- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Individual Differences in Second Language Learning

About this book

Understanding the way in which learners differ from one another is of fundamental concern to those involved in second-language acquisition, either as researchers or teachers. This account is the first to review at book length the important research into differences, considering matters such as aptitude, motivation, learner strategies, personality and interaction between learner characteristics and types of instruction.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Theoretical foundations

In the past fifteen to twenty years, the field of second language acquisition has grown enormously, with the quantity of published research increasing annually. As a result, the accumulation of data is expanding our understanding of the complexity and range of the task of the second language learner, and so providing a sounder basis for theory construction. It is striking, however, that the main thrust of this research has been towards establishing how learners are similar, and what processes of learning are universal. Studies of universal grammar or of acquisitional sequences, or of error types, are good examples of this. Such studies are not misguided - in fact, it is research activity in areas such as those just mentioned which has brought about the increased impact of SLA research. There are, however, alternative research traditions, and it is one of these, the study of the differences between learners, that will be the major focus for this book.

Although the contrast between the study of common processes and the study of individual differences (IDs) is well established in other disciplines, such as psychology, this is not the case in second language learning, where a robust ID tradition is somewhat lacking. It is the aim of this book to review such ID research as exists, and to demonstrate its relevance to other aspects of SLA, so that its influence may be all the greater in the future. Chapters will try to set out the major areas in which language learners differ, covering areas such as language aptitude, motivation and cognitive style, and of individual control over learning (strategic influences). These chapters represent the main part of the book, since there is relevant (and growing) research in each area. In addition, there is coverage of the small but important area of interaction- effects, of studies which assume individual differences but which then go on to examine whether particular types of individual do well when matched with particular instructional conditions. Before we approach these substantive areas though, we need, at the outset, to consider what sort of theoretical framework is appropriate for the study of Individual Differences.

Models of SLA

Model-making has been a growth area in second language learning in recent years. We shall consider four contemporary models in this chapter, and evaluate their usefulness for ID research.

The ‘Language Two’ or ‘Monitor’ model:

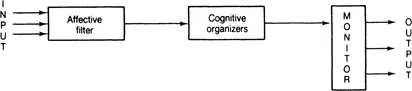

Dulay, Burt and Krashen (1982) propose the following model:

Figure 1.1: The Dulay-Burt-Krashen model

Building on this work, Krashen (1985) links the model to five hypotheses for SLA:

1The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis

2The Natural Sequence Hypothesis

3The Monitor Hypothesis

4The Affective Filter Hypothesis

5The Comprehensible Input Hypothesis

The ‘Monitor Model’ outlined above will not be discussed extensively here (see McLaughlin 1987 for a very thorough evaluation) but only as it relates to individual differences. Krashen is really proposing three general areas where variation is important. First, there is the quantity of comprehensible input. Progress is seen to be a function of the amount of such input as is available. This source of variation is outside the learner, and indeed, environmentally determined. The second source of variation is the Affective Filter. Krashen suggests that this may be raised or lowered, i.e. the learner’s openness or lack of anxiety may vary, and that the ‘position’ of the filter will influence how much input is ‘let through’. This is, potentially, an important ID involving the learner. Finally, there is variability in Monitor use. Krashen speaks of Monitor ‘over-users’ (those whose constant striving for correctness inhibits output), and ‘under-users’, (those whose lack of concern with correctness leads to garrulous but less grammatical performance).

In other words, several components in the model could be the source of individual differences. However, the central component, the Cognitive Organizers, is not so affected. Here, where actual ‘acquisition’ takes place, where Natural Sequences are preordained, where learning is irrelevant, there is only room for universal processes and lack of individual differences. The assumption is being made that, given comparable input, all learners will process the data in the same way and at the same speed. How much input gets through to this part of the model may vary, but the processes that operate on the input will be the same.

In fact, even those components of the Monitor Model which seem to be the source of IDs are disappointing when one examines them in more detail. The Monitor itself, as we have seen, appears to allow variable performance. However, Skehan (1984a) has criticized the status of the Monitor in relation to the rest of the model, suggesting that while it is concerned with on-the-spot performance, the rest of the model is concerned with the process of learning over extended time. This separation reflects the acquisition-learning distinction (Krashen 1981) in that Monitoring, being the product of learning, does not influence acquisition, i.e. the process of change. But the separation, and the postulated imperviousness of acquisition to effects of learning, means that the IDs that may exist in amount of Monitor use (i.e. ‘over’ and ‘under’ users) do not connect up with other, more central aspects of the model. To allow this to happen learning would be having an indirect effect, and the model would be self-contradictory. Since such an influence is then not permissible, IDs become trivial.

The discussion of differences elsewhere is similarly problematic. As far as both comprehensible input and affective filter variation are concerned McLaughlin (1987) has severely criticized Krashen for vagueness as to what is actually being varied. McLaughlin (1987) points out that Krashen does not explain how comprehensible input can be specified without circularity, and that no convincing account is given of how the Affective Filter changes level and on what basis it can be selective in its operation. Hence the impression we are left with is that labels have been attached to areas where it is known there is variation, but that the explanation of the variation is not advanced at all.

The ‘Good Language Learner’ model:

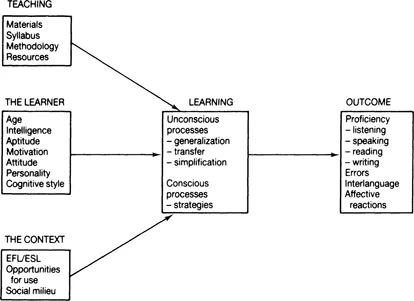

By way of contrast, we will next consider a model proposed by Naiman, Frohlich, Todesco, and Stern (1978) as part of the ‘Good Language Learner’ (GLL) study. The term ‘model’ is misleading, since what is really being proposed is only a taxonomy or listing. Still, even at this level, what Naiman etal. (1978) describe is interesting.

The diagram consists of five boxes, representing classes of variable in language learning. These may be divided into three independent (causative) variables and two dependent (caused) variables. The independent variables, teaching, the learner, and the context, themselves have to be subdivided further, since they are each composites of many independent influences. Hence the need to specify the quality of the instruction, the quantity of resources, intelligence, personality, opportunities for informal target-language use, etc. The dependent variables also need some further subdivision. Outcome, the ultimate ‘caused’ variable, is seen to consist not merely of proficiency measures, but also of more qualitative aspects of performance, i.e. errors, as well as affective reactions to learning, the language, the people, and the culture concerned. The Learning box, is, perhaps, the most complex of all. It consists of two rather different things. On the one hand, there is learning, the process of developing one’s competence in the target language, with the focus here being on something like Selinker’s five strategies for inter language (Selinker 1972). On the other, there are learner strategies, which imply some degree of learner control and of distance from the actual process of learning.

Figure 1.2: The good language-learner model

The model or taxonomy shown in Figure 1.2 is essentially atheoretical, and explains very little. However it does have three advantages. First, it allows us to see the range of potential influences on language learning success. In this way, it demonstrates what varied influences there are: how difficult it is to study just one of them in isolation; how they may be classified; and what range of variables needs to be controlled in research studies. A second advantage of such a taxonomy is that, although list-based, it encourages quantification of the different influences. It implies that one should be able to establish how strongly aptitude or classroom organization, for example, influence the outcome of language learning: it is not enough to demonstrate ‘an effect’ - one must also assess how important the effect is. Finally, the GLL model offers some scope for conceptualizing interaction effects. For example, one could ask whether personality and methodology interact, with (say) extrovert learners doing particularly well in communicatively oriented classrooms, introverts doing well in teacherled classrooms, and each learner group doing poorly when exposed to the inappropriate methodology. Since the model attempts to list the different potential influences on language learning, one has a clearer idea of where to look for interactions.

The two models outlined so far, Krashen’s (Figure 1.1) and the Good Language Learner Model, (Figure 1.2) provide an interesting contrast in theory construction. McLaughlin (1987) makes a distinction between hierarchical and concatenated theories. Similarly Long ( 1985) and Larsen-Freeman and Long (forthcoming) distinguish between a theory-then- research approach compared to research-then-theory. The first alternative, in either case, involves the elaboration of a theory or model which makes predictions and which has explanatory power. It is (or at least should be), falsifiable, in that the predictions which are made must be capable of empirical test. The second approach suggests the identification of an area that looks promising for research and which is relatively circumscribed. The researcher then attempts to collect ‘facts’ in the chosen area, facts which may form a part of subsequent hierarchical theorizing.

In the present case the Monitor model would certainly be seen as a hierarchical model which operates from premises, makes predictions, and inter-relates the parts of the model in a logical system. In contrast, the Naiman model is very much in the concatenated or research-then-theory approach, providing a rudimentary categorization of relevant variables and then implying a research programme which accumulates quantitative information on the individual variables so categorized. It should enable us to reach a ‘take-off’ point from which it is feasible to produce more effective hierarchical theories. This is because we will have a better sight of where we are going; are less likely to ignore important data; and will have a better understanding of the scale of the problem. Certainly ID research can be conceived of much more easily within the concatenated, or research-then-theory perspective, and so the GLL model seems more appropriate as a-guiding framework. This issue, though, will be returned to in Chapter 8, and pursued in the light of the intervening chapters, in which the respective strengths and weaknesses of the two approaches to theory-building will be assessed. For the present, though, two more models need to be discussed.

The Carroll model of school learning: an interactional model:

A third model to be considered is that proposed by J .B. Carroll in the early 1960s (Carroll 1965). The model was put forward to account for school learning and as a result focused on a limited set of variables. It is proposed here, however, that the model could be generalized to incorporate other variables and more complex situations. It is important that applied linguistics researchers do this, since it is argued that what are required most urgently in second language learning are models which allow both instructional (i.e. treatment) factors and individual difference variables to operate simultaneously.

The model, then, starts by considering two major classes of variable - instructional factors and individual difference factors. These are sub-categorized as follows:

| Instructional factors – time – instructional excellence | Instructional factors – general intelligence – aptitude – motivation |

The first instructional factor is time, and it is postulated that progress is a function of amount of time spent learning: the greater the time, the greater the learning. The second instructional factor is excellence of instruction. Clearly, defining instructional excellence is something of a problem, and it is striking what changes have taken place since the publication of Carroll’s model in terms of what conventional wisdom now regards as good teaching. The growing field of classroom research is an attempt to at least describe classroom events and processes. For the present we will simply assume that differences in instructional effectiveness do exist, and have a place in the model.

The first of the three individual difference variables is intelligence. Carroll conceived of this as the learner’s capacity to understand instruction, and to understand what is required of him in the learning situation. Intelligence, that is, is conceived of as a sort of efficiency factor, a talent for not getting sidetracked or wasting one’s efforts. Aptitude, and in this case, foreign language aptitude, is seen as a generalized capacity to learn languages which is separate from intelligence, and which consists of several sub-components - associative memory, inductive language learning ability, grammatical sensitivity, and phonemic coding ability (see Chapter 3). Finally, motivation is seen as the individual’s need to study the language in question and his willingness to persevere and overcome obstacles.

In a sense, therefore, Carroll’s model is only a subset of the Naiman model, in that it includes some instructional and learner variables, but leaves out others, and it leaves out altogether the context of learning, the process of learning, and learning strategies. Even so, it is of interest because it attempts to be more than a static listing of influences. What Carroll attempts to do is to specify the nature of the interaction between the variables, and to indicate how differences in one variable will constrain the operation of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Theoretical foundations

- 2 Methodological considerations

- 3 Language aptitude

- 4 Motivation

- 5 Language learning strategies

- 6 Additional cognitive and affective influences on language learning

- 7 Interactions

- 8 Conclusions and implications

- References

- Indices

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Individual Differences in Second Language Learning by Peter Skehan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.