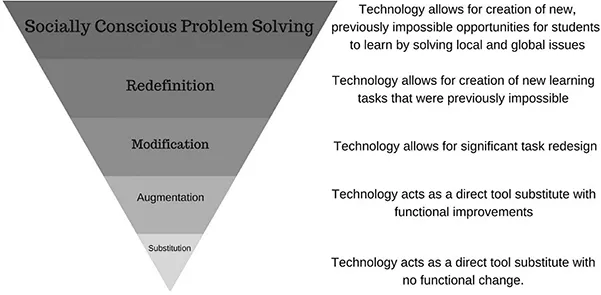

In 2006, in the midst of the Internet age, Ruben Puentedura developed the SAMR model to direct technology integration in schools. SAMR is an acronym for Substitution, Augmentation, Modification and Redefinition. The model guides educators from using technology to simply replace analog lessons toward innovative uses toward innovative uses of digital tools. For Puentedura, “redefinition” is the highest form of educational technology utilization in schools. He explains it as, “using technology to create completely new tasks, previously inconceivable.”4

Many schools and educational systems are still using SAMR to drive their technology integration. Many more have still yet to embrace technology as a necessary part of the learning experience. Yet, SAMR is already insufficient to describe the technology integration to which we should be aspiring in this complex time.

With the world we live in being constantly transformed by previously unimaginable advances and the ethical dilemmas that come with them, educational redefinition must evolve where technology is used beyond the creation of new learning experiences (Figure 1.1). If education is to keep pace with the Fourth Industrial Revolution outside of our schools, it must empower our next generation to be both solutionary and socially conscious. Learning must be seen as a vehicle for creating solutions to issues that threaten the health of our global society at the local, national and international levels. Much of the content we teach in schools has a practical application to help our fellow humans. Students should not have to wait until graduation to experience the relevance of their learning.

Figure 1.1 SAMR model adapted for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Fernando Reimers, Director of the Global Education Innovation Initiative and International Education Policy Program at Harvard University believes that the current landscape of our global society requires us to focus on pedagogies that empower students. “Education,” he claims, “should cultivate the agency, voice and efficacy of people. We need to help learners develop the ability to use what they know to solve problems.”5

When Stephen Ritz left a box of vegetable seeds behind the radiator in his classroom in the Bronx Borough of New York City, he had no idea that the trajectory of his teaching career and his school community was about to drastically change. As the seeds grew, so did his students’ curiosity. Children in his area, both the poorest and hungriest congressional district in the United States, rarely had opportunities to learn about healthy food and how it grows. The urban environment, in which almost 50 per cent of his students were homeless and living without a fixed address, was devoid of farms, gardens and places to buy fresh produce. Areas like this are known as “food deserts,” and nowhere in the United States are there as many hungry people as there are in the South Bronx.6

In order to both satisfy his student’s curiosity and to provide them with healthy food, Stephen began teaching through aeroponic gardening. Instead of learning about photosynthesis and other required curriculum from books, his students began learning in order to better grow crops in the school. Soon the culture of the struggling sch...