![]() PART II COLLECTIVITY, WELFARE, CONSUMPTION

PART II COLLECTIVITY, WELFARE, CONSUMPTION![]()

Chapter 6

The shantytown in Algiers and the colonization of everyday life

Sheila Crane

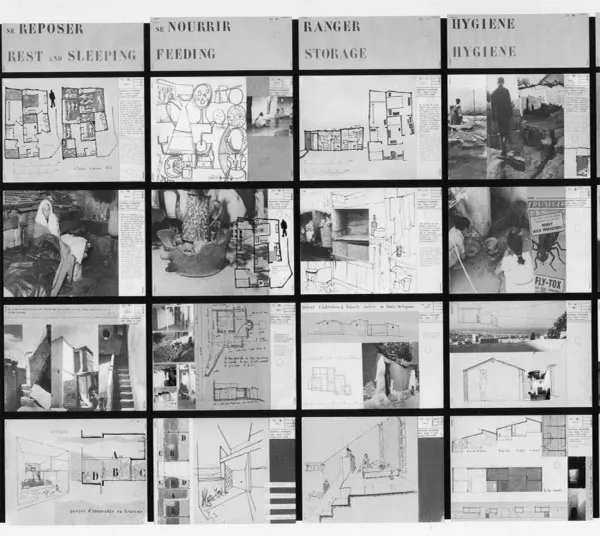

In 1953, a loose affiliation of architects active in Algiers presented detailed studies of la Mahieddine, then the city’s largest bidonville (shantytown), at the ninth meeting of the Congrès internationaux de l’architecture moderne (CIAM, International Congress of Modern Architecture) in Aix-en-Provence (Figure 6.1). Animated by Swiss-born architect Pierre-André Emery, an early collaborator of Le Corbusier and vocal supporter of his urban plan for Algiers (1931–1942), the CIAM-Alger group included Louis Miquel, Jean de Maisonseul, Pierre Bourlier, and Roland Simounet. Together they documented la Mahieddine through architectural drawings, diagrams, photographs, and interviews with residents. These materials, together with visual materials culled from outside sources, were combined in over forty-seven presentation panels, each featuring descriptive captions in French and English. Following the standardized format of the CIAM grid, individual panels were organized into functional categories—including sleeping, eating, storage, and hygiene—to allow ready comparison with other studies prepared for CIAM 9.1 While each panel highlighted discrete observations, the grid aimed to provide a synoptic view of how the bidonville had been shaped by culturally specific patterns of construction and inhabitation.

Figure 6.1 Detail of CIAM-Alger grid, 1953. Fondation Le Corbusier; as reproduced in Max Risselada and Dirk van de Heuvel, eds., Team 10, 1953–81: In Search of a Utopia of the Present (Rotterdam: NAi, 2005).

The CIAM-Alger study—along with the Moroccan CIAM group, Groupe d’architectes modernes marocains (GAMMA, Modern Moroccan Architects’ Group), whose study of bidonvilles and traditional settlement patterns in Morocco was also presented at CIAM 9—has been understood to mark an epistemological shift in modern architectural discourse. In her study of the CIAM-Alger grid, Zeynep Çelik described it as an early instance of architects adopting the tools of anthropology to trace “the imperative role everyday life played in housing design.”2 Above all, she praised the architects’ sustained attention to inhabitants’ use of space, while emphasizing that these studies significantly influenced Roland Simounet’s subsequent work. Similarly, Tom Avermaete argued that GAMMA architects positioned themselves as “epistemologists of the everyday.”3 In effect, these architects were simultaneously participants in, producers of knowledge about, and designers of everyday spatial practices. Avermaete suggests that these divergent vantage points together provided an effective means of critically engaging postwar processes of “French modernization.”4 More recently, Avermaete returned to both GAMMA and CIAM-Alger grids to emphasize their intersecting aims of critiquing the socio-spatial effects of colonialism, celebrating everyday dwelling processes, and advancing concrete architectural solutions. In Avermaete’s view, these multiple perspectives represent “a new viewpoint which conceives the built environment as result, frame, and substance of socio-spatial practice.”5 The epistemological shift Çelik and Avermaete identify thus turned on the embrace of the everyday as a terrain of architectural investigation and the concomitant emergence of the user as a subject of analysis.

For both authors, this ethnographic turn was generative of new architectural knowledge and fundamental critiques of CIAM principles. However, in the interest of situating these studies of the bidonville in relation to modern architectural discourse, Çelik and Avermaete mention but do not pursue their connection to the longer history of ethnographic studies of indigenous dwelling practices in Algeria and the colonial regime’s use of such projects as explicitly biopolitical tools. At the very moment the CIAM-Alger study was undertaken, the colonial administration was formulating new housing policies focused on the bidonville in a last-ditch effort to quell increasingly strident calls for Algeria’s independence. The implications of these events and of earlier colonial uses of anthropology for these architects’ ethnographic turn are worthy of closer examination. Inspired in part by his work in the bidonvilles of Algiers beginning in 1955, Pierre Bourdieu emphasized the gap that always exists between ethnographers and their subjects of study. In the context of colonization, this relationship is politicized to an extreme, given that, as Michel Leiris observed, “the ethnographer, by virtue of his membership in the colonizing society, bears the weight of the original sin of colonialism.” 6 While Bourdieu resisted the idea that any social scientist—even one studying the social group to which she belonged—could overcome this distance, he insisted on the exceptional pressures of complicity produced by the colonial situation.

Roland Simounet’s work offers a productive lens through which to trace these dynamics. The methodology he and his colleagues developed in the bidonville in Algiers directly informed two of his subsequent projects: Djenan el Hasan, a housing development in Algiers intended to temporarily re-house residents of the bidonville before they accessed more permanent accommodations, and his proposed renovation in the early 1980s of Logis d’Anne, a temporary resettlement project near Aix-en-Provence created for Algerian immigrants shortly after Algeria officially declared its independence in 1962. In translating lessons from the bidonville in Algiers in 1953 into emergency housing there three years later and into a crumbling refugee camp in France three decades later, Simounet negotiated the shifting positions of insider and outsider, participant observer and designer. In the case of the Logis d’Anne renovation, this ambiguity was explicitly acknowledged, even as Simounet’s investments in his own Algerian origins re-emerged with new force.

Discovering the Bidonville: CIAM-Alger, 1953

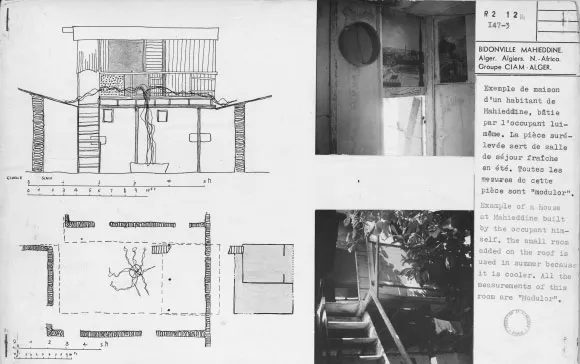

The CIAM-Alger study was an explicitly collaborative project, drawing especially on the contributions of Emery, Miquel, and Simounet. Simounet, the youngest member of the group and, like Miquel and de Maisonseul, a native of French Algeria, was responsible for numerous on-site drawings and interviews of la Mahieddine’s inhabitants.7 This informal settlement had developed incrementally on formerly expansive gardens surrounding a villa of the same name, one of numerous such structures constructed on the outskirts of Algiers during the Ottoman period. An initial cluster of dwellings eventually swelled into a dense conglomeration of between 7,400 and 10,000 residents, featuring a mosque, a school, and an extensive commercial street.8 While the settlement’s overall organization was sketched in broad outlines, the majority of the CIAM-Alger grid focused on its dwellings. One such panel depicted a typical house in plan, elevation, and two photographs, in order to highlight how new additions responded to the household’s changing needs (Figure 6.2). The drawings emphasized a tree that formed the dwelling’s symbolic center, defining both building and open courtyard, while the text described the second-story addition as an organic accretion. Such spontaneous acts of constructive adaptation were presented as the bidonville’s primary structuring logic.

Figure 6.2 CIAM-Alger presentation panel, 1953: typical dwelling. Fondation Le Corbusier, R2-12-14.

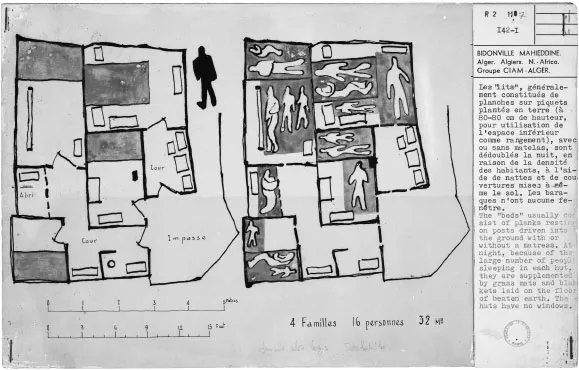

Figure 6.3 CIAM-Alger presentation panel, 1953: day/night diagram plan. Fondation Le Corbusier, R2-11-7.

Among the most striking documents featured in the CIAM-Alger grid were four plans diagramming patterns of occupation over the course of a day. As a series, they revealed how the same group of structures was transformed through daily activities, whether evidenced in how rooms were vacated or occupied from day to night (Figure 6.3), or in the way food preparation mapped these same spaces differently. Whereas the CIAM grid defined “use” in terms of functional categories, the diagram plans communicated a more nuanced understanding of dwelling as process, through which layered spatial experiences unfolded over time. Another diagram of storage areas drew attention to how inhabitants had creatively harnessed minimal spaces for maximal occupation. The economical use of space demonstrated in these multi-functional rooms was facilitated, in the eyes of CIAM-Alger architects, by the strictly utilitarian character of the few possessions found there. In turn, photographs and drawings invested commonplace objects with special significance by depicting them as material traces of how a rural Algerian habitat had found its way to the city.

The tools of documentation that Simounet and his colleagues employed echoed those of colonial ethnography, within which indigenous dwellings occupied a privileged position. Beginning with the bureaux arabes, a network of colonial agents established in the 1840s to gather information about local populations in far-flung rural areas, participant observation and “surveillance documentation” had long been harnessed to assert French authority. Cultural knowledge about Algerians produced through ethnographic study thus played an instrumental role in shaping colonial policy.9 By the 1920s, the Algerian house had become the subject of sustained typological analysis in accounts that often reinforced the prevailing dichotomy between sedentary mountain-dwelling Berber or Kabyle populations on the one hand and nomadic plain-dwelling Arab populations on the other. Publications like Augustin Bernard’s 1921 Enquête sur l’habitation rurale des indigènes d’Algérie (Survey of the Rural Dwellings of Algeria’s Indigenous Populations) reinforced the belief that Algerian culture was fundamentally rural and defined by static social structures.10 While Bernard acknowledged that rural houses had evolved in their form and uses, his account, and others like it, emphasized above all those artifacts of dwelling that could be recuperated as evidence of timeless traditions understood to be the very essence of Algerian identity.11

By contrast, Simounet and his colleagues celebrated traces of architectural improvisation in la Mahieddine and the dynamism that shaped ever-evolving auto-constructions there. Bidonv...