This is a test

- 640 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Written in an easy-to-read, narrative format, this volume provides the most comprehensive coverage of North American Indians from earliest evidence through 1990. It shows Indians as "a people with history" and not as primitives, covering current ideological issues and political situations including treaty rights, sovereignty, and repatriation. A must-read for anyone interested in North American Indian history.

This is a comprehensive and thought-provoking approach to the history of the native peoples of North America (including Mexico and Canada) and their civilizations.For Native American courses taught in anthropology, history and Native American Studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access North American Indians by Alice Beck Kehoe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

America’s Earliest Humans

The peoples known as American Indians are descendants of the original human inhabitants of the American continents. They are the First Nations, by international law the discoverers of America and sovereigns of its lands. As happened over and over on the other continents, foreign invasions massively disrupted most of the American First Nations, bringing famine and disease to augment slaughter. Although a few of the First Nations have disappeared, the majority survived conquerors’ onslaughts. Today’s American First Nations assert their lawful rights to their homelands and meld their distinctive heritages with the opportunities of twenty-first-century life.

Evidence now available, drawn from the fields of geology, biology, and archaeology, indicates that hunters began moving through the Americas some fourteen thousand years ago, very possibly earlier. Small bands of people continued shifting eastwards and south from the northern continent while earlier settlers increased in population, until by A.D. 1492 there may have been close to fifty million people in North America, from the Inuit (Eskimo) families ranging the Arctic Ocean to the populous nations of Mexico.

Section 1: Earliest Americans

Archaeologists argue over when the first humans came into the Americas. A radical view is that there have been humans in North America for maybe one hundred thousand years. Proponents of this extreme position argue that there were probably more periods during which the sea level was low enough that today’s narrow, shallow channel between Asia and Alaska, the Bering Strait, was above water and there was a single land mass encompassing the present two continents. The principal problem in accepting the radical view is that there is no evidence of humans in what is now northeastern Siberia before approximately 33,000 years ago (as evidenced at the Dyuktai site there). It is true that most of northeastern Asia is poorly explored

Conflict of Opinion on the Origin of Native American Populations

Philosophers point out that there are many “universes of discourse.” In each, certain ideas and facts are considered to be relevant, others irrelevant. Each universe of discourse includes basic presuppositions that are taken for granted. Arguments between persons of differing views often arise from disagreement over the acceptability of these fundamental assumptions.

Two often conflicting universes of discourse are science and spirituality. Science is concerned with the testing of information gathered through observation of the phenomena of the natural world. Spirituality is concerned with the search for the ultimate, transcending reality, which includes but need not be limited to the observable natural world. Scientists will not admit as a presupposition that final truths have already been grasped by human minds; in spiritual discourse, it is accepted as an axiom that humans can and perhaps have received the revelation of ultimate truth.

The origin of American Indians is a subject of scientific discourse and also one of personal concern to American First Nations. The latter may bring to their discourse a conviction that American Indians are markedly different from all transoceanic peoples. This may seem so obvious to persons who have grown up within Indian societies that it is accepted without question. The implication of this presupposition is that American Indians evolved in North America independently of any connection with humans on other continents. Lack of evidence of protohumans in America is then interpreted to indicate there has been insufficient exploration for such ancient remains in the Americas.

Scientists do not accept this presupposition of differences, but instead examine evidence pro and con. The weight of evidence seems to indicate, to scientists, that the remote ancestors of American Indians were part of the human population of what is now eastern Asia, who moved into present-day America thousands of years ago. This hypothesis accounts for the many biological similarities between American Indians and other peoples, and for the lesser number of biological differences (chiefly a more narrow range of genetic variations, compared with the total range of genes found among humans in the world as a whole). The hypothesis is compatible with more general hypotheses of biological evolution and population growth and change.

The basic disagreement lies in the evaluation of legendary histories. Belief that such a traditional history recounts final truths revealed to seers in the past rests upon a presupposition outside the scientific universe of discourse. Most scientists and laypersons resolve apparent contradictions between these universes by understanding that spiritual discourses refer to a universe greater than the material world, one that our human languages can describe only poorly and that most of us can at best only glimpse. Accounts of the beginnings of the world may use allegory and parable to convey moral principles. We separate our scientific explanations of observable data from our deeper convictions of ultimate truth.

This book lies within the anthropologists’ universe of discourse. It is a mundane universe without claim to final knowledge of transcendent reality. On the question of the origin of American Indians, as on other issues within the spiritual as well as the scientific universe, the text seeks only to present and interpret the data at hand. Readers looking for explanations derived from legendary revelation must turn to books discoursing on the spiritual universe.

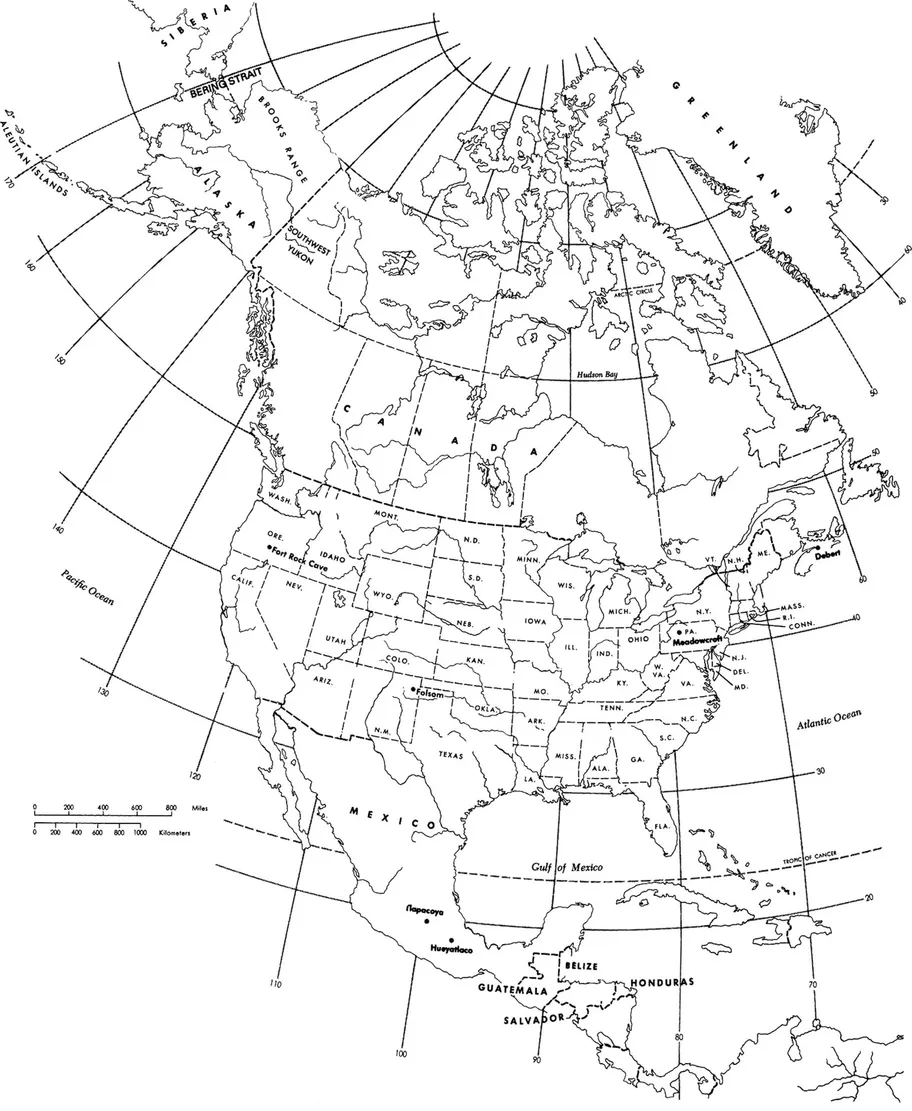

FIGURE 1.1 America’s earliest humans

Background on Human Evolution

The first mammals appeared some two hundred million years ago. For an extremely long period, mammals lived among and competed with dinosaurs, many of which, it is now believed, were warm-blooded like mammals and unlike reptiles. The principal difference between mammals and the later dinosaurs may have been that female mammals carried their developing young within their body and nourished them with milk after birth, whereas the female dinosaurs laid eggs and fed the hatched young with regurgitated food.

Approximately seventy million years ago, forces within the earth began to break up land masses. Changes in climate ensued as continents slowly moved from one latitude to another, and as the pressures of continental masses drifting against each other forced up mountains. A meteor crashing into Earth raised enormous clouds of debris and fumes that killed vegetation and masses of animals. Mammals, generally smaller than the dinosaurs that perished, were apparently better able to adapt to changed conditions, in part because they provided better care for their young, perhaps in part because, being smaller, they required less food. Mammals not only survived but, freed from competition with dinosaurs, spread through many ecological niches (habitats) formerly dominated by the dinosaurs.

Among little mammals of the period of early continental drift were rodentlike creatures that ran along tree branches catching insects. Their ecological niche, the lower branches of tropical forests, was rich in food, comfortable, and relatively free from competition from other types of animals, higher-flying birds and rodents on the ground. Tree-dwelling, insect-catching mammals consequently prospered, and mutants able to survive in specialized habitats or more efficient in utilizing the resources of the tropical forests became founders of new species. Several species of these prosimians (Latin for “before apes”) can be recognized among the fossils from tropical regions of sixty million years ago. (Many prosimians survive to the present. They include lemurs you can see at zoos.)

A few million years later, monkeys had evolved. Monkeys differ from prosimians in having better developed vision, more finely coordinated fingers (and toes), and, most important, greater intelligence. These advantages allowed the monkeys to dominate when in competition with prosimians within their habitats. Many prosimians became extinct. During this period, South America drifted wholly apart from other continents (including North America). Primitive monkeys in South America flourished in their tropical forests, but no radically different new forms of primates (monkeys, apes, humans) appeared in the relatively stable environment of the South American tropics.

Eurasian (Europe and Asia are one continental mass) and African tropics presented quite a different picture. By twenty-eight million years ago, a variety of monkeys were competing with apes, primates having even larger brains. From then until the present, evolution tended to give this stock both greater intelligence and greater body size, which established for apes a secure place in tropical habitats. By two million years ago, natural selection within tropical forest margins and grasslands produced from the primates the immediate ancestors of true humans. This type of primate had a larger brain than any ape or monkey; it stood and ran upright, freeing its hands for carrying things; it was accustomed to making tools to better perform tasks; and it was developing well-coordinated social groups whose members regularly helped one another.

Until nearly a million years ago, humans were restricted to their ancestral tropics and temperate zones. Then, some extraordinarily courageous and inventive persons discovered how to tame fire. The control of fire enabled humans to live in colder regions, and much of the world was thereby opened up to immigration. Campfire by campfire, bands of people advanced into northern China, Siberia, and eventually into North America, a continent with no other primates, and South America, where primitive monkeys were the sole representatives of this ancient order of mammals.

Continental drift had separated the Americas from the other continents before the mutations that eventually gave rise to the human species appeared. Scientists consider all American peoples descended from ancestors ultimately from Eurasia and Africa.

archaeologically, but there have been several well-carried-out Russian investigations into the prehistory of eastern Siberia and a great deal of recent work by Japanese archaeologists in their homeland, which was once part of mainland Asia. Russian, Japanese, Korean, and American archaeologists are now collaborating in conferences and in the field. Both the Russian and Japanese researchers suggest that Asia north of the temperate latitudes was not colonized by humans until the fully modern physical type (Homo sapiens sapiens) had evolved and had developed the complex technology of the Upper Paleolithic period (approximately 35,000 B.C.–8500 B.C.). The premodern humans (Homo erectus) and the protomodern humans (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, or Neanderthal) have not been found beyond southern Siberia and northern China, the edge of the temperate zone.

The radicals base much of their claim for the great antiquity of humans in America upon a site in southern California called Calico Mountain. The site is an alluvial fan (a deposit of soil and gravel washed down from a hillside) in the California desert. On and in this deposit are crudely broken sharp-edged rocks and scattered concentrations of bits of charcoal. Those who believe the site represents human occupation one hundred thousand or more years ago think the rocks are the stone tools of Homo erectus and charcoal from their hearths. Those who do not accept this claim of great antiquity for Calico Mountain are convinced that some of the rocks were naturally fractured while rolling in the flash floods that contributed gravel to the alluvial fan, and that other rocks were quickly made tools abandoned by Indians hunting in the region in the relatively recent past. The charcoal concentrations are said to be the remains of creosote bushes flamed by lightning. The unprejudiced archaeologist is most disturbed by the unstable nature of the alluvial fan, in which the rocks could have been naturally shifted from their original positions, and by the consequent lack of secure association between the alleged tools (artifacts) and means of dating them, such as charcoal bits or geological layering.

There are a number of other finds of crude stone artifacts that suffer from problems similar to those of the Calico Mountain site. The artifacts lie on or near the surface on fans or hillside terraces that may in themselves have been formed many thousands of years ago, but that have been available for camping right up to the present. Crudity alone does not indicate antiquity for a stone tool, since most people—including you, reader—have sometimes picked up a handy stone to break or hammer something, then discarded the stone after use. Only if the artifact lies buried under undisturbed layers of soil, and is closely associated with similarly undisturbed means of dating, can antiquity be accepted.

Archaeologists seeking evidence of early humans in Alaska and the Yukon in Canada encounter problems similar to those of the Calico Mountain investigators. Logically, the oldest evidence of humans in the Americas should be in Alaska and the Yukon because in the late Pleistocene Ice Age, this northwestern section of present-day America was more than once part of the northern continent including Siberia. During the coldest phases of the Pleistocene, so much water was frozen in the huge glaciers that sea level was lower than today, and the shallow Bering Strait between what we know as Siberia and Alaska was dry land, called Beringia by geologists.

Animals moved east and west over Beringia, and human hunting bands could have followed over the cold plains of tundra, grass and sage, and occasional forest. Mammoths, giant bison, caribou, elk, wild sheep, and horses grazed the Beringian plains. Searching the gravelly outwashes of Yukon rivers, archaeologists have picked up dozens of chunks of mammoth bone that look as if they had been chipped like flint into sharp-edged flakes. Evidence for Beringian humans substituting massive mammoth bone for scarce stone in making artifacts? Or natural breakage of the bone by trampling mammoths or in raging floods? To test one possibility, archaeologists threw an elephant bone into a cage of elephants to see whether their trampling would break it up into pieces like the Beringian chunks. It didn’t, but the single experiment isn’t a final answer. We do know that humans butchered mammoths in the Yukon, at Bluefish Cave, but the radiocarbon date of 13,500 B.C. doesn’t directly date the artifacts, and interior Alaska sites, known as Nenana type, date only to 10,000 B.C. Nenana artifacts resemble those found in some northeastern Siberian sites dated around 12,000 B.C.

Most archaeologists assume that the spread of Upper Paleolithic peoples throughout northeastern Asia brought the most far-ranging bands comparatively quickly (within a few thousand years) through Beringia into North America. They might have come even during periods of higher sea level, since the Bering Strait is only fifty-six miles (ninety kilometers) wide. A couple of small islands rising from the middle of the Strait make small boat crossings easier, and in winter, when the shallow Strait freezes, people could walk over on ice. In clear weather, the far mainland can be seen from the coasts.

Forests may have been a worse barrier than the Bering Strait. Forests have a low density of game compared to grassy plains, and forests were probably extensive in both Siberia and America from about 60,000 to 23,000 B.C., when increasing cold led to the last major glaciation, about 20,000 to 12,500 B.C. During this last glaciation, mountain valleys and great regions of northern America and Asia were closed off by glaciers, but there were always areas of Beringia open to game and to humans, so no span of time can be ruled out for human migration.

What frustrates archaeologists is that much of that part of Beringia most favorable to human living is now below the sea. Historically, human populations in the Arctic have been most dense along the seacoasts where sea mammals such as seals, sea birds, fish, and shellfish provide food that can be supplemented by land game such as caribou and by river fish. The only remnant of the ancient Beringian coast preserved today and available for archaeological investigation is the Aleutian Islands. Excavated villages in the Aleutians have been dated back to around 4000 B.C.; perhaps earlier settlements were closer to the lower coastline of their time, and have since been flooded by rising sea level. Underwater archaeology has been attempted off our present coasts, but it seems to work reasonably well only for salvaging historic ships: ancient sites lie under so much mud they can’t be found.

That humans migrated south and southeastward from Beringia into America before or during the last glacial maximum is suggested by a number of finds in Central and South America. It is reasonably certain that people were living at the far tip of South America, Patagonia, by 10,000 B.C. In south-central Chile, Tom Dillehay excavated butchered mastodon (an extinct elephant adapted to temperate climates) and bits of wooden artifacts and house structures, radiocarbon dated to 12,000 B.C., in a site called Monte Verde. Possible crude stone tools and charred wood were uncovered in a lower, older stratum at the site. Richard S. MacNeish recovered bones of extinct sloth and horse with crudely chipped stones that might be tools in Pikimachay (Flea Cave) near Ayacucho in the highlands of south-central Peru, where the lowest, oldest occupation layer is dated to 12,000 B.C. Niéde Guidon, an archaeologist experienced in French Paleolithic sites, exposed a series of occupation layers with stone artifacts in Pedra Furada, a rockshelter in northeastern Brazil; radiocarbon dates indicate some layers may be from 30,000 B.C., but whether any artifacts are that old is much debated. Pedra Furada does have rock art, little red-painted figures, dated to 12,000 B.C.

Sites in Mexico and the United States give support, but not absolute proof, for the liberal estimate of the time depth of human residence in the Americas. Hueyatlaco in the Valsequillo region southeast of the Valley of Mexico contained what appear to be butchered bones of horse, of a llama-like American camel, and of mastodon, as well as stone artifacts. These lay in ancient stream gravels rather than in a stable soil “floor” of a camp, so they have been difficult to date, although a geologist’s estimate of 20,000 B.C. for the time the gravels were laid down does not seem unreasonable. Tlapacoya in the Valley of Mexico, in modern Mexico City, has what looks like a briefly used camp, with a couple of small flakes of chipped stone and a possible hearth, and a man’s skull radiocarbon dated to 10,000 B.C.; a woman’s skeleton uncovered in Mexico City, “Peñon Woman,” dated even earlier, 10,750 B.C. Meadowcroft Rockshelter in western Pennsylvania near Pittsburgh has its lowest human occupation layer dated to 12,500 B.C. Meadowcroft’s archaeo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 AMERICA'S EARLIEST HUMANS

- 2 THE RISE OF THE MEXICAN NATIONS

- 3 THE GREATER SOUTHWEST

- 4 THE SOUTHEAST

- 5 THE NORTHEAST

- 6 THE PRAIRIE-PLAINS

- 7 THE INTERMONTANE WEST AND CALIFORNIA

- 8 THE NORTHWEST COAST

- 9 THE ARCTIC AND SUBARCTIC

- 10 FIRST NATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA IN THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD

- APPENDIX: ANTHROPOLOGY AND AMERICAN INDIANS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- CREDITS

- INDEX