- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Preface to Shakespeare's Tragedies

About this book

This book is a study of four of Shakespeare's major tragedies - "Hamlet", "Othello", "King Lear" and "Macbeth". It looks at these plays in a variety of contexts - both in isolation and in relation to each other and to the cultural, ideological, social and political contexts which produced them.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Shakespeare’s England

1 Religious and philosophical developments

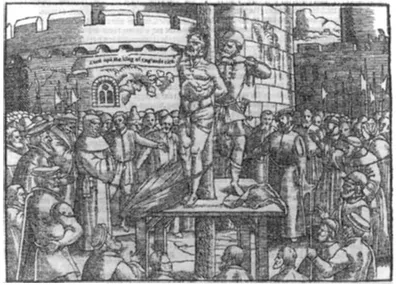

One of the best-selling, and certainly one of the most influential, books in the reign of Queen Elizabeth was a collection of gruesome descriptions of tortures, mutilations and executions. First published in 1563, it was originally entitled Acts and Monuments, and we now know it as Foxe's Book of Martyrs. A typical incident from the book is illustrated on p. 7: the execution of William Tyndale, burnt at the stake, is vividly portrayed both in the text and in the accompanying engravings. The author of Acts and Monuments, John Foxe, was an English Lutheran who fled abroad during the reign of the Catholic queen, Mary Tudor, and the martyrs whose lives he chronicles and whose deaths he describes so very vividly are not, for the most part, simply Christians who suffered under pagan oppression: they are Protestants, like Tyndale, who died at the hands of Catholic persecutors. It is a book which aimed to keep alive in Protestant hearts the memory of Catholic brutalities, to remind English church-goers of the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition (during a period when there was a continued and justifiable fear of a Spanish invasion), and to confront the young Church of England with a dehumanized image of the Catholic enemy. Queen Elizabeth ordered a copy of the book to be kept in every parish church alongside the Bible and The Book of Homilies, and if there was one single book of stories (apart from the Bible itself) which Elizabethan men and women might be expected to have known, that book would have been Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

The Book of Martyrs was one weapon in the major cultural battle of sixteenth-century England: the battle to redefine the central values of English society. These values had their roots in religious belief and religious practice, and the redefinition of them eventually involved no less than a complete restructuring of men's and women's beliefs about reality itself. Thus, the religious and philosophical developments of the period immediately preceding Shakespeare's own working life were intimately connected with the everyday fabric of social life in sixteenth-century England.

In short, the period from 1534 to 1603 saw the divorce of English religious thinking from that of Rome and the asserting and defending of a religious independence which was also a political independence. The history and cultural effects of the English Reformation are complex and multiple, and what follows is no more than a rough sketch. No historical process is neat, and no changes are ever clean-cut. Yet changes there are, and the important one for England in 1534 was that the Parliament of Henry VIII passed the Act of Supremacy, which asserted that the 'King's Majesty justly and rightfully is and oweth to be the supreme head of the Church of England'. At the beginning of the reign of Henry VIII, England was a member of a closely-knit community of nations who shared allegiance to the papal authority of Rome. Its religious institution enjoyed a great degree of autonomy from lay controls: it could make its own laws and it enjoyed great wealth, separate from the wealth of the English political institutions it was supposed to serve. Throughout the reigns of Henry's son Edward VI, and of his daughters Mary I and Elizabeth I, England was being pulled this way and that between old allegiances and new independence. By the end of the reign of Henry's daughter Elizabeth, the Church of England had taken root as a national institution. Elizabeth, as head of state, was also head of that Church. And if one result was that the Church of Elizabeth was free from subjection to any external authority, another result was that the Church itself had as much of a vested interest in the kingdom of England as it had an interest in the Kingdom of God.

Martyrdom of William Tyndale from Foxe's Acts and Monuments.

The establishing of the Elizabethan Church did not take place easily. In what is often referred to as the 'Elizabethan compromise', the institution needed to win grass-roots support from a population, many of whom were indifferent or hostile to the moderate Protestantism which it espoused. Changes occurred slowly. Many of the clergy who officiated at the Anglican mass in the reign of Elizabeth had been Catholic parish priests during the time of Mary Tudor (and some of them had been Protestant ministers before that during the reign of Edward VI). A sign of the Church's weakness at the beginning of Elizabeth's reign was the necessity for the Act of Uniformity of 1559, which made it illegal for men and women to fail to attend Church on Sundays and holy days, and which imposed large fines (never systematically levied) for absenteeism. The measure was never fully successful: one study of church attendance in Kent in the late sixteenth century has .estimated that absenteeism was regularly in the region of 20 per cent. Thus, if the growth and establishment of the Protestant Church is the dominant theme in the history of English Renaissance philosophical and religious developments, an essential sub-plot is that of the very real reactions against it. Those reactions sometimes took the form of adherence to older Catholic beliefs; sometimes they broke out into a Puritan denunciation of the incompleteness of Elizabeth's reforms; sometimes they manifested themselves as indifference towards the Elizabethan Church; and occasionally they were expressed in terms of outright atheism and a rejection of Christian belief in Divine Providence. The Elizabethan compromise offered new patterns of belief - but it also offered new possibilities of unbelief.

Resistance to the new Anglicanism tended to intensify the further one travelled from London. The North of England, in particular, remained a stronghold of the Catholic faith. The Northern rebellion of 1569-70 was motivated to a great extent by the Catholicism of its leaders; the Earl of Northumberland proclaimed at his trial that 'Our first aim in assembling was the reformation of religion and preservation of the Queen of Scots, as next heir'. As ever, the question of religion is closely related to the problem of the succession, and articles of religious faith are almost inseparable from issues of political loyalty. The reign of Elizabeth saw only four people executed for heresy, in contrast to the hundreds of Protestants burned during the reign of Mary Tudor. Elizabeth's administration did, however, execute two hundred Catholic priests and laypersons — but the crime they were charged with was treason.

If some of the initial opposition to the new religion was, like Northumberland's, based on positive convictions, a greater part of it probably had more to do with habit — the tendency on the part of many people to cling to the traditional forms of worship with which they had grown up. By the end of Elizabeth's reign, however, this kind of inertia was working in favour of the institutionalized Church of England rather than against it: people had got used to the ways of the Elizabethan Church and had claimed it as their own. If the ways of life, of thought and of belief which it advocated took time before they established themselves as part of the pattern of English life, they did eventually become a part of the national consciousness. Throughout Elizabeth's reign the Church of England fought a slow and unexciting battle for the allegiance of the English nation.

During the early stages of its history, up to the mid-1570s, that battle was waged largely against a traditionalist allegiance to Catholicism. During the 1580s and 1590s it became clear that the Church as a political and religious institution needed to fight on two fronts - both against the Catholic enemy and also against a growing discontent within the radical Protestant ranks at the increasing conservatism of the Elizabethan Church itself. The Puritan attack on the Elizabethan Church sometimes took the form of calls for moderate reform, while at other times it was separatist and revolutionary. Between 1580 and 1640, the relationship between the Anglican Church and the Puritan tendency veered from outright conflict to some degree of co-option. The more radical forms of Puritanism (and most particularly the forms which threatened the intimate alliance of Church and state) were gradually excluded from the Anglican fold, and the resulting growth of Puritan sects was to prove a problem for later ecclesiastical authorities. But the Church of England itself had been influenced from the very start by beliefs, practices and values associated with Puritanism. Even some of the more extreme theological positions, such as a belief in the Calvinist doctrine of election (see below), were shared by mainstream Anglican Protestants and radical Puritans. Indeed, what usually differentiates the Puritan from the Protestant in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries is not so much a matter of theological beliefs, as the impact of those beliefs on the everyday organization of social life, and most particularly on the organization of the Church.

The difference between Protestant and Catholic beliefs was more fundamental. To put it crudely, the most important difference between sixteenth-century Catholicism and sixteenth-century Protestantism was this. The Catholic believed that for men and women to understand God, they needed a rigid structure of spiritual authority, whereby God's mysteries could be explained to them. This structure was historically, as well as theologically, validated and depended upon the original nominating of St Peter as 'the rock' upon which Christ built his church. Thus Christ's authority as mediator passed to St Peter, the first pope; Peter's authority was handed down throughout generations of popes to the present day, and the present pope delegates that authority throughout the hierarchy of the Church, through cardinals, bishops, down to the parish priest. The structure of the priesthood was thus a vital channel which connected man to God, and the sacraments, principally The Mass, were the means by which God's grace was communicated.

For the Protestant this was not so. The typical official of the Protestant Church is not a priest with special authority partaking of God's holiness, but a minister, whose wisdom is to be respected, but who is a pastor rather than a mediator between God and man. Men and women approach God and partake of his holiness not by virtue of a mediating priest or hierarchy of authority, but through one's own personal and individual faith. Consequently, a way of thinking grew up in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which has been identified as 'Protestant' (although it was not exclusively the property of those men and women who worshipped in a Protestant Church). Rejecting the authority of ancient traditions, the cornerstones of Lutheran Protestantism were the doctrine of justification by faith alone, and the importance of the Bible as the word of God. There was also a great emphasis on the experience and the conscience of the individual. The answers which Protestantism offers to questions of faith and morality emphasize the primacy of the individual conscience, guided by a careful and honest reading of the Bible. The Bible, being the word of God, will provide advice and instruction. Good Christians, using their intelligence and goodwill, will know when they are in the right, since they will hear God's word telling them what to do.

Central to Calvinism (the brand of Protestantism founded by Jean Calvin) was the doctrine of predestination. This maintains that God has already decided who is to be saved and who is to be damned eternally, and that there is nothing anyone can do to change that. As Jean Calvin asserted in his Institutes of the Christian Religion:

God once established by his eternal and unchangeable plan those whom he long before determined once for all to receive into salvation, and those whom on the other hand he would devote to destruction. We assert that, with respect to the elect, this plan was founded upon his freely given mercy, without regard to human worth; but by his just and irreprehensible but incomprehensible judgement he has barred the door of life to those whom he has given over to damnation.

(Isobel Rivers, Classical and Christian Ideas, Allen and Unwin, 1979 p. 124)

The 'doctrine of election', as it is sometimes called, maintains that those who are saved will know that they are saved. They have the certitudo salutis – the certainty of salvation – and it is, indeed, a sign of salvation that one knows one is already saved! For the Calvinist in moments of confidence, this is a wonderfully reassuring doctrine, of course. But it can be a terrifying doctrine too, since any moments of doubt might then be read as a sign that one is not really one of the elect after all. At its most intense, this leads to a state of extreme psychological insecurity, whereby the individual is constantly seeking for signs of grace in his or her own life so as to be reassured that salvation is, after all, guaranteed.

If the doctrine of election sometimes leads to this sort of interpretative paranoia, it is only an extreme example of something which is common to Protestantism, even in its less neurotic manifestations. For the Protestant frame of mind is by nature one which stresses the need for the individual to be constantly engaged in an act of interpretation whether one is checking oneself for signs of election, or examining the nature of the Faith by which one was to be saved. The traditional sixteenth-century Catholic could safely leave matters of interpretation (whether of the Bible or of social behaviour or of natural phenomena) in the hands of a priest, whose function it was to provide a valid and authoritative explanation for such things. The Protestant, however, was encouraged, or even commanded, by the logic of Protestantism itself to ask about the meanings of things.

Many historians have related the spread of Protestantism to other features of English Renaissance history. Among the developments which have been analysed in the light of the growth of Protestant thought are the increase of literacy in the sixteenth century, the rise of scientific discovery and the rise of capitalism. The first of these, the relationship between Protestant forms of thought and attitudes towards language, will be dealt with in more detail (pp. 32-4). The second and third will bear a little explanation here.

Protestantism and scientific thought

The influence of Protestantism upon the development of scientific thought has been described in two main ways. Firstly, it has been looked at in institutional terms. The sixteenth-century Catholic Church has been seen as an extremely conservative institution, blocking scientific exploration on the grounds that it is not good for man to enquire too deeply into the heart of nature, and perhaps out of a fear that some of its own sacred beliefs might be compromised by the discoveries of scientists.

The second element in the relationship between Protestantism and the rise of science involves the Protestant's enquiring and sceptical cast of mind, in conjunction with the stress laid by Protestant thought on empirical observation and interpretation. These trends, it is argued, laid the foundations for the development of a scientific method. 'Inductive' reasoning, whereby general principles are gradually built up from the available empirical data, has been a central principle of scientific enquiry for so long that it now seems a natural way of progressing. In fact it only dates, as a recognized methodology, from the late sixteenth century. One of the first major theorists of this way of reasoning was Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor of England in the early seventeenth century and influential philosopher of the new scientific expansion. Bacon wrote and published books about learning and science, partly in an unsuccessful attempt to explain to James I the principles of the new scientific movement, and thereby to persuade him to allocate more money to scientific research. His first attempt, The Advancement of Learning, was written in English in 1605; the second, the Novum Organum in Latin in 1620. The following quotation comes from the latter.

There are and can be only two ways of searching into and discovering truth. The one flies from the senses and particulars to the most general axioms, and from these principles, the truth of which it takes as settled and immovable, proceeds to judgement and to the discovery of middle axioms. And this way is now in fashion. The other derives axioms from the senses and particulars, rising by a gradual and unbroken ascent, so that it arrives at the most general axioms last of all. This is the true way, but as yet untried.

(Translated from the Latin by Ellis and Spedding in Works of F. Bacon, Vol. IV, 1843, p. 50)

Bacon's two ways of'searching into and discovering truth', it will be noted, both start out from 'the senses and particulars' and proceed towards general rules in their various ways. Searching into and discovering truth by appeal to traditional authority is not even considered by Bacon,

The story which may be seen as dramatizing the new attitudes towards scientific enquiry is the famous one of Galileo, who, at the end of the sixteenth century, came up with proof that the earth did indeed go round the sun (rather than vice versa) and who was forced by the Church to recant and deny his own findings. Galileo himself was no Protestant, but in the popular version of this story he appears as a kind of Protestant tragic hero, relying on empirical evidence rather than on the authority, bullied by a repressive Church into finally denying his own...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- FOREWORD

- Dedication

- INTRODUCTION: 'Soule of the Age!': The historical context of Shakespeare's plays

- PART ONE: SHAKESPEARE'S ENGLAND

- PART TWO: SHAKESPEARE AND THE THEATRE OF HIS TIME

- PART THREE: CRITICAL ANALYSIS: HAMLET (1601) OTHELLO (1604) KING LEAR (c. 1605) MACBETH (1606)

- PART FOUR: REFERENCE SECTION

- Further reading

- Appendix: The theatres of Shakespeare's London

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Preface to Shakespeare's Tragedies by Michael Mangan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Shakespeare Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.