![]()

Chapter 1

Supportive Relationships in Shared Housing

Jon Pynoos

Lisa Hamburger

Arlyne June

Jon Pynoos, PhD, is Associate Professor of Gerontology and Urban Planning and Director, Program in Policy and Services Research, Andrus Gerontology Center, University of Southern California, University Park, MC 0191, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0191.

Lisa Hamburger, BS, is Research Assistant, Dual Masters Degree Candidate in Urban Planning and Gerontology, University of Southern California.

Arlyne June, MA, is Executive Director, Project Match, 1671 Park Avenue, San Jose, CA 95126.

Appreciation is extended to Jim Corcoran who conducted the telephone interviews and Mary Jackson who assisted in the data analysis.

Summary. This study surveyed a random sample of 144 house sharers of one of the country’s oldest matching programs to investigate which types of persons house share, reasons that people choose house sharing, the types of assistance house sharers need and provide for each other and the types of housing sharing relationships that exist. It found that primary reasons for sharing were financial (44%), companionship (21%), and help in home and health care (19%). Almost one-third of housesharers were frail and while they received a significant amount of assistance from their partners in household tasks, not all of them were in matches in which services were provided or exchanged. And, contrary to other research that suggests matches are not conducive to intimacy, almost half the sample indicated moderate to strong levels of friendship as well as willingness to confide in their partners on personal matters.

The availability of affordable and supportive housing is an increasing concern for frail older persons. Solutions such as public housing have been curtailed and programs such as congregate housing have never gone beyond the demonstration phase. The federal government is now promoting community-based alternatives intended to make better use of existing resources. In response, a spectrum of services and support system networks has been developed to enhance the present housing environment of the elderly and, as a consequence, improve their well-being. One such system is shared housing.

Shared housing programs attempt to match residents, known as providers, who have extra living space in their apartment or home with unrelated individuals, known as seekers, including couples or single parents with children. In contrast to most senior citizen services which are delivered to the home or provided at community focal points, home-sharing programs are implemented in the home through the emerging relationship between the matched sharers: provider and seeker (Schreter, 1984). As such, the arrangement is designed and managed by and for the sharers, with minimum agency intervention. The unique package of services each arrangement affords may provide for a wide spectrum of needs (e.g., from simply sharing housing costs to providing household services for those with functional limitations). Such arrangements may create new roles for elderly participants. The nature of the relationship can positively effect the ability of frail older persons to remain in the least restrictive living environment. In addition, housesharing can provide financial assistance and companionship in a familiar and comfortable setting.

In spite of the prominence awarded to shared housing, very little systematic research has been done on the topic. Of those studies which have sought to measure various characteristics of home-sharing programs, sample sizes have generally been small, making it difficult to perform tests of statistical significance. The present study examines the homesharing arrangements of Project MATCH, to begin to assess the success of such arrangements in meeting the needs and expectations of those involved. Among the issues examined are:

1. the demographic characteristics of persons who participate in homesharing programs,

2. the household and daily maintenance service needs which can be met by homesharing,

3. the interpersonal factors and environmental conditions which can contribute to the satisfaction or lead to the dissolution of matches,

4. the level of intimacy which can develop between partners and what accounts for differences, and

5. appropriate basis by which to classify matches.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data Source

Data for this study is based on the experiences of 144 past and continuing participants of Project MATCH, a homesharing program based in San Jose, California. The program, began in 1977, is the oldest housesharing service in the United States. It is administered by a private non-profit agency that arranges potential matches for seniors and other adult residents of the Santa Clara County. In 1981, the program was awarded the affordable housing award from the State of California. In its first one and one-half years, Project MATCH placed 400 seniors. By June 1986, almost 7,009 persons had been “matched.” The project arranged sharing for 1,049 persons during 1982, providing a large subject pool available for analysis. The program has expanded to include other age groups and thus allow for intergenerational matches (where partners’ ages differ by more than ten years).

Project MATCH is based primarily on a hybrid referral/counseling model (Dobkin, 1983). Potential clients call the agency and make an appointment for a personal interview with a housing counselor. At the time of the interview, a client intake, participation agreement and consent form are used as a basis to gather information. During the intake/screening period, clients are advised in terms of what to realistically expect from a shared housing arrangement. Counselors then search for referrals with complementary needs and compatible preferences. Currently, there is no fee to clients, although small donations ($5 for providers and $3 for seekers) are requested when possible.

Once the clients are interviewed and potential matches have been found, referrals are made by contacting each client by telephone and directing them to arrange a meeting time with their potential partner. After this initial meeting between potential partners, Project MATCH contacts each client to ascertain their respective reaction. If the match is arranged, a match certificate is signed. Participants are assisted in setting up rules, contracts, and written agreements if they choose. Follow up is provided after one, three, and six months from the time the arrangement is made, and then every six months, up to two years. For matches providing live-in service arrangements, follow up is done every month.

Data Collection

The sample group was selected randomly from the project’s file of matches arranged between July 1, 1982 and November, 1983. In addition, seven matches were selected from the prior year for qualitative purposes. Since only providers’ addresses are maintained in the roster and seekers who were no longer matched seldom left a forwarding address, it was not possible to locate most seekers once they left the homesharing project. As a consequence, 74 percent (107) of the 144 respondents were providers and 26 percent were seekers.

Information was gathered through the administration of a 28 page questionnaire over the telephone. Questions focused on the respondents’ characteristics and the microlevel of interaction during the match. In addition, respondents were asked corresponding details concerning their partners. Standard questions were asked concerning health and mobility. Portions of several surveys were left incomplete as a result of respondents inability or refusal to answer questions.

SURVEY RESULTS

Characteristics of Sharers

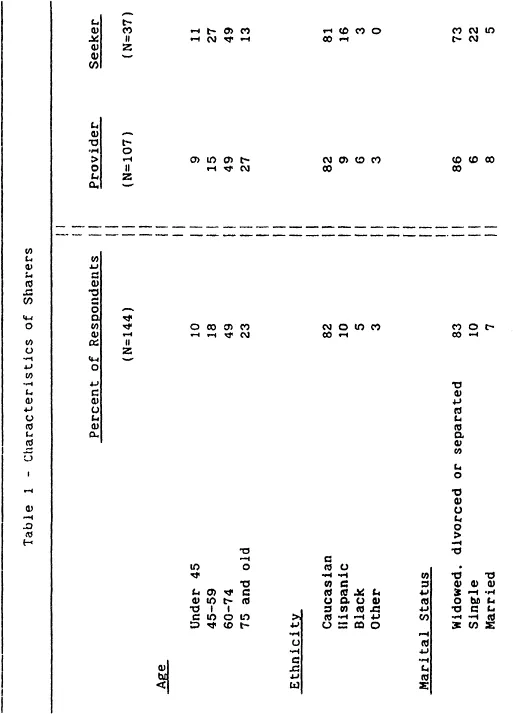

Among those interviewed, 82 percent of all sharers, both providers and seekers, were women. Other studies (Howe, Robins and Jaffe, 1984; Pritchard, 1983) have supported this finding that home-sharing programs disproportionately attract women. By contrast, the age composition varies significantly among different programs depending on the target population, location and housing market. The sample studied here ranged in age from 24 to 96 years, with an average age of 65 years. Providers tended to be older than seekers; 70% of providers were over age 60 as compared to only 59% of the seekers (see Table 1).

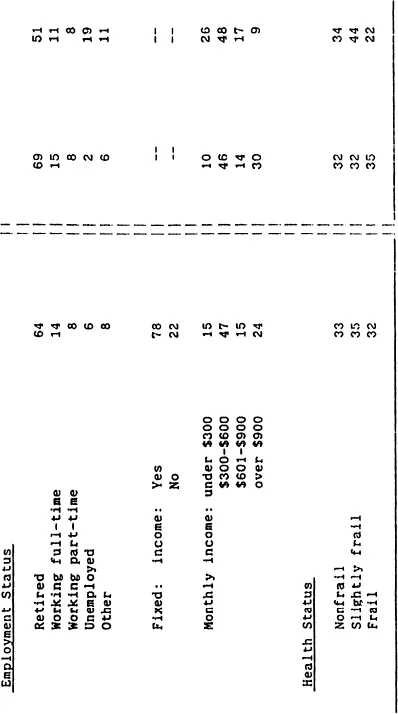

Respondents were also questioned about their ethnicity, marital status, employment status, income and health status. The majority of those sampled were Caucasian. Expectedly, widowers and divorcees were more often providers than seekers, while singles showed the reverse tendency. Also as expected, given the age of the respondents, most were retired: almost 70% of providers and 51% of seekers. Many other seekers appeared to be in transitory roles, 19% were unemployed and 5% were students. Seventy-eight percent of respondents were living on fixed incomes and over half (62%) of the subjects had monthly incomes under $600.

The health status of subjects was defined by a composite score based on: (1) the number of doctor visits in the last year, (2) the number of days spent in the hospital in the last year, (3) self-appraised health status (poor to excellent), (4) the extent to which health problems were reported to interfere with “doing things,” and (5) number of ambulation limitations including walking, climbing stairs, boarding a bus, and using a walker or wheelchair. These five variables were entered into a factor analysis (see Table 2) to test for internal validity and to generate factor scores. The resulting factor loading revealed a high level of internal validity, and therefore supported the use of the five variables.

Factor scores were then generated and the resulting range of scores was divided into thirds to define respondents as either non-frail, slightly frail or frail. The respondents falling into the frail category exhibited more than three ambulatory problems (55% of the frail had four such problems), as compared with 0 to 1 reported for the slightly frail. The non-frail respondents reported no ambulatory problems. As expected, due to the physical requirements of seeking housing, a higher proportion of providers (35%) were frail as compared to seekers (22%).

Table 2 - Factor Analysis for Determining Frailty Index

ITEM | FACTOR LOADING |

Doctors visit | 0.589 |

Hospital days | 0.638 |

Self-reported health | 0.685 |

Health interferes | 0.901 |

with doing things | |

Ambulation limitations | 0.859 |

Eigenvalue = 2.77 | |

|

Nature of Arrangements

Demographic Characteristics of Matches

With regard to gender and ethnicity, individuals tended to be matched with partners with characteristics similar to their own. Sixty-one percent of the matches were male-male or female-female. Similarly, 83% of the matches involved individuals of the same ethnic/racial background. In contrast, intergenerational matches, where the age of the partners differed by more than 10 years, were frequent (60% of the matches could be defined as intergenerational.)

Motivation for Sharing

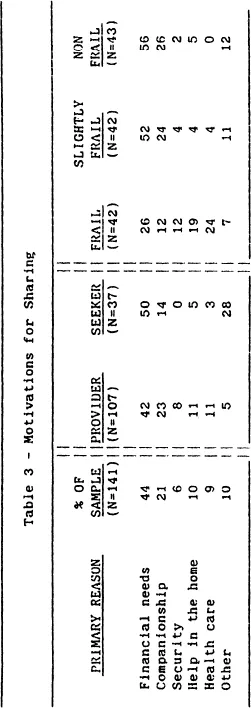

Overall, the primary reasons considered by both providers and seekers in deciding to homeshare were financial need (44%) and companionship (21%) (see Table 3). Pritchard (1983) and McConnell and Usher (1980) also identified these two factors as the most common in motivating people to houseshare. Frail subjects were more apt to share because of health care needs, help in the home or security, rather than companionship reasons.

Housing Type and Facilities Shared

One reason homesharing has recently gained attention is the increased use of available space that this housing alternative capitalizes on. It therefore was anticipated that providers were more apt to share because they had extra space in their residence. The data however revealed that only 20% of respondents identified their house as “too big.” Sixty-four percent of the respondents were sharing a single family home. In 98% of the matches the residence contained at least two bedrooms; bedrooms were seldom a shared space. Communal spaces most often shared included kitchen facilities (95%), entrance (94%), living room (93%), and laundry facilities (92%). Bathrooms were shared in 53% of the matches.

Financial Arrangements

Four types of financial arrangements were established between sharers, including: (1) seeker pays rent only (61%), (2) seeker pays rent and provides service (1...