This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

J E Thomas examines the historical roots of Japanese social structures and preoccupations and he sets these within the broad chronological framework of Japan's political and military development. The book can thus serve as an introduction to modern Japan in a more general sense - but its focus throughout is on the people themselves. Professor Thomas gives due attention to the Japanese mainstream; but he also discusses those other sections of the community which have traditionally been underprivileged or marginalised - most obviously women, but also minority groups and outcasts - and the Japanese attitude to foreigners beyond her shores.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Modern Japan by J.E. Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia japonesa. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Out of Isolation

Overleaf ▶

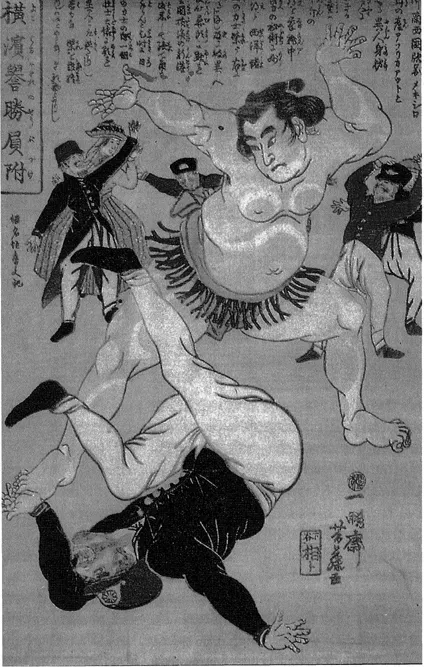

Japanese beating a foreign seaman

(Nishaka-e print by Ipposai Hoto)

Japanese beating a foreign seaman

(Nishaka-e print by Ipposai Hoto)

Out of Isolation

On 3 January 1868, the emperor of Japan was ‘restored’ to what was claimed as his rightful position in society. This is accepted as the point and the event from which the modern history of Japan begins. Although the circumstances were turbulent and violent, this was by no means a sudden change, even though for the Japanese today it is perhaps the most important event in their history. They regard the years after the Restoration with awe, and attribute the phenomenal ‘catching up with the west’ exemplified by economic and military success, as due to the wisdom and power of the restored emperor. Quite how much real power or even influence modern Japanese emperors have had, it is impossible to know: But the question is important, and we shall return to it. What is certain though is that like most major upheavals in societies, the Restoration was the culmination of a complexity of events. To understand this complexity, it is necessary to be aware of the nature of Japanese society and its nineteenth-century inheritance.

From 1185, if there was an individual who was most powerful in Japan, it was the shogun, whose full title means ‘barbarian-subduing generalissimo’. In that year the famous Kamakura shogunate was established, and the emperors’ power, over succeeding centuries, was reduced, and sometimes eliminated. Although there is some truth in the commonly held belief that the shogun had absolute power, we shall go on to see that his authority was moderated both by the presence of powerful clans who often usurped power for themselves, and by the refusal of some emperors to be compliant. The battles for power by the aristocracy led to very destructive civil wars, which came to a peak and to an end in the closing years of the sixteenth century. It was then, in 1598, that Hideyoshi, to whom we shall return because of his Korean adventures, died.

His followers were beaten in a famous battle at Sekigahara in 1600 by Tokugawa leyasu, who, despite the fact that he was a guardian of Hideyoshi’s heirs, prompted the suicide of most of them, and the execution of the last, an eight-year-old boy. Because of his lineage – he claimed he was of the house of Minamoto, the founders of the Kamakura shogunate – he was appointed shogun in 1603. Then began a remarkable period in Japanese history, noted for its peace, stability and isolation from the rest of the world. This period, in which the Tokugawa shoguns reigned supreme, is called the Edo (or sometimes, in more antiquated language Yedo) Era, Edo being the name of the capital city of Tokyo before the restoration of 1868. Immediately after Edo was established as the shogunal capital, it seems to have become a grand city where ‘money flowed like water’.1 A European visitor to the castle in 1609 observed that at the first gate there were 2,000 armed guards, at the second another 400, and at the third 300. The armouries, he reported, contained enough equipment to arm 100,000 men.2 The administration of the regime was known as the bakufu, meaning ‘field government’. Within the bakufu, power was exercised by a handful of men appointed by the shogun. But below them was created an elaborate and powerful bureaucracy, a phenomenon which made their administration as slow as it is under their bureaucratic heirs in modern Japan.

Ieyasu is one of the most important figures in Japanese history. His achievements, notably bringing peace to a country desperate for it, derived from remarkable personal characteristics, many years of experience and, especially a capacity for introspection which both controlled and directed his behaviour. In his advice to his heirs he wrote:

The strong manly ones in life are those who understand the meaning of the word Patience. Patience means restraining one’s inclinations. There are seven emotions, joy, anger, anxiety, love, grief, fear and hate, and if a man does not give way to these he can be called patient. I am not as strong as I might be, but I have long known and practised patience. And if my descendants wish to be as I am … they must study patience.3

In the next forty years the Tokugawa shoguns established a regime which was to last for some two hundred and fifty years. Their overriding concern was to ensure the stability of Japan, and concomitantly their power in it.

A key factor was the relationship between the shogun and the imperial court which remained in Kyoto, and would continue to do so until 1868. The attitude of the Tokugawa shoguns to the emperor was respectful, since there could be no possibility of a shognn usurping the throne, because of the acceptance of the tradition of the singularity and purity of the imperial lineage. But the shogun was aware of the fact that the emperor could validate the authority of a new shogunate, and thus unseat the Tokugawa clan, a process which had happened before, would happen at the time of the Restoration, and in power politics generally, afterwards. So the court was tightly controlled by such devices as requiring imperial appointments to have the approval of the shogun, and the placing of family members in key posts. As well as such coercion the shoguns increased the wealth of the emperor and his court, a wise tactic for obvious reasons, especially since in the previous history of the dynasty, some emperors were impecunious to the point of beggarhood.

It was natural that the shoguns should take steps to increase their own wealth, and they did so by the reallocation of resources, notably of course land. Such tactical redistribution was used as a means of penalising those great lords called daimyo, literally ‘great name’, who had fought against the Tokugawa house, and rewarding their allies, which reinforced the latter’s loyalty. However, the shoguns were well aware that the power of the daimyo was still a reality, and that the loyalty of their retainers could soon be deflected for an assault upon their newly established authority. The daimyo were therefore restricted by a network of constraints on their ambition. They had to seek the agreement of the shogun to a marriage, for example, and they had to take an oath of support upon accession. Again, as required, they had to bear the costs which were often crippling, of public works. But the most important, and probably most effective weapon of control was a requirement of domicile. This meant that all the daimyo had to spend every other year in Edo, the shoguns capital, and when they were absent, their wives and families had to do so.

Despite such curbs on behaviour, the daimyo remained very powerful and retained a good deal of independence in the administration of their domains, in an arrangement with which successive shoguns appeared content. Apart from the kinds of restrictions discussed above, daimyo had autocratic power in their own territories. Those in western Japan, especially the domains of Choshu, Satsuma, Tosa and Hizen, were notably powerful and were to remain a threat to shogunate power, a threat which was to become reality in the events leading up to the Restoration.4

The perceived internal potential for instability was matched by a belief that foreign influence too could threaten the new regime. Traders and missionaries from Portugal first arrived in Japan at the end of the sixteenth century, to be followed by Spanish friars. In the early years of the Tokugawa, first the Dutch, and then the British arrived. Many Japanese were converted to the Christian religion, and the several trading arrangements seemed to be felicitous, operating to the advantage of all. But from the beginning the situation was potentially explosive. The Europeans brought all their rivalries and hatreds with them. The Portuguese Jesuits and the Spanish friars recreated a microcosm of their deadly sectarian and national antagonism. All nationalities engaged in vicious commercial competition, and in the middle of all the resultant attempts by the foreigners to gain credence at the expense of each other, appeared the remarkable character Will Adams, a shipwrecked English seaman, in the 1980s the subject of a best-selling novel, Shogun by James Clavell. Adams for a variety of reasons, not the least being his considerable knowledge of seamanship, was acceptable to Ieyasu, to their mutual profit.

The Japanese authorities though had never quite come to terms with the behaviour of the foreigners, nor were their suspicions allayed about their motives, or how Japan figured in their plans. At first Nobunaga, the ruler displaced by Hideyoshi was tolerant, and even favourable. Hideyoshi was equally tolerant, except when he issued a decree, never enacted, expelling the missionaries. On another occasion suspecting that the missionaries were the vanguard of an invasion force, he ordered the execution of twenty-six Christians, including six Spaniards in 1597, just before his own death in 1598. leyasu, although he had abdicated in favour of his son only two years after becoming shogun, became more and more concerned about the behaviour and intentions of the Europeans and their increasingly large body of converts. This included an allegation of a plot by both to overthrow the government. In 1612 and 1614 proclamations were made which, on the face of it, were severe. In them Christianity was prohibited, foreign priests were to leave Japan, and churches were to be demolished.

But it was leyasu’s son, Hidetada, upon his father’s death in 1616 who began a serious campaign against Christians, which for the next twenty years included torture, armed struggle, and massacre – a process which produced a home-grown list of martyrs. The shogun-ate was certain that there were clear links between foreigners, especially the Portuguese, missionary activity and subversion. Not only was there ample contemporary evidence that they were right, as in a revolt dominated by Christians at a place called Shimabara in 1637, but Christian missionary work must, intrinsically, be subversive. Much encouragement in repression came from the emperor, and indeed the latter considered that the shogun Iemitsu was not sufficiently determined, a matter to which we will return in a consideration of the role of the imperial institution.

As a consequence of negotiation between emperor and shogun, in 1634 it was ordered that all foreigners were to be expelled, except for a small Dutch trading post, strictly supervised, in Nagasaki. The Japanese people were forbidden to leave the country. Any foreign ships trying to re-establish links were turned away if they were lucky, and in the case of the crew of a Portuguese ship in 1640, executed if they were not. The effects of the isolationist policy were manifold. It effectively eliminated the possible collusion of Japanese dissidents with foreign imperialists, as indeed it was intended it should. But as well as excluding subversive political ideas, all the new industrial innovation and expertise which began to burgeon in Europe soon afterwards were similarly kept out. Storry points out that the policy contained what might have been Japanese expansion in Asia, during the very period when such expansion was being undertaken by nations whose energy and imagination were no greater than that of the Japanese.5 Above all though, events in the nineteenth century were to show that the ambitions of the western nations in Asia were not easily to be contained, and the ‘sacred’ nature of Japanese social religious and political life, much enhanced and emphasised during the Edo Era, was to be one of the battlefields upon which the shogunate which had promulgated exclusion, was to fall.

Since this book focuses upon the nature and evolution of Japanese social structure, institutions and relationships, one aspect of Tokugawa consolidation is of special significance. This is the division of society into hierarchical groups and clans. The latter ‘was the sum of the Japanese soul’. The Japanese subject was ‘throughout his long history “essentially a clansman, with all the group feelings which a clan organization implies”’.6 The clan was firmly located in an area which, because of the relationship of the Japanese to territory, was deeply significant. Indeed, ‘the old domains still live in the Japanese consciousness. In fact, there are some who say the modern prefectures never really took hold’.7 The whole society was strictly hierarchical. Naturally, at the top were the emperor, court aristocracy, shogun and daimyo. The rest, in a pristine, and therefore much oversimplified form were the samurai, the farmers, the artisans and the merchants. Below all of these were minority groups, of which the most important were the outcaste people known at the time as eta. In this account of social history they will receive more discussion than is general in mainstream historical accounts.

Within each of these strata there were s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations and Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Note about names and spellings

- 1. Out of Isolation

- 2. Racism

- 3. Towards a New Japan

- 4. Japan’s Outcastes: Discrimination Then; Discrimination Now

- 5. ‘All Citizens are Soldiers’

- 6. Unfriendly Neighbours: The Peoples of Japan and Korea

- 7. Japanese Tradition and the Curbing of ‘Dangerous Thoughts’

- 8. ‘The Wish of the Dead Child’. Women in Japan: A Wish Denied?

- 9. The Pacific War – ‘hakko ichiu’

- 10.Education: From ‘The Fundamental Character of Our Empire’ to the Cornerstone of Modern Japan

- 11. Swords to Ploughshares: Japan since 1945

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Maps

- Index