![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Arts organizations need revenue. Museums, performing arts organizations, and festivals need funds to be able to meet their expenses. These funds can come from grants from public sector arts councils or private foundations, from donations by individuals and businesses, from the sale of advertising, or from corporate sponsorships. This book is about one source of revenue in particular: prices charged to members of the audience. The goal is to give arts managers tools they can apply in setting prices strategically, and in so doing further the goals of their organization more effectively, whether it is in the commercial, nonprofit, or public sector. Students of arts management should find this a useful introduction to a topic of very practical import in their future careers. Those already working in the field will hopefully gain some new perspectives on price-setting. Although this is a book about pricing in the arts, it draws freely from other fields – news media, restaurants, hotels, airlines, clothing, and electronics, for example – that provide relevant insights for the cultural sector.

The approach in this book is to provide a systematic way of thinking about pricing in all its aspects. It is not written as a “cookbook,” with a set of recipes for dealing with different pricing issues, but rather it is designed to give the reader a method for thinking strategically about pricing. It will show that a common framework can be used to deal with such seemingly disparate questions as: How much of a discount ought to be given to students? Is it better to have a low admission fee with additional charges for exhibitions within the venue, or a higher admission fee with everything free once inside? How does one choose a partner organization with which to offer a joint discount? How much should a subscription cost relative to the cost of a single show? Of course, practicing arts managers have faced the task of having to answer these questions, and might finish this book by thinking, “well, that’s just common sense!” But even in that case, if the book provides confirmation of why their successful practices have been common sense, there is a value in that. If we were to visit a local billiard parlor, it would likely (although not certainly) be the case that the best player would not be able to explain the laws of physics that governed the choice and technique of each shot; the player simply “knows” what to do. Here is hoping that even a very successful manager, like a very successful billiard player, can learn something from a systematic analysis of the decisions they make.

There is a deep, and lively, research literature on pricing strategy. But it is, for the most part, inaccessible to those lacking a post-graduate degree in economics, being highly mathematical, and relying upon a comprehensive understanding of microeconomic theory. In the pages that follow I will draw upon the insights from this body of research, but I will present it without presuming any background knowledge of theory or advanced mathematical techniques. As this is meant to be a practical guide, the text will not be laden with footnotes, although I will conclude each chapter with a list of sources.

Are there not software programs that can solve the pricing problem for you? Indeed, on the market there are programs and services that can track ticket sales of all types for past and current events, and these are very helpful to managers in understanding the patterns of customer demand. As we will see, knowing these patterns will be very helpful in making decisions on prices. But although the software programs provide useful information, they will not tell you what prices to charge. Price-setting remains an art, and this book is meant to develop your skills in that art.

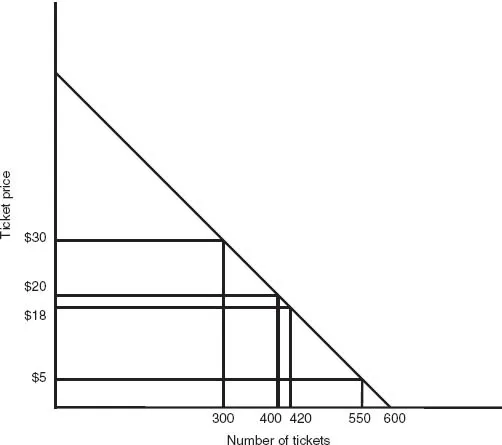

Strategic pricing begins with one single insight: the customers to whom you might sell a ticket to your event differ in the maximum amount they would be willing to pay. To illustrate, consider the following example. Figure 1.1 presents the demand curve for tickets for an outdoor performance by a touring symphony orchestra, on a Saturday afternoon in June. There is to be only one performance, and all tickets are for general admission. The demand curve presents the organizer’s best estimate, based on past experience of similar events, for the expected number of tickets that would be sold at various prices. At a price of $30, we expect 300 tickets to sell, at a price of $20, we expect 400 tickets to sell, and at a price of $18, we expect demand to be 420 tickets. At a price of just $5, demand would be 550 tickets, and if the event were free, with a price of $0, 600 people would attend. Although in this example the demand curve appears as a straight line, in other cases it might be curved; it depends on this particular market. In every case, however, we expect it to be downward sloping: the higher the price, the fewer tickets we will sell, an expectation that economists have elevated to the status of the law of demand.

FIGURE 1.1 Demand curve for a symphony concert

Following Chapter 2, in which we introduce some useful terms and concepts, in Chapter 3 we consider the case of the organizer for this performance who has just one price to choose: general admission. We will derive a rule for setting this single price in a way that maximizes the profits (revenues minus costs) from the event. This rule will be important as we proceed to more complex pricing problems.

Note something about the demand curve from Figure 1.1. According to the figure, there are 300 people who are willing to pay at least $30 to attend the performance. There are another 100 people who are willing to pay at least $20, but not as much as $30, for the event. The term we will use to denote the maximum that an individual would be willing to pay for admission is reservation price. There are 20 people whose reservation price is something between $18 and $20. And there are 50 people whose reservation price is between $0 and $5. If this event involves just a single, general admission price, then those with a reservation price at that amount or higher will attend, and those with a reservation price lower than the announced price will not attend.

The essence of strategic pricing is the recognition that different members of your potential audience have different reservation prices, and that you can increase net profits by segmenting your audience according to what they are willing to pay, charging a higher price to those with higher reservation prices, and a lower price to those with lower reservation prices. Economists refer to this kind of audience segmentation as price discrimination, which is perhaps unfortunate, as the word “discrimination” can carry negative undertones, and hints at the notion that it works to the disadvantage of consumers. But it will be shown that some consumers can benefit from the practice. Chapters 4 through 8 explore various, and not mutually exclusive, means of price discrimination.

Chapter 4 considers what is known as direct price discrimination, where the audience is segmented into easily identified and verifiable groups, to whom different prices are charged. A common example of this is concessionary admission fees for students, seniors, or the unemployed. Arts presenters can take what knowledge they have of the patterns of reservation prices within each group and set differential prices.

Chapters 5 through 8 involve indirect price discrimination. In this case, we know something about patterns of reservation prices, but not enough to allow potential customers to be sorted into identifiable groups. With indirect price discrimination, each potential customer is offered a range of options – a menu – from which to choose. Audience members effectively sort themselves according to their reservation prices.

The first application of indirect price discrimination, presented in Chapter 5, is two-part pricing. To take a canonical example, suppose you are setting prices for an amusement park and must choose, first, an admission fee, and, second, a price for each ride within the park. Other things being equal, the higher the price per ride, the lower the amount a customer would be willing to pay as an admission fee. What is the best combination of admission fee and price per ride? It turns out that the best combination depends upon what we think we know about the different preferences embodied in those with high and low reservation prices. More specifically, we can imagine that some visitors simply enjoy the experience of visiting the amusement park, but will only be interested in taking part in a few rides. Other visitors are there only for the rides, it is their primary motivation for attending. If we learn that high reservation price visitors tend to fall into one of these two categories, that information can be exploited in the choice of how to balance admission fees and ride prices. The chapter will consider applications of this technique in the arts.

Chapter 6 will examine pricing when the presenter is able to offer varying quality of experience. Performing arts venues set different prices for different seats or for different performance times; publishers set different prices for hard covers, paperbacks, and e-books; record companies produce ordinary and deluxe versions of CDs. It is no surprise that lower quality versions sell for lower prices. But how big should the price differential be? And what choices are involved in creating the quality differentials in the first place?

In Chapter 7 we consider pricing over varying quantities of offerings. Examples include subscription series and memberships, and we will consider how to set price differentials between single and multiple visits, or even whether customers ought to have a choice at all. Consider that my cable television provider does not allow me to purchase just one channel to view, but instead I must purchase a bundle of channels. Why do they insist upon this, and what can arts managers learn from the example?

Chapter 8 looks at the practice of tied sales, where customers receive a discount if they purchase different goods as a package. Theatre patrons in London are offered deals that combine a pair of tickets with a dinner from a (limited) choice of restaurants. What are the advantages to the theatre company in making such an offer? If the motive is to make attending the theatre more attractive, why not simply lower the price of tickets? We will look at cases where tied sales make sense, and how best to choose the package of offerings.

Again, we will see that two-part pricing, quality differentials, bundles, and tied sales are all means of separating those potential customers with high reservation prices from the rest, and finding ways to draw more revenue from those customers than it is possible to obtain from those with lower reservation prices. I will note at the outset that segmenting customers by their willingness to pay is not a way of deceiving patrons, or of tricking them, or of exploiting patterns of irrationality. While these practices are not unheard of within the economy, the strategic pricing techniques covered in this book are respectful of the intelligence of the arts consumer and advocate transparency in what is put before them.

Chapter 9 covers the topic of changing the price of a specific event over time, whether the change is announced to patrons well in advance (for example, when it is made clear that tickets purchased on the day of the event will cost more), or when the change, if any, is not predictable, and is based upon the revealed demand for tickets after they have gone on sale; this is the practice known as dynamic pricing. Dynamic pricing is familiar to us from the hotel and airline sectors, but has recently come to be used in some arts and professional sports organizations. In this chapter the technique for applying dynamic pricing will be explained, along with its pitfalls; it remains unclear whether the practice will become widely adopted.

Finally, Chapter 10 looks at pricing when social mission would dictate a departure from profit-maximizing strategies. Many readers of this book will either be working or intend to work in the nonprofit or public sector. I placed this topic at the end of the book because I believe it is important for arts managers in organizations with a nonprofit mission to understand the techniques of strategic pricing first. Only then is it possible to systematically consider departures from these rules in order to further the mission of the organization. It is common for nonprofit arts organizations to employ all of the techniques of strategic pricing covered in this book, and a better understanding of pricing methods can assist nonprofit arts managers in determining the situations where price adjustments are warranted.

I have taught students the analysis presented in this book for a number of years now. The students in our program typically arrive with a background in music or theatre or visual arts, but rarely in economics or business. And it is remarkable how many of these students have said to me afterwards, “I expected this subject to be really boring, but it’s actually quite interesting!” I hope so. Learning to understand pricing will not only make you a more effective arts manager, but also give you insights into the various goods and services you buy for your household, such as groceries, or electronics, or vacation packages. At the very least, when a friend tells you about the pricing policies of some store and asks aloud, “Now why exactly would they do that?” you can surprise them with an answer.

Sources

The analogy of the billiard player is from Friedman (1953). A recent excellent, but very mathematically sophisticated, text on pricing is Shy (2008). Other surveys of strategic pricing, also forbidding to those without advanced training in mathematical economics, but from which I will draw some of the ideas presented in this book, are Tirole (1988) and Varian (1989). Less theoretical, but rigorous and with a dose of humor, is McAfee (2002).

![]()

2

PRELIMINARIES

This chapter introduces the key terms and the framework for analysis that will be applied throughout the rest of the book to our central problem of how to set prices. The key principle I want to introduce is that of considering marginal benefits and marginal costs in making decisions. I will illustrate this principle with a variety of scenarios to show the general applicability of the method across the spectrum of management problems, and we will then apply the method to pricing in all the chapters that follow.

Here is our first case: I teach at a university with a very distinguished school of music, full of dedicated students. Consider one student, Maggie, who is studying for a degree in piano performance. Outside of her lessons with her principal instructor, she has been practicing piano 25 hours per week. Should Maggie increase the number of hours to 26?

First, we need to know the marginal benefit of increasing the number of hours spent practicing. Marginal benefit is defined as the gains realized from increasing any activity by a small amount. In Maggie’s case, we need to know the gain from that additional hour; we don’t need to know the total value of her attending university or choosing to study music performance, we just need to know how much she would gain from that hour. The gains would come in various forms: she might feel greater personal satisfaction as her abilities improve; she might feel good about the increased respect she would receive from her teachers and peers; and she might see the extra practice as something that increases the number of opportunities for future performances. No two people are alike, and so there is no formula to which we can turn. But Maggie will have a sense of what the marginal benefits are to her, which is what matters.

We have been asking about the marginal benefit to Maggie from increasing the number of hours per week she practices from 25 to 26. But if she did adopt a new schedule of practicing 26 hours per week, we could then ask about the marginal benefit of a twenty-seventh hour per week, and a twenty-eighth, and so on. In general, we expect that for most things we do there are diminishing marginal benefits the more time we devote to any activity. If Maggie were to keep increasing the amount she practices each week, the gains she would receive from an additional hour would gradually fall; the extra practice time would have less and less impact on the quality of her performance. The notion of dim...