![]()

Section III

Strategy and organization

![]()

6

Sustainability for strategic advantage

The shift to flourishing

Chris Laszlo

Case Western Reserve University, USA

This chapter covers the fundamentals of sustainability for strategic advantage—why sustainability is a growing concern and strategic priority for companies in every sector, what leading companies are doing about it, and how they are doing it. It delineates two successive paradigms: embedded sustainability built on the business case for sustainability and the emergence of flourishing—the aspiration that human and other life will thrive on Earth forever—as the new and more inspiring purpose of business. The shift to flourishing does not abandon the earlier paradigm of embedded sustainability. It adds to it a shift in consciousness that changes who we are being, not only what we are doing. The idea proposed here is that embedded sustainability strategies can benefit from the addition of one other ingredient: reflective (or mindful) practices that increase our sense of connectedness to self, others, and the world. The addition of such practices doesn’t require more work; it simply changes the way we do our work and, more importantly, the results we achieve.

Assessing corporate sustainability today

Management thinker Peter Drucker once said, “Every single global and local issue of our time is a business opportunity in disguise.” Twenty years ago his observation would have been strongly counter to prevailing wisdom. In the 1990s environmental and social problems were considered to be a cost to most enterprises. It was the era of environmental, health and safety (EH&S) specialists, corporate social responsibility reports and ethical codes of conduct issued by senior leaders. In every sector CEOs were confronted with rising environmental and social regulations, growing consumer engagement and nonprofit activism. Yet it was mostly with a wary eye that business leaders responded to such pressures.

Today, Drucker’s wisdom has become widely accepted. A MIT Sloan Management Review–Boston Consulting Group survey showed that, by 2011, 67% of CEOs considered sustainability to be critical to competitive advantage (Haanaes et al., 2012). In 2013, a United Nations Global Compact (UNGC)-Accenture survey of 1,000 CEOs reported that 80% considered sustainability to be essential to competitive advantage (UN Global Compact, 2013). By 2014, mainstream corporations in every sector were proudly proclaiming that sustainability was at the heart of how they do business.

The rapid shift in business mind-set, from one of cost to one of profit opportunity, is impressive but also misleading. The same UNGC-Accenture survey found that nearly two-thirds of the CEOs felt that sustainability business value quantification was poor. Some 37% saw it as one of the major obstacles to further sustainability investments and projects. The report states, “Business leaders see a plateau effect in sustainability and are struggling to make the business case for action.” The survey also found that a gap persists between the approach to sustainability of the majority of companies—an approach centered on compliance, cost reduction, risk mitigation, and philanthropy—and the approach being adopted by leading companies focused on innovation and topline growth.

The shift in CEO mind-set toward sustainability as profit opportunity is also misleading because of resistance from middle managers. In my own survey1 of 502 mid-level managers across nine different companies in five sectors (fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs), chemicals, telecommunications, aerospace, and electric utilities), my firm asked the following question, “How would you say most managers in your company think about Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)?” A significant number of respondents gave weight to “public relations/window dressing” (22%) and to “ethics/save the whales” (17%). Organizations with visionary CEOs were finding it hard to progress where mid-level managers were not on board with sustainability.

A number of other studies have shown that sustainability performance tends to be focused on the low-hanging fruit of energy conservation and waste reduction. A 2011 McKinsey study on “The Business of Sustainability” found that the top reason given for addressing sustainability was “improving operational efficiency and lowering costs” (Bonini and Görner, 2011). While over 60% of companies of the nearly 3,000 companies surveyed said they were reducing energy and waste in operations, less than 20% said they were achieving higher prices or market share because of sustainable products. Reducing energy and waste along with reputation management remain the main vectors of corporate sustainability initiatives, leaving many additional sources of value creation untapped.

For all the above reasons, in 2015 sustainability remains poorly managed as a driver of business value. There is a profound need to deepen the practical understanding of sustainability for strategic advantage—why sustainability is a growing concern and strategic priority for companies in every sector, what leading companies are doing about it, and how they are doing it. There is also a widespread desire to understand “what’s next?” Business leaders and academics as well as the wider public want to know how sustainability practices are likely to change in the years ahead and what new benchmarks to expect for sustainability leadership.

To meet these needs, the chapter is divided into the following sections.

- The megatrends driving the market shift in how companies create sustainable value

- How leading companies leverage sustainability performance for value and profit

- Why today’s corporate sustainability is insufficient for both business and society

- Competing on sustainability performance: five “Winning Tomorrow” criteria

- Moving beyond the business case: reframing sustainability as flourishing2

The megatrends driving the market shift in how companies create sustainable value

Declining natural resources, radical transparency, and rising expectations are reshaping the way companies compete. These trends were first highlighted in Embedded Sustainability (2011) as part of the broader context for understanding the changing basis of how firms achieve competitive advantage (Laszlo and Zhex-embayeva, 2011). To the extent that environmental and social factors are still seen as relating to regulations or ethics rather than competition, they continue to be overlooked or underestimated. For example, while Americans are attuned to digitization and the emerging middle class in China and India, a majority continue to ignore or dismiss concerns about climate change (Hirt and Willmott, 2014). According to a 2014 Gallup poll, the percentage of Americans who “worry a great deal” about the quality of the environment actually fell from 43% in 2007 to 31% in 2014, with more than half of the decline occurring between 2012 and 2014 (Riffkin, 2014).

In Resource Revolution, two McKinsey authors call attention to the continued trend in natural resource consumption and the impending shortage of many key raw materials. In addition to growing scarcities in topsoil, fresh water, and cheap oil, the authors show that nonrenewable resources such as lead, tin, and chromium all have less than 20 years of reserves left based on current production rates (Heck et al., 2014). The impact of such shortages on agriculture, energy, electronics, aerospace, and construction is already being felt. The authors show how the worldwide growth of middle-class consumers, numerically driven by emerging markets, are accelerating these shortages and putting upward pressure on commodity prices. The downward trend in commodity prices during the 19th and 20th centuries, driven by productivity increases and the discovery of new untapped reserves, has been completely wiped out by the upward trend of prices in the past 16 years:

Prices for oil and energy have more than quintupled since 1998. Metals prices have tripled. Food prices have risen 75 percent. Just since the beginning of the twenty-first century, an index of commodity prices has risen almost 150 percent … Battles over oil, water, and food are the inevitable consequences.

(Heck et al., 2014, p. 36)

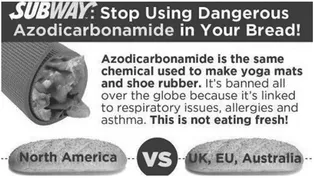

The second megatrend is radical transparency, defined here as the ability of any individual or organization to “see into” the life-cycle activities of a business, giving them insight into the company’s environmental, health, and social impacts at each stage from raw materials extraction to product or service end-of-life. Such transparency is driven by information and communications technology (ICT) as well as by the increased desire of consumers and activists to know how a product or service is sourced, produced, delivered, used, and disposed. Businesses can no longer hide negative impacts such as harm to human health, even when the impact is legal and the result of accepted practice. In 2014, the fast-food restaurant franchise SUBWAY® suffered from revelations that it—along with many bakery and confectionery businesses—was using a food additive called azodicarbonamide or ADA, a chemical compound also commonly used in yoga mats. In food items it is used to provide malleability,3 and specifically in breads ADA was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help extend shelf-life and maintain sponginess. Yet the disclosure that ADA was a possible carcinogen was widely publicized and eventually forced the company to eliminate its use. Figure 6.1 illustrates the efforts made by activists to stop the use of ADA in SUBWAY® products.

Figure 6.1 Activist campaign to stop the use of ADA in SUBWAY® products © foodbabe.com

The campaign to eliminate ADA from SUBWAY® breads points to the third megatrend: rising expectations. ADA had been widely in use by the food industry since the FDA approved its use as a food additive in 1962 (Andrews and Shannon, 2014). Its use was tightly regulated by the FDA in amounts considered safe for human consumption. Why should it suddenly lead to a public uproar forcing companies to find other ingredients in formulating their bread products? A similar question can be asked about bisphenol A (BPA), a plasticizer used in a wide array of consumer products from toys to baby bottles and in the inner lining of soda cans. BPA was discovered 100 years ago and commercialized 50 years ago. Its impact as a potential endocrine disruptor became publicized by 2007 (Okada et al., 2008). In 2008–2009 it became the subject of widespread concern and scrutiny, leading to its voluntary elimination in sensitive applications and to its outright ban in baby bottles in Canada and in the European Union following the European Directive (2011/8/EU) (Pollution News, 2009; Alberta Health Services, 2011; Vincent and Apostola, 2011). Of course, rising expectations concern not only human health impacts; they affect a wide range of sustainability-related issues in every sector of the economy.

Taken together, declining resources, radical transparency, and rising expectations are rewriting many manufacturing processes, service activities, and product designs. They are forcing companies to internalize impacts that were previously considered negative externalities. The three megatrends are, in summary, redefining the meaning of value creation for every business seeking to profitably serve its customers.

How leading companies leverage sustainability performance for value and profit

The McKinsey survey cited earlier found that a majority of companies were reducing energy and waste in operations, but that less than 20% were achieving higher prices or market share because of sustainable performance. Reputation management was revealed to be the next biggest reason given for why companies engaged in sustainability efforts. These findings are symptomatic of the mind-set found in many organizations today: sustainability performance is seen primarily as a way to avoid risks related to corporate or brand image and to achieve eco-efficiencies from reducing energy or waste. Topline and intangible sources of value creation related to increased sales and higher margins from product or service differentiation, entry into new markets, and business model innovation represent bigger profit opportunities yet are less commonly pursued.

To tap into the full range of value creation opportunities, managers need to use a different approach. Whether aiming for risk and cost reduction or topline growth, they need to ask the right questions about the business logic for sustainability performance. Mitigating risk is about avoiding value destruction by managing potentially costly liabilities, as BP discovered in the Deepwater Horizon debacle of 2010. At the efficiency level, the question is one of operational excellence: how can embedded sustainability contribute to greater savings along the product life-cycle? At the product differentiation level, the inquiry is about consumer expectations and how these are changing to incorporate ever greater environmental, health and social attributes. In terms of new market opportunities, the focus is on business models: how can businesses find profitable solutions to global problems? One such new market or business model example is that of meeting the unmet needs of poor consumers in emerging markets, as is the case for wireless telecommunications in India and Africa (for example, Bharti Airtel) and distributed renewable energy in rural India (for example, Selco). At the level of image and reputation, the issue goes beyond risk management. It goes to the core identity of the company: the question becomes to what extent social and ecological goals are essential parts of its mission or culture. At the level of business context, it is about shaping government regulations or industry standards that favor the market leaders over the competition.

In many instances, it is not sustainability in itself that increases profitability. Instead, environmental and social strategies force companies to acquire constituent capabilities which in turn allow them to develop new competences that lead to competitive as well as sustainability advantages. What we mean by constituent capabilities are the “building-block” skills—both individual and organizational— such as full-cost analysis or stakeholder collaboration. These capabilities tie together, over time, to create new competences such as process innovation, cross-functional management, and the ability to develop a widely shared strategy vision (Laszlo and Zhexembayeva, 2011, p. 69). In other words, getting good at man...