This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

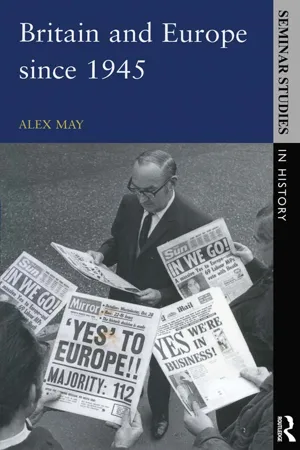

Britain and Europe since 1945

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is a succinct, timely introduction to one of the most highly charged political questions which has dominated British politics since 1945: Britain's position in Europe. The study traces the evolution of British policy towards Europe since 1945, presenting the full international context as well as the impact on domestic party politics - including an analysis of the divisions in the Conservative Party under John Major.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Britain and Europe since 1945 by Alex May in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du monde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE: THE BACKGROUND

1 BRITAIN AND EUROPE BEFORE 1945

‘I am here in a country which hardly resembles the rest of Europe’, the French philosopher Montesquieu declared during a visit to Britain in 1729. A number of historians have confirmed the substance of his observation. Indeed, Alan Macfarlane has argued that as early as the fifteenth century the decline of serfdom, the rise of a market economy and the existence of a distinctive legal system had produced in England (although not necessarily in Wales, Scotland or Ireland) ‘a society in which almost every aspect of the culture was diametrically opposed to that of the surrounding nations’ [56 p. 165]. While such arguments should not be pressed too far, most historians would agree that the developments of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries reinforced rather than diminished whatever elements of separateness and distinctness existed. The religious Reformation, although paralleled by developments on the continent, was unique both in its origins and its consequences, and provided the English and lowland Scots with a peculiar sense of providential destiny. The political changes of the mid-seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries – the Civil War of 1642–60, the ‘Glorious’ Revolution of 1688 and the Act of Union of 1707 – reinforced this sense of uniqueness. The integration of Britain itself was accompanied by a new and assertive role as a maritime power and by the steady accumulation of a vast overseas empire. War, religion, empire, prosperity and parliamentary ‘freedom’ combined to forge a widespread and active ‘British’ patriotism, which defined itself largely by opposition to the culture of continental Europe. The industrial revolution, which transformed the British economy earlier and more thoroughly than any of its continental neighbours, gave added impetus to the ‘public myth of uniqueness’ which had already taken hold [47 p. 149, 52].

The nineteenth century was Britain's heyday, the period of its greatest relative economic and political power. The British Empire encompassed a quarter of the earth's land surface and a similar proportion of its inhabitants. It was perhaps inevitable that the British should see themselves not only as unique amongst Europeans, but also as separate and different; and that British policy towards the continent should be characterised (in Lord Salisbury's famous words) by ‘splendid isolation’. Yet even at this high point many recognised that Britain was still a part of Europe; that British culture and British power were reflections of more general European trends. Towards the end of the century, the differences between Britain and its continental neighbours palpably diminished. Other countries industrialised – some more proficiently than Britain. The Scandinavian countries, Belgium, the Netherlands and France (after 1870) maintained political systems at least as ‘liberal’ and democratic as Britain's. Moreover, centuries of history confirmed that Britain could hardly remain indifferent to developments across the Channel. By the close of the century the dangers of isolation were becoming apparent. Europe was increasingly dominated by a powerful and expansionist Germany, which now embarked on an ambitious naval programme. Colonial conflict was becoming ever more likely. The South African war of 1899–1902 administered a sharp shock to the British psyche: the whole of Europe was hostile, while all available British forces were tied up by a handful of Dutch settlers. As the new century dawned, British politicians scrambled to shore up the ‘balance of power’, and with it Britain's position. Alliances were concluded with Japan in 1902, with France in 1904, and with Russia in 1907. By these alliances, however, Britain merely increased the tensions in Europe, which was now firmly divided into two armed camps. When war finally came in 1914, it was almost a relief [15, 55].

BRITAIN AND EUROPE BETWEEN THE WARS

The First World War was unlike any previous war and very different from the war which had been expected. It lasted more than four years, cost upwards of 20 million lives, and resulted in the devastation of large parts of Europe. Three empires were dismembered (the German, the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman), and a fourth (the Russian) collapsed. Britain and France emerged victorious only through the mobilisation of their extensive imperial resources and the intervention of the United States. President Wilson demanded a generous peace. Britain, and even more, France, demanded retribution. The resultant Treaty of Versailles was a dangerous mismatch of idealism and vindictiveness. Germany lost large chunks of primarily German-speaking territory, was forced to pledge vast sums in reparations (most of which were never paid) and suffered the indignity of numerous restrictions on its national sovereignty – hardly the most favourable conditions in which to embark upon the experiment of democracy. Meanwhile, peace was entrusted to the twin principles of national self-determination (which resulted in the ‘Balkanisation’ of central and eastern Europe) and collective security, the latter to operate through a League of Nations dependent on consensus and the voluntary co-ordination of national policies. At one stage, Britain promised to guarantee France's security – but only on condition that the United States did so too. America's withdrawal from the agreement, from the League of Nations, and indeed from any entanglement in the affairs of continental Europe, nullified the proposal. Without such support, Britain was still far from ready to make an irreversible ‘continental commitment’ [55].

One of the major effects of the war was to increase Britain's preoccupation with the empire and Commonwealth. On the one hand, the empire experienced one last burst of expansion, with the acquisition of ‘mandated’ territories in the Pacific, Africa and the Middle East. On the other, a series of crises in India, Egypt and Ireland diverted resources and absorbed government and public attention. Some historians have argued that the interwar years illustrated the steady decline of British imperial power. Others have argued that, strategically and politically, the empire was more important to Britain than ever [53, 54]. In economic terms, this was certainly true. Between 1910 and 1914, the empire accounted for 25 per cent of Britain's imports and 36 per cent of its exports; by 1930–34 the figures had increased to 31 and 42 per cent and by 1935–39 to 39.5 and 49 per cent. British overseas investment also increasingly followed the flag, 46 per cent going to the empire in 1911–13 and 59 per cent in 1927–29 [13 p. 261].

Moreover, the war accelerated the evolution of the self-governing ‘Dominions’ (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) into semi-independent states, as recognised by their separate representation in the League of Nations and by the Statute of Westminster in 1931. The altered status of the Dominions made it more important for Britain to frame its foreign policy with one eye on its imperial partners, if the unity of the empire were to be maintained. This effectively limited Britain's ability to play a major role in Europe. A succession of incidents in the early 1920s revealed the potential for friction and disunity. In 1922 Canada and South Africa refused to support British intervention at Chanak, designed to prevent Turkey from re-establishing a foothold in Europe. In 1924 Canada again led the way, by refusing to ratify the Treaty of Lausanne, on the grounds that it had not been represented at the negotiations. In 1925 it was the British government which broke ranks, agreeing by the Treaty of Locarno to guarantee the borders between France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, without any similar commitment on the part of the Dominions. Locarno caused a major rift in Anglo-Dominion relations, which subsequent British governments were anxious to heal. Significantly, the Foreign Secretary at the time, Austen Chamberlain, defended the Treaty on the grounds that it reduced rather than extended Britain's liabilities in Europe [15 p. 106, 55].

Britain stood aloof from all the major developments in the pre-history of European integration in these years. A British branch of the Pan-Europa movement was established, but it was dominated by imperialists such as Leo Amery, who saw European unity (without Britain) as the natural counterpart to closer union of the empire. British industry remained outside the negotiations which led to the formation of transnational cartels in steel and other industries in the late 1920s. When the French Foreign Minister, Aristide Briand, proposed European economic integration leading to ‘some kind of federal bond’ [49 p. 220], in 1929, it was partly the British reaction (although, much more, the world economic depression following the Wall Street crash and the breakdown of democracy in Germany) which ensured that the proposal led nowhere [59], The main effect of the Briand plan in Britain was to strengthen the hand of those who favoured economic integration of the empire. ‘If we do not think imperially, we shall have to think continentally’, was Neville Chamberlain's, as he saw it sombre, warning in 1929 [50 p. 79, 49]. The economic depression of the 1930s led to the abandonment of free trade with Europe in favour of an imperial economic bloc. Robert Boyce has seen this period as the first of a series of ‘missed opportunities’ for Britain in Europe. Had British ministers proposed an ‘open-ended, non-federal, liberal approach to the re-establishment of a European-wide market’ instead of turning to the empire, they would have met with a widespread favourable response from other European countries [51 p. 31]. Be that as it may, British priorities were clear.

It was in these circumstances that the British policy of limited commitment to Europe took the form of ‘appeasement’, i.e. the policy of attempting to placate Germany by acquiescing in its overturning of the Versailles settlement. The origins of this policy can be traced back even to before the signing of the Versailles Treaty, when Lloyd George, largely unsuccessfully, tried to soften the terms to be imposed on Germany. It acquired greater force as a result of the Ruhr crisis of 1922–23, when French and Belgian troops occupied Germany, precipitating the near-collapse of the German economy and the first major crisis of German democracy. Successive British governments launched initiatives designed to produce a peaceful revision of the Versailles terms. It was not, therefore, a new policy which the Macdonald, Baldwin and Chamberlain governments adopted after Hitler came to power in 1933. What condemned their policy was the naivety and vigour with which they pursued it. Yet the pressures leading to such a policy were intense. The Dominions, by and large, opposed any commitment to Europe. The United States had retreated into its isolationist shell, cursing the ‘old’ world indiscriminately. Britain itself was overstretched. The British public was still wedded to support of the League of Nations. Finally, until his invasion of the rump Czech state in March 1939, Hitler was careful to portray his actions as merely pursuing the principle of national self-determination. Britain's abandonment of ‘appeasement’ came too late to retrieve the situation. Between March and August 1939 Britain and France made last-minute commitments to the remaining central and eastern European states. These did not prevent Hitler from invading Poland on 1 September 1939. Two days later, Britain was at war [12, 55].

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

The last year of peace and the first year of war witnessed a remarkable growth of pro-European federalist ideas and activities in Britain, sponsored in particular by the Federal Union movement [48, 57]. The latter, launched in July 1939, reached a peak of 12,000 active members organised into 300 branches, by May 1940. At one point the leader of the Labour Party, Clement Attlee, gave his support, declaring that ‘Europe must federate or perish’ [48 p. 118]. The Foreign Office was initially sceptical. Nevertheless, the government appreciated the propaganda value of European federalist ideas. Various proposals were discussed but these were soon narrowed down to the central concept of Anglo-French union. Even as Hitler was unleashing his devastating blitzkrieg against France, Jean Monnet and Sir Arthur Salter were entrusted with drafting a declaration of ‘indissoluble’ economic and political union. The British Cabinet approved the text on the afternoon of 16 June 1940 and immediately transmitted it to the French government at Bordeaux [Doc. 1]. The French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud, was ‘transfigured with joy’; but the majority of his colleagues argued that the proposal could do little to help a France now defeated and overrun by German forces. Reynaud resigned, and his successor General Petain initiated the negotiations which left half of France under German occupation and the other half under the control of the Vichy regime. General de Gaulle – at that stage a mere Under-Secretary in the War Department – declared his intention to continue the war as leader of the ‘Free French’, but it was clear that without British support he amounted to little [30].

The events of May and June 1940 marked both the high point of support for European federation in Britain and the beginning of its effective demise. The Federal Union's membership dropped below 2,000 by the end of 1940. Its ideas subsequently enjoyed a new lease of life on the continent, providing inspiration to the anti-fascist resistance, which (especially in France and Italy) became firmly committed to a federal reconstruction of Europe. Many of the governments-in-exile which gathered in London during the war also became fervent advocates of a federal solution. In Britain itself, however, the idea of European federation receded into the distant background [48, 57].

Britain's wartime experience was very different from that of the other European countries which would later form the European Union.* After the fall of France, Britain and its empire ‘stood alone’. Britain's retreat from Europe, at Dunkirk, was turned into a national victory. Its national institutions stood the test and its sense of national identity and pride emerged strengthened by the war. There was no crisis of the nation-state, as there was in Germany and Italy, and in the countries which they conquered. Moreover, the globalisation of the war served to emphasise the importance of Britain's extra-European links. Europe was but one of two major, and innumerable minor, theatres of war. The empire and Commonwealth were crucial to Britain's survival. But it was only with the help of the Soviet Union and the United States that Britain was able to turn survival into victory. The fact that Britain was the weakest of the ‘Big Three’ merely underlined the importance of maintaining good relations with the emerging ‘superpowers’.

British postwar planning did not really get under way until 1944–45 and then it was largely predicated on the hope of continued co-operation with both Russia and the United States. It was accepted that a strong France was now a major British interest, and the British government fought successfully for French representation in the United Nations Security Council, and for a French occupation zone in Germany. Nevertheless, the building of a closer relationship was complicated by Britain's own financial and economic weakness, by differences over Germany (which France wanted dismembered) and the Middle East (where France was attempting to re-establish its empire), and by the general difficulty of doing business with de Gaulle. The latter's demands for recognition of French ‘grandeur’, personified by himself, caused Churchill on several occasions to regret the way he had built de Gaulle up. De Gaulle in turn never forgave Churchill (or indeed Britain) for his candid assertion that in the event of any quarrel between France and the United States, Britain ‘would almost certainly side with’ the United States [30 p. 56].

As the war in Europe drew to a close, the idea of British leadership of a more integrated western Europe again gathered support in Foreign Office circles. In an influential memorandum on ‘Stocktaking after VE-Day’, Sir Orme Sargent argued that only by leadership of western Europe as well as the Commonwealth could Britain continue to rank as one of the ‘Big Three’ [46, 58, 60]. Nevertheless, Britain's main preoccupations lay elsewhere: with co-operation (rather than competition) with the United States and Russia; with consolidating the wartime unity of the empire and Commonwealth; and with the rebuilding of Britain itself. From being the world's greatest creditor nation in 1939, Britain had become the world's greatest debtor. Moreover, as a result of the war Britain had lost most of its overseas markets and was expected to run a balance of trade deficit of some £2 billion a year when American Lend-Lease (effectively a form of aid) came to an end, as it did abruptly, in August 1945. Britain would have to increase its production and exports dramatically if it were merely to maintain prewar standards of living. This was without any of the schemes for a welfare state which, by 1945, figured largely in the postwar planning of all the major political parties.

PART TWO: BRITAIN AND EUROPE SINCE 1945

2 LABOUR'S EUROPE, 1945–51

Domestic considerations were uppermost in British electors' minds when they voted on 5 July 1945 to elect a Labour government with a Commons majority of 146. The new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, was a good party manager but hardly a forceful or charismatic personality. The same could not be said of Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary until ill-health forced his retirement on 9 March 1951 (when Herbert Morrison replaced him). Unusually for a twentieth-century British government, the conduct of British foreign policy was firmly in the hands of the foreign secretary rather than the prime minister of the day. A former leader of Britain's largest trade union, the TGWU, and the dominant figure on the Labour right, Bevin was memorably described by Churchill as a ‘working-class John Bull’ [64, 78].

The hallmark of Bevin's foreign policy was Atlanticism – the pursuit of close co-operation with the United States. For that reason, he was often criticised by the left wing of his party, who favoured a more robustly ‘socialist’ foreign policy. A frequent charge was that Bevin had been ‘nobbled’ by the Foreign Office [76]. Later commentators gave the charge a different twist. In their view, Bevin and his successor Morrison were deluded by the Foreign Office, by Atlanticism and by a kind of folie de grandeur into being ‘anti-European’. Thus the scene was set for a series of ‘missed opportunities’ for Britain to take the lead in European integration [28, 43, 81].

Recent historians, with the benefit of access to private and Cabinet papers and Foreign Office files, have modified this picture to a large extent. Bevin did share a number of ideas and assumptions with his Foreign Office advisers, but these were by no means as ‘anti-European’ as has often been assumed [62, 78]. As early as 1927, he had advocated the creation of a European common market [50]. Almost his first act on entering the Foreign Office in 1945 was to call a meeting of his senior officials at which he outlined a ‘grand design’ for western European co-operation, based on a close relationship between Britain and France [Doc. 2a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- An Introduction to the Series

- Note on Referencing System

- Acknowledgements

- Part One: The Background

- 1 Britain and Europe Before 1945

- Part Two: Britain And Europe Since 1945

- 2 Labour's Europe, 1945–51

- 3 The Conservatives' Europe, 1951–57

- 4 Macmillan and the First Application, 1957–64

- 5 Wilson and the Second Application, 1964–70

- 6 Heath and British Entry, 1970–74

- 7 The Labour Governments, 1974–79

- 8 The Thatcher Governments, 1979–90

- 9 The Major Governments, 1990–97

- 10 The Blair Government, 1997-

- Part Three: Assessment

- 11 The Long Road to Europe

- Part Four: Documents

- Chronology

- Glossary

- Map: The European Union

- Bibliography

- Index