eBook - ePub

Sustainable Solutions

Developing Products and Services for the Future

- 469 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Toughening environmental legislation, national and supra-national environmental product policies and growing customer demands are focusing the attention of companies on the environmental and broader social issues linked to the creation and delivery of their products and services. There is now an urgent need for appropriate management structures, practical tools and increased awareness among all stakeholders in the product development process and throughout the entire product life-cycle. These are huge issues – with major implications for corporate management, design and production strategies. Sustainable Solutions provides state-of-the-art analysis and case studies on why and how cutting-edge companies are developing new products and services to fit "triple-bottom-line" expectations. The book is split into three sections: first, the broad issues of business sustainability are examined with focus on sustainable production and consumption and consideration of North–South issues. Second, the book tackles the major methodologies and approaches toward organising and developing more sustainable products and services. Third, an outstanding collection of global case studies highlights the progress made by a wide range of companies toward dematerialisation, eco-innovation and design for durability. Finally, the book collects together a comprehensive list of web addresses of useful organisations. Practical and comprehensive, Sustainable Solutions will be essential reading for corporate managers, product designers, R&D staff, academics and all individuals interested in a definitive source on how new product and service development can and is contributing toward tacking the challenge of sustainable development.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Background to Sustainable Consumption and Production

1

Sustainable Development

From catchwords to benchmarks and operational concepts

Joachim H. Spangenberg

Sustainable Europe Research Institute, Germany

Sustainable Europe Research Institute, Germany

The terms ‘sustainable development’ and ‘sustainable consumption and production’ are used by different actors with diverging definitions and sometimes biased interpretations. For the sake of clarity, the historical development of the concept is briefly summarised (Section 1.1), before a number of frequently used definitions and measurements on the macro level are described (Sections 1.2.1 and 1.2.2). Then a macro-level concept is presented, including sustainable production and consumption and links to the micro level (Section 1.3). Finally, the barriers to political implementation and some key issues for ecodesign are introduced (Section 1.4).

1.1 The history of development of the sustainability concept

The term ‘sustainable development’ was first introduced into the international policy debate by the World Conservation Strategy (IUCN/UNEP/WWF 1980). It became established as a new global paradigm only after Our Common Future, the final report of the Brundtland Commission, had been published (WCED 1987) and the preparatory work for the United Nations (UN) Earth Summit 1992 had begun.

However, despite all the attention devoted to the concept, the perception of its core message regarding the integration of environment and development remained ambiguous. In the North sustainable development was predominantly understood as one more new environmental concept, like environmental modernisation, greening the industrial metabolism or safeguarding biodiversity as the common heritage of humankind had been beforehand. In much of the South, however, the term ‘sustainable development’ was taken as meaning poverty alleviation and economic development. These diverging perceptions are not only the result of differing priorities, but are also the result of controversial interpretations of environmental problems arising since the early 1970s.

During the 1970s, Limits to Growth, the report to the Club of Rome (Meadows 1972), was shaping the debate in the North, stressing the need to change the current development path in order to maintain a safe resource base for human societies. In the US, this contributed to the perception of population growth as the main future risk, whereas in Europe the focus was more on individual and industrial consumption patterns (strengthened by the subsequent oil price crisis). The South, however, understood the argument as an attempt to deny the ‘right to development’ they had been promised (e.g. in the Human Rights Charter). Regarding resource consumption, they saw the challenge not in terms of ‘limits to growth’ but in a fair distribution of wealth: according to Mahatma Gandhi the world has enough for everyone’s need, but not for some people’s greed. This position was most clearly stated in Limits to Misery, a report in response to Limits to Growth and produced on behalf of the Bariloche Foundation, Argentina (Herrera and Skolnik 1976). It resurfaced in the sustainability discussions in the late 1980s and led to the statement in Agenda 21 that the ‘excessive demands and unsustainable lifestyles among the richer . . . place immense stress on the environment’ (UN 1993: 31).

One of the key objectives of the Brundtland Commission was to reconcile these two positions. It tried to do so by updating the environmental dimension by focusing on global environmental systems and their absorptive and carrying capacities and by embarking on a globalist view concentrating on the interdependencies of North and South. It highlighted their shared responsibilities, without ignoring the factual inequality in power, influence and responsibility. The Commission succeeded in avoiding much of the polarisation of the 1970s by organising the debate around the term ‘sustainable development’, which by its very definition ruled out trade-offs between environment and development, leaving only the question how to create the win–win situations envisaged.

The problems encountered in the process of developing a broadly shared view became even more obvious in the preparatory phase of the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UN 1993). Officially it was a consensus-oriented discourse about the best solution for the world’s problems. Politically, it was a power battle. On one side there was the extreme version of neoliberal deregulation politics (represented by the US government, members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries [OPEC] and major businesses). Their opponents followed an ordo-liberal1 responsible capitalism approach including social and environmental standards represented by social-democratic leaders from Latin America and Europe as well as by the US Democrats (Roddick 1998). Nevertheless, the compromise reached in the end was praised globally for its landmark quality, but it necessarily meant sacrificing some goals for all parties involved. Rio 1992 was a kind of watershed: whereas before environmental issues had been shaping the public discourse in many parts of the world for some time, soon afterwards the globalisation and deregulation discourse began to dominate. This change also resulted in a certain reluctance regarding the implementation of the UNCED decisions, in particular from those who felt that the current balance of power was more favourable to them than the results obtained in 1992.

1.2 What is sustainable development?

Given the underlying conflicts, the unanimous agreements of Rio de Janeiro 1992 and, before that, the consensus of the Brundtland Commission are all the more remarkable. It is thus most plausible to start elaborating on the meaning of sustainable development by unfolding the description given by the World Commission for Environment and Development (WCED).

1.2.1 Sustainable development: a definition

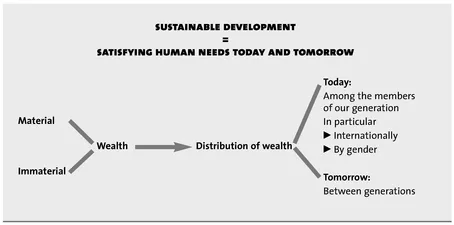

The WCED has given the most frequently quoted criterion for sustainable development by characterising it as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED 1987: 43). This statement is as close to a definition of sustainable development as the Brundtland Commission has come but it is frequently considered as being too vague to provide any operational value. Nonetheless, it immediately illustrates that sustainability is not environmentalism dressed up for the new millennium but is essentially a new way of seeing the world (see Fig. 1.1), based on considerations of intergenerational and intragenerational justice and shared responsibility.

Human needs (not only material ones!) should be met and the opportunity to lead a dignified life should be granted not only to specific groups but also to the population at large. This criterion calls for an equitable sharing not only of the benefits of the consumer society but also of the risks it immanently produces (Beck 1986). It provides an interesting point of departure for ecodesign, because, obviously, contributions to sustainability cannot be limited to marketable products but need to start from human needs and to look for the most sustainable ways to satisfy them. This can be achieved by products, by eco-efficient services or even by social processes. Furthermore, accessibility and affordability even beyond pure market concerns become important criteria for ecodesign.

For future generations, the opportunity to meet their own, self-defined needs (probably differing from those of the current generation) has to be assured. This criterion requires freedom of choice to be granted to generations to come. It includes the preservation of nature and its resources in such a way that future generations will still find a sufficient basis for their preferred lifestyles, based on possibly different value systems.

Based on this understanding of sustainability, measurements have been developed. Since criteria such as ecosystem resilience, poverty and income distribution are defined on the macro level, they are macro measures. Only after such a macro measure has been agreed can the micro effects influencing be explored, be it in terms of household consumption (Section 1.3) or entrepreneurial activities.

Figure 1.1 The goal: sustainable development

1.2.2 Macro measurements

Grounded on these core elements of sustainability, a number of attempts have been made to assess quantitatively the sustainability of a given development path (for an overview, see Guinomet 1999), based on the conceptual bases provided by different disciplines and sub-disciplines.

On the one hand physical data has been aggregated to derive quantitative indicators or even indices of sustainability. These tend to describe the input of the ‘industrial metabolism’ (Ayres and Simonis 1994) in terms of energy and material flows from a resource economics perspective. The output is predominantly treated according to toxicological and ecological criteria, including an analysis of the state of the respective environmental systems (e.g. Eurostat 1999; for an overview, see Walz et al. 1995). Many of the methodologies suggested suffer from the fact that, because of the diverging geographical outreach of different environmental problems, the indicators derived also apply to different geographical scopes, rendering them quite problematic as a basis for political decision-making. One way to overcome this problem is to develop rough measures such as the ‘ecological footprint’ (Rees and Wackernagel 1994) or the sustainable process index (SPI; Eder and Narodoslawski 1999), both based on land-use analysis, or the ‘ecological rucksack’ (Schmidt-Bleek 1994), based on material flow accounting. For energy, a number of measures have been developed: for example, emergy accounting (Odum 1996), exergy measures (Ayres et al. 1996) or embodied energy analysis (King and Slesser 1994). All of these suffer from the fact that land, material and energy have no common denominator, so a combination of these three numeraires as included in the environmental space concept (Spangenberg 1995; Weterings and Opschoor 1992) provides less biased and more comprehensive information. Furthermore, environmental space combines the definition of a maximum threshold for resource use, derived from carrying capacity analysis, with a socially defined minimum criterion for access to resources as a core element of sustainable development.

On the other hand, monetary valuation of environmental assets and damages and, in some studies, of social achievements as well, is suggested (for an overview, see van Dieren 1995). This can be done within the framework of national accounting systems (Bartelmus 1999) as an attempt to derive an environmentally adjusted gross domestic product (or only partially monetarised in the system of integrated environmental and economic accounting [SEEA]). Other options are to calculate the damage cost in monetary terms, based on a valuation of the damage to humans, goods and the environment, but there are severe difficulties in particular in assessing future damage potentials. The same holds true for avoidance cost calculations, which not only need a comprehensive analysis of the damages caused but also a reliable estimate of the potential cost invoked by avoiding the damage. This is not easy for damages already detectable, and it becomes all the more challenging when future damages as well as future technologies and their respective cost are concerned. Most approaches concentrate on the valuation of environmental damages, with little attention paid to the social impacts.

Another economic approach does not focus on the damages but starts from the notion of capital stocks (Pearce et al. 1990). In this approach, the capital stock of the economy (assets, equipment, infrastructure) is called ‘man-made capital’, the stock of environmental resources (sometimes extended to functions such as the atmospheric sink capacity for carbon dioxide [CO2]) constitutes ‘natural capital’, and the personal skills of people are termed ‘human capital’. Few studies recognise the value of institutions, i.e. interpersonal structures such as norms, laws and organisations (the social capital) for sustainability as well as for the economic process (World Bank 1997).

According to economic theory, non-declining capital stocks can provide a long-term reliable income. Consequently, a sustainable income can be achieved by not depleting the stock, which implies limits to the maximum extracti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- PART 1: Background to Sustainable Consumption and Production

- PART 2: Sustainable, Eco-product and Eco-service Development

- PART 3: Case studies

- Useful websites

- Bibliography

- List of Abbreviations

- Author Biographies

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sustainable Solutions by Martin Charter,Ursula Tischner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.