This is a test

- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

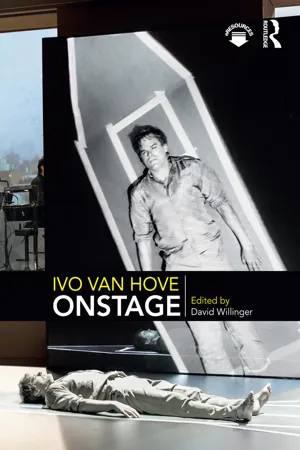

Ivo van Hove Onstage

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Since his emergence from the Flemish avant-garde movement of the 1980s, Ivo van Hove's directorial career has crossed international boundaries, challenging established notions of theatre-making. He has brought radical interpretations of the classics to America and organic acting technique to Europe.

Ivo van Hove Onstage is the first full English language study of one of theatre's most prominent iconoclasts. It presents a comprehensive, multifaceted account of van Hove's extraordinary work, including key productions, design innovations, his revolutionary approach to text and ambience, and his relationships with specific theatres and companies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ivo van Hove Onstage by David Willinger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre Direction & Production. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

van Hove, Virtuoso

Theatre is a sponge.

Ivo van Hove

The stage floor is a metaphor for all existence.

Jan Versweyveld

If the text doesn’t serve to make the spectator jump out of his seat, what good is it?

Bernard Crémieux

Introduction

It may be wondered why we choose this moment in particular to undertake a book-length study of this director, who, now in his fifties, still has much of his career ahead of him. Over the course of thirty-six years, Ivo van Hove has made a profound impact on the theatre life of several countries. Now, at the height of his powers, he is churning out productions at breakneck speed, including plays, operas, and hybrid musical works. He has become a major point of reference for theatre-makers, scholars, and aficionado audiences alike, much in the same way that Peter Brook made an impact in the 1960s, modeling a creative framework for an entire generation.

It is no exaggeration to assert that van Hove has come to a critical juncture. Precisely because his youth is decisively behind him, he can no longer lay claim to be a wunderkind and enfant terrible, labels which both haunted and catapulted his earlier career. And it appears that he has now decisively “gone to the next level” of acceptance and “arrival,” to have “crossed over,” if you will, in the major metropolises where he practices his craft on both sides of the Atlantic. Critics have conferred on him such august titles as: “the most important director in the theatre right now,” “one of the very few masters of European theatre,” “the most provocatively illuminating theatre director,” a “visionary director,” and a “revered director.” One blog breathlessly proclaims: “Ivo van Hove is God!”1 Formerly a star of the margins, an iconoclast who drew attention through controversial bold theatrical strokes that flew in the face of convention often at the risk of being shunned, he is now approaching a new equilibrium, a sort of enshrinement, where his ambiances, choices, and approaches would become a new institutional norm. “The strange, fascinating thing about van Hove,” says one critic, “why we keep lapping his work up for more effrontery—is that he styles himself as [both] a rebel and an establishment figure” (Gener 2009: 83).

In a real sense, he appears to have fulfilled a plan he had laid out for himself: “that’s my mission as a theatre director,” he once told an interviewer. “I want to make the most extreme work possible, without compromise, shown to as many people as possible.” This places him in a tradition together with van Hove’s heroes, Patrice Chéreau and Peter Stein, but most eloquently summed up in Antoine Vitez’ formula: “Elite theatre for all.”2 Van Hove has been featured in the Festival of Avignon and lauded in Paris. He has had long-running hits in London’s West End and has more in the works. His collaborations with mediatized stars, like Juliette Binoche, Phillip Glass, Jude Law, and David Bowie, have added further luster to the Flemish director’s “brand.” The list of honors bestowed on him is getting too long to include them all.3 One might say that a decisive leap from elitist highbrow for a select few cognoscenti to middlebrow for the general public, a move he has made no secret of desiring, is accomplished and ensured.

At this point, a critical one because it is so obviously littered with perils, possibilities, and temptations, it behooves us to look backwards to his obscure beginnings, take stock of his earliest aspirations and reception, and chart our way back to the crux at which van Hove now finds himself. Before he had emerged from the second-tier cultural capitals of Belgium and Holland and onto the world scene, he had already put a great deal of interesting work behind him. The present recognition of his talents will almost certainly elicit curiosity about these early shows. The ephemeral nature of theatrical art means that the chance to glean reasonably detailed impressions from that not so distant past is rapidly slipping away, and it is one of this book’s main purposes to fill in some of these critically important blanks. Having digested the large majority of his mise-en-scènes, we are faced with the difficult challenge of defining what inner and outer qualities epitomize the entire substance of this major director’s artistry—one so multifarious as to nearly traverse all boundaries.

Do we need to justify the notion that a theatre director is an artist in the same sense as and of equal interest to a playwright? It is true that far fewer books have been written about stage directors’ productions than about dramatists’ scripts. But a sea change has been taking place in the art of theatre since the advent of the modern theatrical director in the 1870s, when the Duke of Saxe-Meiningen and his hired hand, Chronegk, laid down a marker for this new profession with the innovation of process-oriented rehearsals and a steeply higher artistic standard for production values (Koller 1984: passim). It seems to me indisputable that pioneering theatre directors, no less than pioneering film directors, about whom there is perhaps less controversy, merit serious consideration as a discrete artistic category of creator and should not be written off as negligible interpreters. Notable film directors collaborate with camera people, editors, and other important creative contributors, yet are lionized as auteurs. Why would it be different for a theatre director whose special vision is recognized as determinant in what the audience gets to see?4

In a revitalized theatre in which scripts are mined for their visual and auditory life in unconventional ways, the thrall of the narrative is reduced. As images suggestive of states of being come to the fore instead, the directorial function assumes outsized proportions. Elinor Fuchs describes the current new prestige and parity that theatre workers beyond the playwright have attained, overturning the famous prescription that dramatic action is the most important of component elements:

In the theatre of difference, each signifying element—lights, visual design, music, etc., as well as plot and character elements—stands to some degree as an independent actor. It is as if all the Aristotelian elements of theater had survived, but had slipped the organizing structure of their former hierarchy.

(Fuchs 1996: 10)

With such a reconfigured hierarchy of Artistotelean elements, the director/designer, who after all is master of the formerly denigrated “spectacle,” gains a concomitant new prestige over Aristotle’s previously privileged element of dramatic “action,” which is historically the playwright’s domain.5 “The stage director,” as Rancière says, “is no longer the regent of the interregnum. He is the second creator who gives the work this full truth that manifests itself in becoming visible” (Rancière 2011: 125). I trust that the discussion which follows will be a self-justifying one, speaking to “respect for directing” when it comes to an innovator such as Ivo van Hove.

For want of a common, rigorous vocabulary for describing theatre directing as an art, I will be borrowing from others and, in certain cases, introducing terms of my own as they become necessary, trusting that this approach will be comprehensible to all. In framing the discussion of van Hove, I will have recourse to certain influential, already canonical, modern performance theoreticians—Elinor Fuchs, David Savran, Hans-Thies Lehmann, and others—whose works all appear to me germane to the discussion and were written roughly over the time period through which van Hove’s efflorescence has taken place. Underpinning all I write are also the ideas and vocabulary of older, today seldom referenced theoreticians—Susanne Langer and Bernard Beckerman. That does not imply, however, that van Hove himself has absorbed or has been responding to any of these particular writers’ commentaries in his productions. It is certain that he hasn’t; it will be shown that his reading interests lead him elsewhere. The truth regarding van Hove, if not for many of his European brethren, is as Fuchs suggests that “postmodern theater practice … takes little interest in theoretical debate, just as the theoreticians are less aware of actual theater than of any other art” (Fuchs 1996: 95; Pavis 2003: 26). And yet, certain of his artistic statements—and especially his practice—coincide marvelously with elements of their theories.

Progression and patterns

Van Hove’s first two shows were plays he wrote himself. Rumors (1981) was his first production and it showcased four performances in the setting of a disused laundromat (see Figure 1.1). He wrote and directed it, with Jan Versweyveld designing all elements of the show:

Through a theatrical structure that is not narrative but imagistic and poetic we are presented with subjective fragments of the life experience of a young man become schizophrenic. The ensemble of decimated architecture; mobile, multi-colored fluorescent lights (designed by Jan Versweyveld); abrasive sound-track of words and music; ambivalent text and acting all suggest the inner world of the schizophrenic’s mind spatially and sonorously.

(Willinger 1981: 116–118)

So many elements contained the seeds for things that returned in more polished forms in later shows: the precarious theatricality of the set, the semiotics of the lighting, the use of an “elect performer” whose silent gaze leads the audience’s interpretations (like the maid characters in Hedda Gabler and Things That Pass), the uncanny framing of the lower halves of the bodies (which we see again much later in Ludwig and Edward II in mediatized versions), the film-stage ambiance, which pops up again in The Antonioni Project and Opening Night, the figure of the inarticulate outsider hero trying to find himself, and so on.

Figure 1.1 Rumors

© Chris Van der Burght

I would also say that the text stands up despite its fragmentary nature. It is still one of the best pieces of dramatic writing to come out of modern-day Flanders. Van Hove emerged from the Rumors experience confident of his directorial abilities. Not so for writing. He later said that he resolved to leave writing to others as he didn’t have the knack, but that playwriting, along with singing in a rock band, remains one of his unrequited ambitions (Willinger 2014). I’ve never heard him sing, so I can’t weigh in on his assessment on that front, but I do regret the plays he never wrote, owing to lack of confidence.

Van Hove’s second play, Disease Germs, is like some camp grand opera, in which the uniformly female cast of characters is played by men (see Figure 1.2). In sensibility, Disease Germs is not so very different from the Genet of The Maids or Werner Fassbinder’s hysterical operatic film The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant.

And by operatic, I intend a very particular connotation. There is no explicit singing (in fact all the musical selections are borrowed paradigms of recorded kitsch: James Bond soundtracks, Citizen Kane, The Merry Widow, etc.), but the characters bemoan their fate through operatic postures, by way of spoken arias and duets. There is something Wagnerian about the feverish emotional tone of these set pieces, so that all genuine feeling gets expanded in the crucibles of operatic convention and cliché.

Figure 1.2 Disease Germs

© Leo Peeters (Keoon)

Looking back from this point in time, it is clear that in Disease Germs van Hove and Versweyveld were laying down certain markers that have recurred in new iterations throughout their extensive oeuvre: the insertion of kitsch pop songs and tunes, the masterful use of spatial planes and shuttering off of parts of the space, from the Typist’s office at the furthest remove down to the intimate closing scenes with Jeanne and Joanne, the emphasis on physical and visual action, the addition of stunning visual treats—in this case, a real, working automobile—and the tropes of gender exploration. In these earliest shows, there is a blatant, cruel humor, which is hard to detect in most of the later work, but which is great fun.

After some time, it became apparent that van Hove was not going to be a theatre director in the mold of Richard Foreman or Tadeusz Kantor; one who would mine a single signature vein of style and process throughout a long career. Neither did he go through one stylistic or thematic period, then leave it behind forever to start a new one, forging coherent, neatly defined periods. A look at his chronology confounds all efforts to compartmentalize his career into phases of literary interest, theme, or style. Rather, his trajectory resembles that of Patrice Chéreau, the notable French director he admired, who juggled a varied, but definite set of interests and tendencies.

In his first decade of directorial activity, van Hove established many of the threads he would follow in the future, leapfrogging over one to another. In his earliest two productions, Rumors and Disease Germs, he shook up the audience by inviting them to derelict and gutted industrial spaces. Having introduced this use of site specificity, he dropped it and went on to other challenges. Thus, he eludes any easy labeling—in this case, being branded as a director of the site specific. But lo and behold, thirty years later, he exploits a disused cavernous warehouse on Governor’s Island in New York harbor for his American production of Teorema. He is both faithful and unfaithful to his experiments.

For van Hove is an oscillator: one who oscillates between fulfilling the role of standard director of European repertory theatre introducing moderately unusual choices (The Russians, South, Lulu) and unleashing his auteur instinct (Faces, Cries and Whispers, Roman Tragedies) to stage break-ins on our comfort zone; he also oscillates between scandal and respectability, between competence and transcendence, between gay and straight tropes, between being a pioneer of sound, silence, and image theatre and explicator of text theatre. His stages may be empty or cluttered. He is both an avatar of high art and an unabashed purveyor of pop kitsch; works with tech-centered theatre and organic theatre of the human body. He is both mercurial and faithful, bull-headed and equivocal. He wants to borrow and adapt, embark on the unknown and nestle down into the safe modes of expression too. In the beginning, his work burst out with youthful impetuosity and, frequently, rage. Now, the two energy batteries of impetuosity and mastery, pump in alternation and often intertwine.

With the succinct self-observation: “I’m a bungee jumper of the theatre” (Szalwinska 2011). Van Hove acknowledges ownership of this far-ranging, if erratic, pattern. Elaborating on the multiple modalities of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Selected chronology

- Abbreviations

- 1 van Hove, virtuoso

- 2 From Mourning Becomes Electra to Long Day’s Journey into Night: Ivo van Hove directs Eugene O’Neill

- 3 Ivo van Hove’s cinema onstage: reconstructing the creative process

- 4 Love still is love even when it lacks harmony: Antigone and the attempt to humanize tragedy

- 5 Reality overtakes myth: Ivo van Hove stages Der Ring Des Nibelungen

- 6 Kings of War or the play of power

- Appendix 1: Roman Tragedies

- Appendix 2: Interview with Ivo van Hove by Johan Reyniers

- Index